Noma Goes DTC

Noma is coming into the home kitchen.

The fermentation-focused restaurant, lauded as one of the top restaurants in the world, is selling its first line of packaged products. Two garums — vegan Smoked Mushroom and vegetarian Sweet Rice and Egg — will soon be available to ship internationally through the brand’s website, Noma Projects.

“It’s a space for us to channel our knowledge, our craft and experimentation into a new endeavor,” says René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant.

Redzepi shared details of the launch in a video on the site. Noma Projects will include pantry products and community-based initiatives, “a way for us to address issues we care about through the lens of food.”

Noma’s Pantry Staples

The garums are Noma’s “take on a 1,000-year-old recipe that we’ve been developing over the past two decades.” Redzepi says the “potent, umami-based sauces” have been the “key to our success at Noma in our vegetarian and vegan menus.

He hopes the garums will help more people cook plant-based meals, announcing in the video: “We want to help you bring more vegetables into your everyday cooking.” The garums provide the flavor of meat and fish without the animal. The website description notes: “Shifting towards a more plant-based diet is the easiest way for an individual to help the environment. We hope these garums will do the same for you that they’ve done for us, help inspire and create more delicious plant-based meals when you cook at home.”

These products were developed in Noma’s Fermentation Lab, where dozens of pantry staples were tested before landing on the garums. A garum is the “concentrated essence of its main ingredient” with a strong umami flavor, and Redzepi describes it to the WSJ. Magazine (the luxury magazine published by Wall Street Journal): “It has the potency of a soy sauce, except it tastes of what it is.” Both are brewed with koji rice, what Redzepi calls the “mother fungus.”

The garums are currently fermenting and will be ready for shipping in the fall or winter. The expected price point is $20-$35 for a bottle.

And more garums are in the works. Noma Fermentation Lab director, Jason Ignacio White, says a roasted chicken wing garum is next.

“It tastes like super chicken stock with umami,” White tells WSJ. Magazine, ”so it’s a familiar flavor, but there’s something about it that you can’t really put your finger on, that makes your tongue dance.”

Improving Profitability

Despite Noma’s expensive tabs — the 20-course tasting menu costs 2,800 Danish kroner (or around $447), and the wine pairing is another 1,800 Danish kroner (or around $287) — in the 18 years since it opened, the restaurant has hovered at only a 3% profit margin. Redzepi hopes Noma Projects will make more money. While it is “a family-run garage project,” its goal is to reach a million customers.

Like many restaurants around the world, Noma shut down during the pandemic. They reopened as a burger and wine bar in June 2020, and the walk-up, outdoor dining experience was such a success that it became a permanent restaurant, POPL.

Noma resumed regular operations on June 1, 2021. The pandemic closure allowed Redzepi and his team to finally tackle the retail brand, something he said they had debated for years.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Dunkin’ Kombucha

Move over, Dunkin’ Coffee. The chain known for its coffee and donuts is branding itself into new territory — kombucha. Dunkin’ is the first chain restaurant (to TFA’s knowledge) to make their own kombucha. They are testing their new Dunkin’ Kombucha — made in two flavors, Fuji Apple Berry and Blueberry Lemon — in select restaurants in the Albany, N.Y., and Charlotte, N.C., markets.

According to their release, “Dunkin’ continues to democratize delicious by testing kombucha for the first time.” In any case, this test is further evidence of the fermented tea’s increased popularity as an alternative to soda.

Read more (Dunkin’)

- Published in Business

“Magic Happens”

René Redzepi graced the pages of The New York Times again, but this time in the Arts section. The chef and owner at the world-famous restaurant Noma shared impressions on different musical pieces and other musings with writer Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim. One of his favorites: Mort Garson’s “Plantasia” (an electronic album meant for plants) that he plays in Noma’s greenhouse.

Redzepi also touched on fermentation. “It’s an antidote to the world where everything is so fast; on-demand; lightning speed. To actually have things that you have to wait for and then something magic happens, I love that. The happiest people I know are people who are in nature all the time: foragers, bakers, fermentation experts. Sometimes I envy that focus. My job is to be at the center of everything that is going on.”

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Pairing Sake with Food

Does sake go well with Western dishes? Josh Dorcak, chef of Japanese restaurant Mäs, tells Forbes why he thinks sake is an excellent pairing with all food types, maybe even more so than wine.

“Sake pairs with everything,” Dorcak says. “With wine often it seems like there are these rules that one must follow while sake often fits the bill for creative pairings.”

Read more (Forbes)

- Published in Food & Flavor

The Flavors of Fermentation

From pickling foraged plants to experimenting with koji to vacuum-sealing tempeh, more chefs are experimenting with fermentation. Insights “for menu developers seeking unique concepts and ingredients” were shared during a session at the Research Chefs Association’s RCA+ virtual conference.

