Marketing Gut Health

Consumers want foods that aid gut health, but brands face a major challenge. How can they educate buyers about microbiome health benefits without getting into trouble with regulators?

“It’s no longer enough to just say ‘healthy,’” says Alon Chen, CEO and co-founder of Tastewise, an “AI platform for food brands.” “We are absolutely more critical of health claims in general. We want to know how, we want to know why and we want it backed by science.”

The term “healthy” is no longer resonating with consumers. Over 30% are looking for products with multifunctional benefits, according to research by Tastewise. They want more detail, on topics such as gut health, sleep improvement, brain function, anti-bloating and energy.

“Food is no longer just about nutrition, nor is it about general health,” says Flora Southey, editor at Food Navigator. “Consumers want more from the food they consume – and they want to be specific about it.”

What are the challenges and opportunities for brands trying to deliver gut health? A panel of food and nutrition experts tackled the issue during a Food Navigator webinar: “From Fermentation to Fortification: How is Industry Supporting Gut Health and Immunity?” Here are highlights.

Regulation Woes

There are trillions of microbes in our gut, but science has only scratched the surface of their power. Gut health is an ambiguous – and often confusing – subject for consumers.

Regulations on gut health claims are evolving. A year ago, the European Food Standard Authority asked food producers to help evaluate microbiome-based product claims.

“In order for us to assert ourselves in the industry, we have to be able to defend and support these claims,” says Anthony Finbow, CEO of Eagle Genomics, a software company incorporating microbiome research into their data analysis.

It’s “the dawn of a new age,” according to Finbow. Major food companies are now valued for delivering nutrition in addition to caloric content. “There is greater consumer understanding that food is a mechanism for better health.”

Southey feels brands need to do more for consumer education “I’m not convinced [the message is] getting to the consumer as well as it should be.”

Nutrition drink brand MOJU is attempting to tackle the regulatory stumbling block of health benefits on a label. Strict rules requiring detailed substantiation have resulted in few gut health claims“We’ve got a long way to go from an education point of view,” says Ross Austen, research and nutrition lead at MOJU.

MOJU can’t use the term “gut health,” but they can say a drink contains vitamin C or D, which have been proven to boost the immune system. They can’t say their drink is anti-inflammatory, but they can say it contains turmeric, known for its anti-inflammatory properties.

Marketing -Biotics

More consumers want the presumed gut health benefits of probiotics, prebiotics and postbiotics to power their microbiome. Probiotics “have largely stolen the headlines over the past few years,” Austen says, but prebiotics are appearing in more and more products. MOJU puts prebiotic fiber in their drinks because probiotics are a challenge for packaged food products. Because probiotics contain live and active cultures, they must be refrigerated and their efficacy tested.

Ashok Dubey, Phd, senior scientist and lead for nutrition sciences at TATA Chemicals (a supplier of chemical ingredients to food and drink producers), agrees. Dubey feels that the benefits of probiotics have been diminished in the minds of consumers. He notes that when probiotics first began appearing in foods 20 years ago, they were claimed to be able to solve any and all health ailments.

“There’s a greater understanding that our gut microbiota is so complex, if the food we eat is so complex, then the solution we should provide should be a combination of all of this,” he says. Dubey is seeing more patents combining probiotics and prebiotics, a complex solution that he says looks at whole health.

But, he notes, any claim with -biotics must be validated by scientific research.

Traditional Foods vs. Clinical Trials

Hannah Crum, president of Kombucha Brewers International (KBI), takes issue with the need to validate every health claim with scientific research. “We shouldn’t displace a huge body of traditional knowledge in favor of pharmaceuticals,” she says.

Making health claims around -biotics has been challenging for the kombucha industry. “It doesn’t honor what food does for us nutritionally,” she adds. Today’s food industry is so heavily regulated that foods traditionally consumed by humans for centuries – like kombucha – can’t put a health claim on a label without proving benefits in a human clincal trial.

“It’s frustrating,” Crum says. ““In fact, because there is no definition of the word probiotic from a legal perspective, it leaves our brands vulnerable to be attacked by parasitic lawyers who just want to extract value from large corporations because they can.”

