“Consumers Have Changed” — State of Natural & Organic Industry

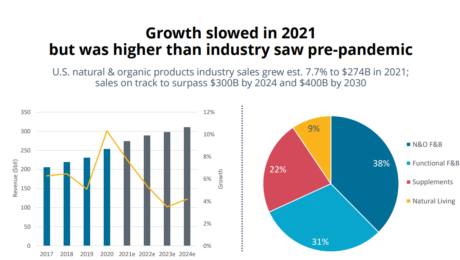

After the pandemic pantry stock-up of 2020, when grocery food purchases skyrocketed, sales of U.S. natural and organic products have slowed. Sales increased 7.7% to $274 billion in 2021. That’s a lower growth rate than the 13% pace seen at the height of the pandemic in 2020, but still higher than the pre-pandemic level of 5.3%. Sales are forecast to exceed $400 billion by 2030.

“For an industry that was always called a fad and a niche, to be able to hit $400 billion by 2030 just indicates that we have moved mainstream, ”said Carlotta Mast, senior vice president of the New Hope Network (a division of Informa PLC), which produces Natural Products Expo West. The stats were presented during the expo’s State of Natural & Organic Industry presentation.

Speaking to a standing-room only crowd, industry experts shared how the Covid-influenced sales boost will stay because “consumers have changed.”

“They’re paying more attention to their health and wellness, they’re investigating new brands, they’re cooking more at home and this is creating longer-term opportunities for this industry,” Mast said.

After a two-year hiatus, 2022 marked the return of Expo West, the largest natural products show.The event was smaller than in pre-pandemic times. There were 57,000 attendee registrations this year, versus 86,000 in 2019; 2,700 exhibitors, compared with 3,600.

Kathryn Peters, executive vice president at SPINS (a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products), said wellness-positioned brands are the main source of CPG growth and innovation. She cited that, while wellness products represent only 25% of the market, they produce 68% of growth.

“The pursuit of wellness is driving this industry and its changing consumers,” Peters said. “People are paying attention to what they’re putting in and on our bodies.”

Functional Flourishing

The natural, organic and functional food and beverage category — where fermented products reside — drives nearly 70% of natural product sales. Functional food and beverage sales grew 8.3% to $83.78 billion in 2021. Functional beverages, frozen foods and snacks are the top selling items in the functional space.

From kombucha to kraut, from chocolate to yogurt, dozens of fermented brands exhibited at this year’s event.

Esther Lee, CEO of Korean fermented tea brand IDO tea (a long-time participant in Expo West), doesn’t think it’s wellness attributes that initially attract consumers to functional beverages. She says it’s packaging and ingredients.

“Later on they usually realize their body feels different after using our products for weeks,” Lee said.. IDO Tea is currently sold in Korea, online on Amazon and in small shops in Los Angeles. It was at Expo West looking for a U.S. distributor.

New brand Miso Good attended the show as a relaunch. Founder Rhonda Cole began the woman-owned, start-up company with her daughter Lauren in 2019. The Florida-based brand then took a hiatus during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It has been difficult the past few years,” Cole said, adding she hopes to find success at the show. “Our motto is ‘ancient superfoods for the everyday eater’ and our fermented miso is great as a soup, sauce or condiment.”

It was the first Expo West for Local Culture Live Ferments, a Northern California brand that sells small batch sauerkraut, kimchi, hot sauce and brine tonic.

“We’re too small to be big, but too big to be small. We’re in this in-between stage and that’s very much why we’re here, to break through that threshold and get our product out to people,” said Chris Frost-McKee, director of operations. Local Culture was one of 40 brands selected by food distributor KeHe at their TrendFinder Event (read more about Local Culture in TFA’s Q&A). “We were maxing out our range with our current distribution. Our goal here was to open doors and make connections, and we’ve accomplished that.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Mexico’s Fermented Drinks

“Most people outside Mexico are familiar with the country’s tradition of distillates and beers. Far fewer have experienced an entire galaxy of beverages, like tejuino , that are much less available here in Southern California. They are made with Indigenous-based practices, typically inside people’s homes, usually with a plant, like corn, that’s already used for a bunch of other things in Mexico.”

A Los Angeles Times article highlights Mexican fermented drinks, like tepache, tejuino and pulque. They’re common in Mexico, brewed in home kitchens and sold at roadside stands. But in L.A. County where almost 4 million people trace their roots to Mexico, these rustic fermented beverages remain uncommercialized. Are Mexico’s artisanal, fermented drinks the last “importation of Mexican culinary practices to the United States?” the article speculates.