Sandor Katz, noted author and educator, discussed how research kitchens can increase their fermentation activities, from creating interesting flavors to expanding food preservation.

“[Fermentation] can elevate the plainest of foods into flavor sensations,” Katz said. “Its uses in culinary traditions around the world are incredibly diverse, and yet visionary chefs are experimenting with exciting new applications of fermentation.”

Read more (Food Business News)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Zilber on Leaving Noma for Bioscience Corporation

A sustainable food industry will be built by flavor, says David Zilber, noted chef and food scientist.

Zilber made major headlines and surprised many in October when he left his job as head of the fermentation lab at Noma for a food scientist position at Chr. Hansen, a global supplier of bioscience ingredients. Noma, a two-Michelin star restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark, has been regularly ranked one of the best restaurants in the world. In 2018, Zilber co-authored a bestselling book on fermentation with Noma co-owner Rene Redzepi.

In an Instagram live interview last week with Al Jeezera’s Femi Oke, Zilber elaborated on why he traded an apron for a lab coat. The global food system, Zilber says, is unsustainable. Waste is prevalent, food is created with long footprints, agricultural production is shrinking, meat is heavily consumed and large corporations control the industry.

Transforming Vegetables

“What I’m trying to do in my work is to make vegetables as God damn tasty as they can possibly be by using microbes, using things that are already at our disposal, and convincing people that this might have to have a little bit of a longer inventory life while you let it ferment, while you build a stockpile, but this is the result, this is why you’ll be able to convince people why eating this way is healthy for them and the planet,” he says. “Flavor is king.”

Ingredients created by Denmark-based Chr. Hansen (the company has 40,000 microbial strains used as natural ingredients) feed 1-1.5 billion people a day. These include microbes in yogurt and yeast in beer.

“I work with them to try and make the food system more sustainable, to get more people eating vegetables,” Zilber says, adding that 30% of every calorie consumed by humans is fermented by bacteria, microbes or fungus. “No matter what we eat in the future, that’s still going to be the case. That slot of the human diet still needs some form of microbial transformation, whether it’s meat or dairy or oat milk or peas. I work to figure that out.”

It’s a different philosophy compared to the food technology many new companies are utilizing to create alternative proteins like Beyond Burger. He complimented the company for their high standards, but he says a Beyond Burger patty is not a replacement for a juicy, beef burger. People pay more for an inferior eating experience.

“At the end of that day, that will not cut it,” Zilber says. “Why does food have to be that processed to be purportedly that delicious? With some skilled tricks in the kitchen, with some ninja jiu jitsu behind the stove, you can make vegetables really, really delicious.”

Sustainable Food Systems

A sustainable food system will look much like one from 300 years ago, Zilber hypothesizes. It will be localized, where people purchase food produced close by. Modern practices of shipping ingredients and processed food around the globe are harmful to the environment.

“A truly sustainable food system looks far more decentralized than [the current one] does right now. There are [only a] very few stakeholders that are responsible for really a lot of calories,” he continues.

Oke questioned how Zilber could change a broken food system controlled by large companies when he now works at one of the major companies.

“If you want to be an idealist, that’s great, you might end up being a martyr,” Zilber says. “Sometimes you have to work within those contradictory institutions to try to do as much good as possible.”

Restaurant Industry’s Responsibility

The restaurant industry plays a part in it too, Zilber says. Workers are stretched thin, overworked, underpaid “and then extremely vulnerable in a time of crisis.” The pandemic has exposed and highlighted these problematic parts of the restaurant business.

Zilber says there are still too many restaurants. It’s hard to find good cooks, and staff is often undertrained.

“I took a step into food production myself. Maybe more of these cooks, more of these people who are passionate about food, need to consider options beyond just the restaurant setting and see value in becoming a farmer, becoming a distributor, becoming someone who decides how those calories are made because restaurants aren’t the full picture of the food system,” he continues. “There are a lot of talented people within it who know food, who understand it, who understand the human experience of what it means to make good tasting food and satisfying food. There’s other places for them to work as well.”

- Published in Business

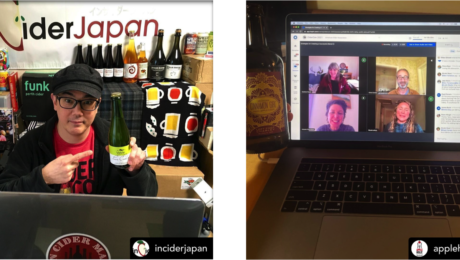

7 Takeaways for Cideries in 2021

Despite a year when cideries around the world were forced to close down taprooms and cancel restaurant sales due to the pandemic, cider sales grew 9% in 2020.