“In my opinion, we need to honor the fact that all traditionally fermented foods are probiotic by nature instead of saying ‘Well you need the research to prove it,’” she says.

Mead’s Modern Moment

“Somewhere between wine, beer, and cider lives mead. An ancient libation like no other, mead has been a pleasant surprise to drinkers for eons. Norsemen would be thrilled to know that it has made a modern-day comeback.”

Mead was highlighted in an article in Tasting Table, “appreciated by everyone from Vikings to millennials.” Also known as honey wine, it is experiencing a modern resurgence. Mead makers are adding unique seasonings and spices to enliven their creations – but it needs to be at least 51% wine.

More meaderies are popping up – there is now at least one in every U.S. state. But liquor stores are still confused on where to put meads. The national sales manager of Chaucer’s Cellars – the country’s longest-running meadery – says most stores have no clue where to display mead.

Read more (Tasting Table)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Turning Brewery Waste Into Milk

Brewing giants Molson Coors and Anheuser-Busch are introducing new brands into the growing alternative milk category.. The brewers’ non-alcoholic, plant-based barley milks are “pioneers of a nascent sub-category in the fast-growing alternative milk field, with each product utilizing byproducts of their main business,” according to Ad Age.

Barley milk, notes the article, is a smart product that helps the brewers diversify their product portfolios. buoys declining beer sales, capitalizes on the growing wellness trend and upcycles a brewing byproduct.

Both brands (Molson Coors calls their barley milk Golden Wing; Anheuser-Busch, Take Two) are in the trial stage and aiming to raise awareness. Golden Wing is currently sold only in Southern California, and Take Two is only in the Pacific Northwest.

Take Two is positioned as an eco-friendly beverage, and is working with advocacy groups like the Upcycled Food Association. Anheuser-Busch produces about 8 billion pounds of spent barley a year.

“All that’s been removed is the sugar and starch. All this wonderful protein and fiber is still there,” says Holly Feather, head of marketing for Anheuser-Busch. She notes much of that spent grain is sent to commercial farms. “Saving the planet doesn’t have to be so serious. You can have a good time and do something good in the mix.”

Golden Milk, on the other hand, is aiming to be the “badass” alt milk alternative, and is marketing to health-conscious men.

“We want to invoke curiosity in consumers when they see our packaging and our bold voice, and ultimately get them to try our great-tasting products,” says Brian Schmidt, marketing manager for Molson Coors. “Longer-term, we want Golden Wing to unlock barley milk as the next big thing in the plant-based milk category, and we believe it can do just that.”

Read more (Ad Age)

- Published in Business

The “Periodic Table” of Fermented Foods

A pioneering “periodic table” of fermented foods was released this month, the first attempt to represent the breadth and range of fermented foods and beverages in graphic form.

This creation is the brainchild of Michael Gänzle, PhD, professor and Canada Research Chair in Food Microbiology and Probiotics at the University of Alberta. Gänzle is regarded as an expert in fermented foods and lactic acid bacteria. His recent research includes identifying a new taxonomy for the lactobacillus genus, a topic Gänzle spoke about in a TFA webinar.

“Non-traditional fermented foods are a big trend both in industrial food production and in culinary arts,” Gänzle said in an interview with TFA. “The periodic table may be the most concise overview on what is possible if all of the diversity of our benign and beneficial microbial helpers is recruited.”

The impetus for the table dates to 2014, when Gänzle and a colleague used a periodic table of beer styles in their food fermentation class. They wondered if it would be feasible to create a similar version for fermented foods.

Gänzle’s final version, along with his well-documented analysis of the table, was published in the journal Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. The table includes 118 entries of fermented foods, each coded for product category, country of origin, fermentation organism (like LAB, acetic acid bacteria or yeasts), fermentation substrate, metabolites and fermentation time.