Tepache is the closest to breakthrough status in the U.S., with more companies offering canned versions. De La Calle Tepache was started by co-founder Rafael Martin using his grandmother’s recipe (he later studied fermentation in college). Ingredients in De La Calle Tepache are traditional to and sourced from Mexico. Martin describes his clientele as “chipsters” crowd – a slang term for Chicano hipsters.

Pulque, on the other hand, is difficult to replicate. The fermented aquamiel sap (from the core of the agave plant) only lasts two days before it starts to go bad. Some academics argue ferments from Mexico should be “more aggressively cataloged, preserved and consumed.” Scientists from the University of Arizona and four universities in Mexico recently published their research highlighting 16 of Mexico’s fermented beverages.

Read more (Los Angeles Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Experimenting with Yeast

The craft brewery industry is seeing increased innovation — and beer drinkers eagerly embrace these novel experiments. Brewers are turning to new, unique yeast profiles for distinctive drink styles.

“Whether a brewer chooses to ferment hot and quick or slow and cold is in large part a direct response to what microorganisms – i.e., yeasts – they select to turn their sugar water (aka wort, in beer-speak) into beer; and depending on the temperature and amount of yeast used, the same yeast profile can yield different flavors. Will a yeast profile influence the drinker’s experience?” reads an article in Sauce magazine. “The past several years have seen substantial innovation in the fermentation process leading to greater efficiency and efficacy.”

Yeast isolates used more and more by craft brewers include the lager-style Lutra kveik (kveik being the word for yeast in Norwegian). Kveik strains produce fruity, tropical-tasting beers. Another yeast rising in popularity among brewers is Sourvisiae, which produces a more sour flavor.

Read more (Sauce)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Study: What Bacteria Survive Digestion?

New research has explored how lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in sauerkraut and tibicos survive digestion and change gut microbiota composition.

This work, published in Frontiers in Microbiology, investigated how a fermentation production process affects LAB and yeast microbial viability and probiotic potential. Though there are studies that demonstrate health benefits of fermented foods, few “explore how being part of a whole fermented food matrix affects microbial viability during fermentation, storage and gastrointestinal (GI) transit.”

The study focused on non-dairy, botanical fermented foods, defined as “microbially transformed plant products rich in health-promoting components.” Tibicos and sauerkraut were chosen because recent research had found the microbial diversity of the two ferments “far exceeded that of dairy-based ferments, as well as containing the largest numbers of potential health-promoting gene clusters.” The tibicos studied was sugar-based while the sauerkraut was brine-based, and both contained various strains of LAB and bioactive components.

Ginger, cayenne pepper and turmeric added to tibicos were all found to have different survival rates in the digestion tract. These functional spices are often added to fermented products for their anti-inflammatory and sensory properties, but their microbial proliferation had never been adequately explored. Cayenne was the clear winner, as adding it to tibicos “significantly improved the survival rate of LAB during simulated gastric and small intestinal digestion compared to ginger and turmeric.” Ginger in tibicos had a higher rate of LAB survival than turmeric, though neither had a significantly higher LAB survival rate than plain tibicos. But adding ginger significantly increased and sustained microbial viability of LAB.

The research team — from University of Melbourne — did not perform the study on human subjects, but simulated upper gastrointestinal digestion and colonic fermentation tests using pig feces.

Some other significant findings:

- For an optimal microbial survival rate of 70-80%, tibicos should be consumed within 28 days, and sauerkraut within 7 weeks.

- Sauerkraut made with different salt concentrations did not show any significant variation in LAB counts.

- Inoculating sauerkraut with a starter culture increased LAB counts during fermentation and storage. But, by the end of storage, the LAB counts in the inoculated sauerkraut “dropped to undetectable levels.”

- Spontaneously-fermented sauerkraut LAB counts remained stable through the storage period.

“Botanical fermented foods are cheap, easily made, and consumed globally,” the study concluded. “This makes them excellent candidates for the dietary management of pro-inflammatory noncommunicable diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

Fermentation Takes Center Stage in the Coffee Industry

Coffee production is an enormous, global industry, but the fermentation of coffee beans has not been a major focus for producers — until now. Highlighting the scope of the industry and this new emphasis on the impact of fermentation, The Fermentation Association’s webinar El Estado Del Arte En La Fermentación Del Café generated registrations from around the world. Registrations were nearly twice what TFA’s largest webinar generated.