“I know some of you are barely hanging on — but you are hanging on,” said Michelle McGrath, executive director of the American Cider Association (ACA). “We did not waver, we held our shares and we kept growing.”

McGrath presented industry statistics at CiderCon 2021, the ACA’s annual global cider conference. Because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, the conference was virtual this year. Nearly 800 people from 18 countries and 41 states attended the three-day conference.

Smaller, local cider brands sparked consumer interest in 2020. Sales of regional cider brands grew 33%, while national brands declined 6%.

The impact of the pandemic, though, has been severe on certain sectors of the industry. On-premise cider sales (in restaurants, breweries and taprooms) declined nearly 70% from 2019.

“We’re resilient, we’re tough, we’re savvy. You couldn’t have predicted how your business would have stood up to a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic,” said Anna Nadasdy, director of customer success at Fintech, a data company for the alcohol industry.

Nadasdy’s keynote on expected consumer trends in 2021 cited the key drivers influencing consumer behavior — the economy, politics and natural disasters. Here are seven of her takeaways for cideries:

- Consumers Buying all Alcohol Types

Though consumers have long been loyal to one type of alcohol — beer, wine or spirits — the “beer guy or wine gal” label is disappearing. Over one-third of consumers are purchasing from all three major categories.

Hard seltzer is the third largest beer segment (16% of dollar share, behind domestic premium and imported beers), but it’s the fastest growing. This is exciting for cider makers, Nadasdy notes — hard seltzer in 2018 was the size of the cider market today.

- Fruit-Flavored Cider is Growing

Though apple cider still dominates the cider market with 52% of sales, fruit-flavored cider grew three points in the past year to 12% of sales. The top three fruit-flavored products are: Ace Pineapple Craft Cider, Incline Scout Hopped Marionberry Cider and 2 Towns Ciderhouse Pacific Pineapple Cider.

(Other products in the cider category include: mixed flavors, dry cider, seasonal cider/perry, herb/spice cider.)

- Cider is Making Waves in Craft Beer

Cider — tracked as part of the overall craft beer category — is proving a worthy participant.Cider has 11% of the dollar share, second only to the category leader, India Pale Ale (41% of the market).

“That’s really impressive for such a small base,” Nadasdy says. “Even though you guys are a smaller segment, you still have a lot to contribute to the overall beer category. And I think it’s important when you’re having these conversations with retailers that you are able to point out these wins.”

- Hard Kombucha is Gaining Ground

Cideries are competing with hard kombucha. Though hard kombucha is a fermented tea and not a cider, retailers consider hard kombucha and cider comparable drinks. And hard kombucha sales are growing quickly.

“Although small now, keep an eye on (hard) kombucha,” Nadasdy said.

- Prepare for Changed On-Premise Sales

Once wide-spread vaccination is in place and on-premise dining returns, expect fundamental changes such as more online ordering, healthier menu choices and a rise in food tech like tablet menus. The National Restaurant Association listed other significant changes that will impact cideries:

- Streamlined menus. There will be fewer menu items, with 63% of fine dining operators and half of casual and family dining operators saying they will reduce their offerings.

- Alcohol-to-go. Seven in 10 full-service restaurants added alcohol-to-go during the pandemic. Thirty-five percent of customers say they are more likely to choose a restaurant that offers alcoholic beverages to-go.

- Rosé-Flavored Cider is Out

Every brand of rosé-flavored cider is losing sales. The top three brands showing the most significant losses in this category are: Angry Orchard, Bold Rock and Virtue.

- Cans Are King

Cans are leading the dollar share of the market, growing at 1.5 times the rate of bottles. Six-pack (11-13 ounce) cans are now the top share item with 29% of total cider sales. This is followed by six-pack (11-13 ounce) bottles and 4-pack (18-ounce) cans. (These figures do remove shares of Angry Orchard, which sells in bottles. Because Angry Orchard dominates 40% of the cider market, they skew the data.)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Bringing Sool to America

Disappointed to find so little premium Korean sool in the U.S., Kyungmoon Kim @kimsomm_ms (who helped open Jungsik restaurant in New York City). Sool is Korea’s all-alcoholic beverages. In January 2020, Kim, a master sommelier, launched KMS Imports, the first importer of Korean sool featuring a small selection from nine producers. Kim wants to establish sool and soju, a Korean version of vodka, as a major spirit category and teach Americans about Korea’s brewing and distilling traditions.