Gänzle suggests the table is “quite useful for a number of things that may impact the development of fermented foods.” He says fermentation has “reemerged as a method to provide high-quality food.” A chef or producer can use the table to compare “differences and similarities in the assembly of microbial communities in different fermentations, differences in the global preferences for food fermentation, the link between microbial diversity, fermentation time and product properties, and opportunities of using traditional food fermentations as templates for development of new products.”

Because of its straightforward graphical layout, the table can quickly answer questions. A scan of it shows “which foods contain live fermentation microbes, which regions of the world have which preferences for substrates and fermented foods, which fermented foods are back-slopped and are fermented with host-adapted fermentation organisms.”

He stresses, though, that the table has its limitations, as it doesn’t cover every fermented food.

“The more I read the more likely I am to quote Plato’s rendition of Socrates’ statement that ‘I neither know nor think I know,’” Gänzle says. “Fermented foods are about as diverse as humankind.”

Gänzle plans to continue to revise the table on his personal website. Currently, he and two doctoral students are researching fermented soy and legumes, so look for the next updates to be in those categories.

- Published in Science

The State of Fermentation Education

The Covid-19 lockdown spurred aspiring home chefs around the world to try fermenting for the first time. DIY classes moved virtual and countertops filled with bubbling crocks of kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha and sourdough. Fermentation was one of the top pandemic hobbies.

For professional fermentation educators, this trend brought new, eager faces to classes. But now, as lockdown restrictions have eased, are people still wanting to experiment making their own microbe-rich food?

We asked three experts to share their thoughts on the current state of fermentation education — author and educator Kirsten Shockey (of The Fermentation School and Ferment Works), writer and educator Soirée-Leone (who can be found via her website) and chef, food scientist and fermentation educator Jori Jayne Emde (of Lady Jayne’s Alchemy and The Fermentation School). [Shockey and Soirée-Leone are both members of TFA’s Advisory Board.]

The question: What is the current state of fermentation education?

Kirsten Shockey, author and educator

Fermentation education is exploding. The time has never been better. The interest in fermentation — both as a topic and in hands-on engagement — keeps gaining momentum. People are both more curious and more confused than I have seen in the past. I think part of that is because with the boom of interest a lot of people are coming forward as experts sharing content without the prerequisites to inform accurately. For example, we see misinformation about the subtle differences in fermentation vs. culturing vs. pickling that end up leaving people who are just dipping their toes in the process a little less unsure. When these folx do engage with true experts they are enthusiastic students who enjoy soaking up all that they can and we see their anxieties dissipate. I speak from the experience of working with solid experts and their students through The Fermentation School. It has been beyond gratifying to work with an amazing group of really talented fermentation educators to grow quality online education and a dedicated “help” community through The Fermentation School. In my other educator hat, as an author, it is less clear to me how that media is working for education, but that is a bigger issue in that the publishing world itself is in a lot of flux.

Soirée-Leone, writer and educator

Folks are connecting with familial, cultural, and traditional roots through fermentation. They are building online communities to share knowledge, taking workshops, participating in residencies, checking books out from libraries, and attending fermentation festivals that are popping up all over the world.

While there is an abundance of information available through books and websites, some folks seek to connect in person through workshops. I find that it’s especially dynamic to teach and learn in collaborative environments to share skills and experiences. There are so many traditions, techniques, and riffs. It is exciting to learn about folks’ travels, study, and experiments — we each have a different fermentation journey and something to teach and learn.

Today is a far cry from when I first started cheesemaking in 1991 with one slim book that sang the praises of junket rennet. Now there are books sharing natural cheesemaking techniques, bloggers happy to answer questions, travelers bringing information home and sharing online, and workshops to attend.

Fermentation is accessible with rudimentary kitchen equipment and improvised incubators and cheese caves. Fermentation is empowering and engaging of all our senses—and learning new things about fermentation is a never-ending journey.

Jori Jayne Emde, chef, food scientist, fermentation educator

My perspective on this is it’s booming! There was a huge burst of interest for online learning during the pandemic, and I have not seen that slow down much. Fermentation is a trendy topic and word with, unfortunately, a tremendous amount of misinformation floating around out there. It’s an important time as an educator to really remain engaged with students, as well as capturing fermentation aspirants, guiding them towards proper and well informed education taught by experts in the field of fermentation and health.