TFA’s first Spanish-language webinar, the final count of registrants was well over 1,000, and came from 42 countries. The continents of North and South America, Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia were all represented. Registrations from key coffee-growing areas — Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Honduras — accounted for 70% of those that signed up. But we had folks from Ethiopia, Belgium, Nepal, Laos and the United Arab Emirates as well!

TFA partnered with the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) last year and produced a webinar in August entitled The State of the Art in Coffee Fermentation. SCA’s Technical Officer, Dr. Mario Fernandez, brought together two esteemed speakers in the industry that discussed different approaches to fermentation. Felipe Ospina, CEO of Colors of Nature Group, and Ruben Sorto, CEO of BioFortune Group, represented two sides of the subject. At the risk of oversimplifying, Ospina favors traditional, natural fermentation methods. Sorto is investing in how to apply the technologies and processes from other food and beverage production industries — like winemaking, for example — to enhance the end product. Ospina connected from offices in Japan; Sorto spoke from his Honduras operations.

These speakers also were part of last year’s English-language webinar on the same subject and with the same speakers. The response to that session was so overwhelmingly positive that it led us to reprise the session, but to do it this time in Spanish. It was a bit challenging for our non-Spanish-speaking TFA team, but we were helped out enormously by our colleague from Monterrey, Mexico, Raquel Guajardo, a fermentation author, educator and entrepreneur. Dr. Fernandez, after being instrumental in planning and promoting both sessions, was called away suddenly on the day of this webinar. Ms Guajardo filled in admirably as our last-minute replacement moderator.

We look forward to more collaborations with SCA. Watch for another joint effort in late April/early May, after SCA’s Specialty Coffee Expo in Boston, April 8-10.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

“Bacterial Bully” Could Create Healthier & Tastier Fermented Foods

Microbiologists have long considered that there are two distinct categories of energy conservation in microorganisms: fermentation and respiration. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) use fermentation, making it central to food and drink production and preservation since the dawn of man.

But researchers at the University of California, Davis, and Rice University discovered a LAB species that uses a hybrid metabolism, combining both fermentation and respiration.

“These are two very different things, to the extent that we classify bacteria as basically one or the other,” said Caroline Ajo-Franklin, a bioscientist at Rice University and co-author of the study. “There are examples of bacteria that can do both, but that’s like saying I can ride a bicycle or I can drive a car. You never do both at the same time.”

“What we discovered is a LAB that blends the two, like an organism that’s not warm- or cold-blooded but has features of both,” she said. “That’s the big surprise, because we didn’t know it was possible for an organism to blend these two distinct metabolisms.”

The species — lactiplantibacillus plantarum — is what scientists call a bacterial bully because it takes advantage of two distinct metabolic processes, according to a press release from Rice on the study. These systems were “not previously known to coexist to acquire the fuel they burn for energy.”

“Using this blended metabolism, lactic acid bacteria like L. plantarum grow better and do a faster job acidifying its environment,” said Maria Marco, a professor in the food science and technology department at UC Davis and the study’s co-author [and a TFA Science Advisor].

The discovery is significant for food and chemical production. New technologies that use LAB could now produce healthier and tastier ferments, minimize food waste and change the flavors and textures of fermented food.

“We may also find that this blended metabolism has benefits in other habitats, such as the digestive tract,” Marco said. “The ability to manipulate it could improve gut health.”

The study began with a puzzle: the realization that genes responsible for the electron transfer pathway in mainly respiratory organisms also appear in the LAB genome. “It was like finding the metabolic genes for a snake in a whale,” Ajo-Franklin said. “It didn’t make a lot of sense, and we thought, ‘We’ve got to figure this out.’”

While the Davis lab studied the genome, the team at Rice carried out fermentation experiments on kale.

“It wasn’t our first choice,” said Rice alumna and co-lead author Sara Tejedor-Sanz (now a senior scientific engineer in the Advanced Biofuels and Bioproducts Process Development Unit at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab).

“We performed some initial experiments with cabbage, since that’s a known fermented food — sauerkraut and kimchi — in which lactic acid bacteria are present,” she said. “But there were technical difficulties and it didn’t turn out so well. So we looked for another food to ferment where LAB could be found in its ecological niches.

“Kale has compounds like vitamins and quinones that lactic acid bacteria use as cofactors in their metabolism, and are also involved in interacting with the electrodes,” she said. “We also found fermenting kale to make juice was a trend. It sounded perfect for our biochemical reactors.”

The study showed LAB enhances metabolism through a FLavin-based Extracellular Electron Transfer (FLEET) pathway that expresses two genes (ndh-2 and pp1A) associated with iron reduction, a step in the process of stripping and incorporating electrons into ATP (adenosine triphosphate (ATP), energy-carrying molecule).