- Published in Food & Flavor

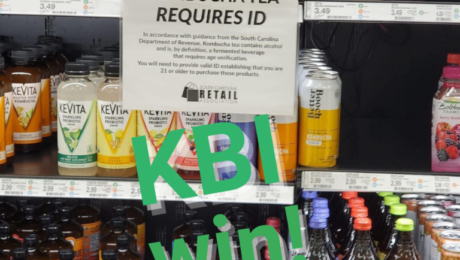

Kombucha Regulations Corrected in South Carolina

A win for kombucha brewers — after a confusing month for those trying to sell their products in South Carolina, they can now sell kombucha as a non-alcoholic beverage in the state.

South Carolina’s Department of Revenue (DOR) had categorized all kombuchas as alcoholic beverages. The state.’s regulations set a maximum alcohol content for beverages but no minimum, so any fermented beverage with any alcohol content would be considered alcoholic. Since kombucha fermentation produces a trace amount of alcohol, a brewer

would need to apply for a state alcohol license, and kombucha could not be sold to anyone under the age of 21.

S.C.’s law contradicts the U.S. legal definition of an alcoholic beverage, which is any product with 0.5% or more alcohol by volume (ABV).

After kombucha industry leaders contacted the state’s DOR and the South Carolina Retail Association (SCRA) to share advice and resources, the regulation was amended to exempt kombucha. Kombucha Brewers International’s leadership and legal counsel, along with producers Buchi Kombucha, GT’s Synergy Kombucha, Health Ade, Humm and Brew Dr., were involved.

“Every time we are called to support commercial producers to advocate on their behalf with government agencies, we validate the category,” said Zane Adams, chair of KBI’s board and co-CEO of Buchi Kombucha and FedUp Foods. “Our very existence means that kombucha is not a fad rather it is a necessary beverage segment that will only continue to grow. We appreciate every opportunity to interface with regulators to help them better understand our product and processes.”

“Crisis creates community,” adds Hannah Crum, KBI president. “Our mission is to advocate and protect kombucha and that’s exactly what we were able to do here thanks to the cooperation of several KBI member and non-member brands. We also appreciate that we were able to create new relationships with the SCRA and the S.C. DOR as we worked together to create a harmonious resolution.”

Most retail stores sell kombucha in the refrigerated juice section. In a press release, KBI shared three points for food regulators who may be unsure in what beverage category kombucha fits:

- Kombucha is not beer. Tax codes that lump kombucha with malt beverages are incorrect.

- Kombucha is an acetic acid ferment. Its fermentation process is similar to that for vinegar. Trace amounts of ethanol will be left in the final ferment, and they act as a natural preservative.

- Hard kombucha is an exception to non-alcoholic kombucha. Hard kombucha is intentionally made with a higher alcohol content, with the purpose to be sold and consumed as an alcoholic beverage.

KBI is currently lobbying for legislation that would exempt kombucha from excise taxes intended for alcoholic beverages. The KOMBUCHA Act, currently in Congress, proposes to raise the ABV threshold for kombucha taxation from its current level of 0.5% to 1.25%. KBI is encouraging the public to sign a petition in support of the act.

While KBI notes it would be ideal to create a new beverage category, “the process is long and arduous and requires a lot of financing for education and lobbying.”

- Published in Business

Zilber: Fermentation’s Endless Potential

David Zilber says the potential for fermented food is endless. “There isn’t any sort of food that doesn’t benefit from some aspect of fermentation,” he said. “There’s really no limitation to its application.”

Zilber, the former head of the Noma fermentation lab, co-authored “The Noma Guide to Fermentation” with Noma founder Rene Redzepi. In the fall of 2020, Zilber surprised the food world when he left his job at Noma to join Chr. Hansen, a global supplier of bioscience ingredients.

He shared his insight on fermentation on The Food Institute Podcast. An Oxford study found over 30% of the world’s food has been touched by microbes. Zilber, a microbe champion, says one of the best parts of fermenting with plant-based ingredients is the microbes don’t need to change.

“We do need to find ways to adapt them to new sources, but there will always be a place within the pie chart of what humans are eating on earth for fermentation,” he says.

Part of Zilber’s work at Chr. Hansen is in the plant-based protein alternative segment, fermenting plant ingredients to “bring this other set of characteristics” to a new food item. He advises fermenters using plant-based ingredients to make their ingredient list concise and pronounceable to consumers.

“I am a huge proponent for formulating recipes from whole ingredients,” Zilber says. “Keeping the ingredient list short and concise and using natural processes to achieve flavor or textual properties … because it is the healthiest way to eat.”

Across the spectrum of fermentation, he feels fermented beverages is the category where he sees the greatest opportunity.

Read more (The Food Institute)

- Published in Food & Flavor

A Nutrition Pro’s Fermentation Guide

Nutrition professionals need to share the details when recommending fermented products to clients. What are the health benefits of the specific food or beverage ? Does the product contain probiotics? Live microbes?

“There are a vast array of fermented foods. This is important because it means there can be tasty, culturally appropriate options for everyone,” says Hannah Holscher, PhD and registered dietitian (RD). But, she adds, remember that these are complex products.

Holscher spoke at a webinar produced by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) and Today’s Dietitian. Joined by Jennifer Burton, RD and licensed dietitian/nutritionist (LDN), the two addressed the topic Fermented Foods and Health — Does Today’s Science Support Yesterday’s Tradition? Hosted by Mary Ellen Sanders, executive director of ISAPP, the presentation touched on the foundational elements of fermented foods, their differences from probiotics, the role of microbes in fermentation, current scientific evidence supporting health claims and how to help clients incorporate fermented foods in their diets.

Sanders called fermented foods “one of today’s hottest food categories.” Today’s Dietitian surveys show they are a top interest to dietitians, as the general public often turns to them with questions about fermented foods and digestive health.

Here are three factors highlighted in the webinar that dietitians should consider before recommending fermented foods and beverages.

Does It Contain Live Microbes?

Fermentation is a metabolic process – microorganisms convert food components into other substances.

In the past decade, scientists have applied genomic sequencing to the microbial communities in fermented foods. They’ve found there’s not just one microbe involved in fermentation, Holscher explained, there may be many. The most common microbes in fermented foods are streptococcus, lactobacillaceae, lactococcus and saccharomyces.

But deciphering which fermented food or beverages contains live microbes can be difficult.

Live microorganisms are present in foods like yogurt, miso, fermented vegetables and many kombuchas. But they are absent in foods that were fermented then heat-treated through baking and pasteurization (like bread, soy sauce, most vinegars and some kombucha). They’re also absent in fermented products that are filtered (most wine and beers) or roasted (coffee and cacao). And there are foods that are mistakenly considered fermented but are not, like chemically-leavened bread, vegetables pickled in vinegar and non-fermented cured meats and fish.

“The main take-home message is that it’s not always easy to tell if a food is a fermented food or not. So you may need to do more digging, either by reading the label more carefully or potentially contacting the food manufacturer,” Holscher said. “When we just think of if live microbes are present or not, a good rule of thumb is if that food is on the shelf at your grocery store, it’s very likely that it does not contain live microbes.”

Does It Contain Probiotics?

The dietitians stressed: probiotics are not the same as fermented foods.

“Probiotics are researched as to the strains and the dosages to be able to connect consumption of a probiotic to a health outcome,” Holscher said. “These strains are taxonomically defined, they’ve been sequenced, we know what these microorganisms can do. They also have to be provided in doses of adequate amounts of the live microbes so foods and supplements are sources of probiotics.”

Though fermented foods can be a source of probiotics, Holscher notes: “In most fermented foods, we don’t know the strain level designation.”

“For most of the microbes in fermented foods, we’ve just really been doing the genomic sequencing of those over the last 10 years and so we may only know them to the genus level right,” she said. For example, we know lactic acid bacteria are present in kimchi and sauerkraut.