Because LAB’s genome has evolved to be small, thus requiring less energy to maintain, the wide conservation of FLEET must serve a purpose, Ajo-Franklin said.

“Our hypothesis is this helps bacteria get established in new environments,” she said. “It’s a way to kick-start their metabolisms and outcompete their neighbors by changing the environment to be more acidic. It’s being a bully.”

That the FLEET pathway can be triggered with electrodes offers many possibilities, she said. “We found we can use the hybrid metabolism in food fermentation,” Ajo-Franklin said. “Now we have a way to change how food may taste and avoid failed food fermentations by using electronics.”

“We may also find that this blended metabolism has benefits in other habitats, such as the digestive tract,” Marco said. “The ability to manipulate it could improve gut health.”

Ajo-Franklin noted LAB are commonly found in the microbiomes of many organisms, including humans. “You can already buy it in health food stores as a probiotic,” she said. “The human gut is an anaerobic environment, so LAB have to keep a redox balance. If it oxidizes carbon to gain energy, it has to figure out a way to reduce carbon somewhere else.

“Now we think if we provide another electron donor or acceptor, we could promote the growth of positive bacteria over negative bacteria.”

UC Davis graduate student Eric Stevens is co-lead author of the study. Co-authors are Rice graduate student Siliang Li; at UC Davis, graduate students Peter Finnegan and James Nelson, and Andre Knoesen, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, at UC Davis; and Samuel Light, the Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Microbiology at the University of Chicago.

Ajo-Franklin is a professor of biosciences and a CPRIT Scholar. Marco is a professor of food science and technology.

The National Science Foundation, Office of Naval Research, the Department of Energy Office of Basic Energy Sciences and a Rodgers University fellowship supported the research.

The study results were published in the journal eLife.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Changing Face of Specialty Coffee

Gesha (or Geisha) coffee has been the favored variety in coffee competitions for over 15 years. But recently specialty coffee brewers are using a new variety: the species C. eugenioides. An article in Perfect Daily Grind details the shift.

As Gesha became the preferred choice of coffee champions (seven of the World Brewers Cup (WBrC) champions from 2011 to 2019 used Gesha), the price started to rise. Gesha production, common in Panama, began to increase in other countries wanting to farm the popular variety, notably Colombia and Ethiopia. But increased production led to some lower-quality Geshas coming to market.

In recent years, producers have opted for lesser-known coffees, notably eugenioides, a species of arabica originating in East Africa. Its flavor profile is unique, with notes of tropical fruit, and has lower levels of caffeine. But it can be a risky variety. Eugenioides trees are small and produce small cherries, and they take years to grow.

A possibly more sustainable option for the industry: innovative processing techniques. The 2015 WBrC winner won using carbonic maceration process, a fermentation technique used in the wine industry.

“Fermentation is an effective way to influence the aroma and taste of coffee. It changes the acidity levels and body of coffee,” explains Chad Wang, founder of VWI by Chad Wang, a specialty coffee judge and the 2017 WBrC winner. “Fermentation can significantly help coffee farms to offer different tastes without having to change too much.”

[To learn more about fermentation in coffee, check out TFA’s webinar with the Specialty Coffee Association “The State of the Art in Coffee Fermentation.” The two organizations will be partnering again for a Spanish language version of the free webinar on March 3.]Read more (Perfect Daily Grind)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Analyzing the World’s Fermented Beverages

Can indigenous fermented beverages play a prominent role in a healthy diet? Biochemists studied four commercial products – kefir and ryazhenka from Russia, amasi and mahewu from South Africa. Their research was published in the journal Foods.

Researchers from the Institute of the Research Center of Biotechnology of the Russian Academy of Science (RAS) and South Africa’s Durban University of Technology discovered key elements of the fermented drinks. The three that are milk-based had more antioxidants than the corn-based one, while the corn drink (mahewu) was “better at suppressing the angiotensin-converting enzyme.” Kefir and ryazhenka, meanwhile, have a more diverse composition of fatty acids.

“Usually, food is considered only as a source for sustenance. However, more and more people (are starting) to believe that it also should preserve and improve health,” Konstantin Moiseenko, co-author of the study and a research fellow at RAS in Moscow. He notes modern science allows “mankind to look differently at the usefulness of traditional, centuries-old foods. Our research focuses on fermented products, which regular consumption can potentially prevent atherosclerosis, hypertension and thrombosis.”

Read more (Lab Manager and Foods)

“More Brew, Less Buzz”

The craft beer industry has been dominated by strong brews or alcohol-free varieties. The New York Times highlights how “craft brewers are increasingly aiming for the sweet spot in the middle.” Low-alcohol beers are growing in popularity, appealing to consumers who want moderation not abstinence.

“There’s just this completely unexplored space,” says Sean Boisson. He started Bella Snow Soft Ale in California, which focuses on ales with no more than 2.4 percent ABV (about half the strength of a traditional beer). Christophe Gagné, owner and brewmaster of Jack’s Abby Craft Lagers in Massachusetts, created a series of low-alcohol beers he calls the 2% Beer Initiative, which has become a bestseller. “I would much rather have two beers and not fall over,” he adds.

The trend is reflecting the preferences of older beer drinkers. Their bodies can’t handle the aftereffects of alcohol and they want to ease back into their IRL responsibilities without a hangover.

“We’re not surprised that lower-ABV. beers are coming of age because, well, millennials are coming of age,” said Lester Jones, the chief economist for the National Beer Wholesalers Association.

Brewers note low-alcohol beer is a challenge. A beer with less alcohol is not easier or even cheaper to produce. Low-ABV beers require less malt (the grains supplying the sugars that are fermented into alcohol) but, if hops are too plentiful, the flavor becomes bitter. And a quality low-alcohol beer also can’t be watery.

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Evidence of Fermented Health Benefits

We’re on the cusp of a new generation of health-promoting foods, foods that will harness the power of microbes present in fermented foods and beverages.

Paul Cotter, head of Food Bioscience Department at Teagasc Food Research Centre in Ireland, envisions a future system where fermented foods are made with strains having scientifically-proven health-promoting benefits. His lab is integrating microbiome and metabolic data and using DNA sequencing to drill down to specific health benefits.

“We’ve really only scratched the surface as to the real potential of all those different microbes and what they could be doing,” says Cotter, who is also the principal investigator with the APC Microbiome Ireland. “Whether a particular food is health promoting or not will be dictated by what microbe is in there and can only be proved by carrying out the appropriate studies.”

Cotter was a speaker at TFA’s conference FERMENTATION 2021. He made a case for establishing minimum standards for fermented foods and beverages. In his scenario, kombucha or kefir couldn’t be labeled as such without using a scientifically-backed combination of microbial strains.

“That ensures that the kind of pseudo fermented foods — the foods that are fermented but not really with the right microbes — don’t get on the market or can’t be distinguished,” Cotter says.

Not all Fermented Foods are Equal

There is scientific evidence of the health benefits of frequently and regularly consuming fermented foods and beverages. They can prevent illness, provide a source of live and active microbes, improve the digestibility of foods, increase certain vitamins and bioactive compounds and remove or reduce toxic compounds like lactose.

“Ultimately, I’m a scientist and so I want to see proof that underpins the claims associated with a particular food,” Cotter says. “While there’s a lot of good information out there, I think also some of the claims are doing a disservice to the fermented food industry and to those who make fermented foods in their homes because they’re overstating the potential health benefits.”

Problematic, too, are fermented foods made with shortcuts and additives. Cotter’s lab is currently studying kefir, and they found that not all are equal. Traditional kefir has been documented as helping to reduce weight and improve cholesterol and liver triglyceride levels. But some brands of commercial kefir they studied didn’t produce those same health benefits. And they found that some of the kefir on the market was nothing more than watered-down yogurt.

“Consumer beware: the benefits weren’t the same for each kefir and differ depending on what the microbes present in the kefir were,” says Cotter, a self-described fermented foods nerd. ”I think that’s a problem for lots of other fermented foods too, and I really feel for consumers who don’t have a microbiological background and are reading a label and assuming that they are consuming a fermented beverage or fermented food that has lots of beneficial microbes in there and is made in the artisanal way that that food has been made over hundreds of different years.”

What are the health benefits?

Cotter’s lab has used in-depth analyses to detail the microbial composition of a food, including naming the microorganisms present and their capabilities. They’ve identified “completely novel species that had never been found previously,” Cotter says. An example is African fermented food, which contains a huge diversity of microbes, including ones not typically found in fermented foods in the West.

The highest level of what’s called “Health Associated Gene Clusters” are in fermented foods, specifically those brine- (like sauerkraut and kimchi) or sugar-based (kefir and kombucha). Cotter notes the genes in fermented foods are health promoting because the microbes are closely related to probiotics.

“What we can do is to try to harness the microbes that are present and use them in a way that facilitates large-scale production,” Cotter says.