Holscher suggests, if a client has a specific health need, a probiotic strain should be recommended based on its evidence-based benefits. For example, the probiotic strain saccharomyces boulardii is known to help prevent travel-related diarrhea, and so would be good for a patient to take before a trip.

“If you’re looking to support health and just in general, fermented foods are a great way to go,” Holscher says.

The speakers recommended looking for probiotic foods in the Functional Food Section of the U.S. Probiotic Guide.

Does Research Support Health Claims?

Fermentation contributes to the functional and nutritional characteristics of foods and beverages. Fermented foods can: inhibit pathogens and food spoilage microbes, improve digestibility, increase vitamins and bioactives in food, remove or reduce toxic substances or anti-nutrients in food and have health benefits.

But research into fermented foods has been minimal, mostly limited to fermented dairy. Dietitians should be careful making strong recommendations based on health claims unless those claims are supported by research. And food labels should always be scrutinized.

“There’s a lot of voices out there that are trying to answer this question [Are fermented foods good for us?],” says Burton. “Many food manufacturers have published health claims on their labels talking about these benefits and, while those claims are regulated, they’re not always enforced. Just because it has a food health claim on it, that claim may not be evidence-based. There’s a lot of anecdotal accounts of benefits coming from eating fermented foods and the research is suggesting some exciting potential mechanisms. But overall we know as dietitians we have an ethical responsibility to practice on the basis of sound evidence and to not make strong recommendations if those are not yet supported by research.”

Reputable health claims are documented in randomized control trials. But only “possible benefits” can be linked to nonrandomized controlled trials. And non-controlled trials are the least conclusive studies of all.

For example, Burton puts miso in the “possible benefits” category because, with its high sodium content, there’s not enough research indicating it’s safe for patients with heart disease. Similarly, she does not recommend kombucha because of its extremely limited clinical research and evidence.

“We have to use caution in making these recommendations,” Burton says.

This is why Burton advises dietitians to be as specific as possible. Don’t just tell patients “eat fermented foods” — list the type of fermented food and its brand name. She also says to give patients the “why” — what is the benefit of this fermented food? Does it increase fiber or boost bioavailability of nutrients?

“Are fermented foods good for us? It’s safe to say yes,” Burton says. “There’s a lot that we don’t know, but the body of evidence suggests that fermentation can improve the beneficial properties of a food.”

Growing the Hard Kombucha Category

Hard kombucha is one of the fastest growing alcohol categories. Could it become the next cider, craft beer or even hard seltzer?

“That’s the big question, isn’t it. It’s up to us to do it,” says Joshua Rood, CEO and managing director of Dr Hops hard kombucha. “If we could make it so good that beer people get excited about it and wine people get excited about it, well now there’s potential for something really, really big. That’s how craft beer did it — they focused so much on quality that they just blew regular beer out of the water on quality and everyone went for it because it was just so much better. We’re committed to what’s possible.”

Declared the “drink of summer” in both 2020 and 2021, hard kombucha continues to grow this year. While still only a small segment (~$58 million) of the overall alcoholic beverage market, hard kombucha’s dollar sales growth is big at 60%. And this performance is at a time when sales are declining for both cider and hard seltzer.

“Seltzer is really homogenous, there’s no differentiation for the most part, whereas kombucha, every brand is very different,” says Joe Carmichael, co-founder of Local Roots Kombucha. “A lot more than craft beer, there’s a lot you can do with it.”

The two spoke on a hard kombucha panel at KombuchaKon, joined byJames Conery, manager of innovation at Sierra Nevada Brewing Co., and Steve Dickman, owner and brewmaster of Rocky Mountain Cultures and High Country Kombucha. The brewers agreed: hard kombucha can become as great as the craft beer category.

“For us, fermentation is part of the process,” Rood says.”There are live lactobacillus cultures still alive up to 11% ABV [Dr Hops ABV]. We chose that [alcohol level] because, for us, it was an expression of craft. It was a great style.”

The acidity of kombucha masks the taste of alcohol, making hard kombucha a smoother, tangier drink. While beer is made from grain, hard kombucha is made from tea leaves. This gives it its “better-for-you” profile, drawing on the antioxidants, vitamins and minerals in tea.

Kombucha brewers hoping to add a hard kombucha line need to realize that it is a “totally different business than non-alcoholic,” Rood says. The regulations are strict.

“If you’ve never done an alcohol booch and you’re going to get into it, some of the things we’re going to touch on, like probiotics or health claims, the TTB (Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau) has very big issues with health claims,” says Steve. “You cannot make health claims with alcohol. …There are a lot of regulations that come with it, a lot of ingredients you can’t use.”

Adds Conery, who runs the Strainge Beast brand for Sierra Nevada: “If you’re thinking about doing hard kombucha, you really need to research all the regulations before you start to do anything, before you even make it, so you know what you need to do.”

Even brewing hard kombucha is not without its challenges, too. Similar to beer, it requires the monitoring of key parameters — acidity, temperature, yeast strain, nutrients, time. But yeast is a delicate organism that can be difficult to manage, but which can alter the flavors of a brew.

Creating their first non-beer line came with growing pains for Sierra Nevada, one of the largest brewers in the U.S. Strainge Beast’s launch in 2020 required the company to make a substantial investment in its Chico, Calif., brewery, to seal off and isolate its beer operations from the hard kombucha line.

“As a brewer, I’ve spent my entire life making sure what kombucha is does not get into my brewery, because everything in kombucha is what you’d consider a beer spoilage organism,” Conery said. “We have to be very good about keeping what we’re doing with our kombucha segregated. As you scale up — especially with alcohol — there are a lot of things that can go wrong.”

Working with yeast is always a growing experience, “I’m still in the trial and error process,” Conery said. It took Sierra Nevada “quite a long time to find the correct yeast strain when we were fermenting to make our alcohol.” Yeast can create unique flavors — or funky, bad-tasting brews. A brewery will spend months exploring what yeast they want to use.

“It is the most interesting and horrible part of the production side, which is how to get the flavors you want, effectively,” Rood said. “When you’re dealing with a very acidic environment, that’s one of the biggest challenges and you want that acidity, which is part of the challenge. But you want your yeast to do a good, clean, healthy job of fermenting the alcohol.”

While both Sierra Nevada and Dr Hops approached hard kombucha with backgrounds in craft beer, Dickman at High Country Kombucha came from the kombucha world.When making hard kombucha, he brews the kombucha flavor he wants, then creates a neutral seltzer-like base. He blends the two together for the ABV value he desires, and says he likes this method as a way to experiment with acidity profiles.

“Kombucha was always a cool beverage, but now it’s bringing the party,” Dickman said.

- Published in Food & Flavor

Latest TikTokCraze: Gut Health

Doctors and microbiologists warn: despite what the latest social media trends proclaim, there’s no quick fix for better gut health. More influencers are promoting their “cures” — from drinking aloe vera juice to boiling apples — on TikTok. Their videos are getting millions of views — and are raising concerns from medical and scientific authorities.

“If somebody is claiming to have something that will immediately turn gut health around, you should be skeptical of that,” says Justin Sonnenburg, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford. The article in The New York Times notes Sonnenburg advocates for “long-term lifestyle habits that can benefit the gut — ones that rarely go viral or make their way to social media acclaim.”

Sonnenburg’s groundbreaking study last August showed fermented foods — like yogurt, kimchi, kefir, sauerkraut and kombucha — can increase the diversity of gut bacteria. “His research found that people who ate six servings of fermented foods each day saw these benefits — the equivalent of consuming one cup of yogurt, one 16-ounce bottle of kombucha and one cup of kimchi in a day,” the article continues.

The Times interviewed a panel of experts that included a dietitian, sociologist, gastroenterologist and Sonnenburg. They say, to improve your gut, change your lifestyle. They encourage eating more fiber, eating fermented foods, limiting processed foods and lowering stress levels.

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Health