“I believe soju can follow in the footsteps of mezcal: Fifteen years ago, nobody knew mezcal,” Kim says. “You could only find the cheapest grade bottles with worms inside. Now, regardless of cuisine, you can find mezcal behind the bar, and people appreciate nuances in flavor profiles and regional production. Soju has its own unique story, and once people understand it, they will want to learn more.”

Check out the SevenFiftyDaily article for a fascinating history into Korea’s ancient brewing traditions.

Read more (SevenFiftyDaily)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Restaurants in Crisis

A new restaurant survey shows 1 in 6 restaurants have closed during the pandemic. And 40% of restaurants say that ”it is unlikely their restaurant will still be in business six months from now if there are no additional relief packages from the federal government,” according to the survey by the National Restaurant Association. The association called the results “startling” and asked Congress for more help.

“For an industry built on service and hospitality, the last six months have challenged the core understanding of our business,” said Tom Bené, president and CEO of the NRA, in a statement. “Across the board, from independent owners to multi-unit franchise operators, restaurants are losing money every month, and they continue to struggle to serve their communities and support their employees.”

The NRA also found consumer spending in restaurants is down an average of 34%, the good service industry lost $165 billion in revenue from March to July and 60% of restaurant owners say their restaurant’s operational costs are higher prior to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Read more (Nation’s Restaurant News)

- Published in Business

Harnessing Fermentation for Sustainability, Part 2 of Our Conversation with Johnny Drain

In the second piece to our two-part Q&A with fermentation guru Johnny Drain, he details some of his recent fermentation consulting projects, as well as how (and why) more chefs need to use fermentation to create a sustainable global food ecosystem.

Drain works as a consultant for restaurants around the world, like Akoko Restaurant in London. Pictured, Drain poses with the team at Akoko. Akoko serves West African cuisine like dawadawa (fermented African locust beans) with ogiri egosi (melon seeds), a dish that shares similarities to natto.

TFA: The Cub Cave, where you’re currently working for Cub restaurant, tell me about it.

JD: That’s my “perma-lance.” But unfortunately, last week, we announced the Cub restaurant won’t be reopening after COVID, post lockdown.

The Cub restaurant is part of the Mr Lyan Group. So Mr Lyan (Ryan Chetiyawardana), he’s sort of this brilliant guy who typically operates in this world of cocktails and drinks, but also had this restaurant at the inception of food and drink. And Cub was really made to examine the inception of food and drink. The menu there was really this free-flowing journey through food and drink. So sometimes you’d have just a drink as a course, sometimes a food and a drink. It was really trying to break down this idea of why, even in the very best restaurants, have a food menu and a drink menu and they’re very separated. It was examining that intersection but also examining this intersection between luxury and sustainability. Why do you have to typically sacrifice sustainability when you have luxury and why do you have to sacrifice luxury when you have sustainability? So part of my time there, I set up the Cub Cave which was this R and D space literally below the restaurant in the basement, and I worked with chefs and the bartenders to essentially use that food waste, one, and in a deeper way examine ways that if there was an ingredient the chefs and bartenders wanted to use but perhaps they knew there would be a lot of trim or a lot of waste from it, I would go in and use my science smarts and find a way to use that trim. Basically to maximize the flavor that we extract from that produce we bring it.

There’s a famous American scientist of the 20th century, Richard Feynman, and when he was talking about nanotechnology, things at the nanoscale which are things that are atomically slightly subatomic which was my focus when I was a chemist and physicist, he famously coined this term “There’s plenty of room at the bottom,” meaning that there were plenty more technological applications in chemistry and physics.I like to say “There’s plenty of room in the bottom when we look in our bins.” Often what we throw away, pardon my French, there’s still shitloads of flavor in much of the food that we throw away. And it’s such a crying shame. My real role working with people like Cub in the Cub Cave and a restaurant called SILO, which is the UK’s first zero waste restaurant, is to look at what we’re throwing away and see what flavors are left. Then, use science and fermentation techniques to extract all that delicious flavor. When we’re talking about flavor, we’re talking about all the hard work, passion and dedication that some farmer has put in, or with animal products, the life some animal has given up to provide this product. The shame is that, often in most restaurants and bars, we would throw away much of it. There is still lots of flavor in there and how do we extract that flavor? Typically using fermentation.

TFA: Tell me more about SILO. What are some of the sustainability goals there?

JD: SILO was founded by this incredible guy called Douglas McMaster. He won British Master Chef Jr. when he was like 20, worked in a few restaurants around the world, then he had this epiphany when he was out in Melbourne working with this guy Joost Bakker, this zero waste pioneer. Doug had this mad idea of setting up this restaurant that had no bin. Which is kind of haughty if you’ve ever worked in a restaurant, you know how critical the bin is in a functioning restaurant or bar. The bin gets used several times a day. But Doug’s idea was to have a restaurant without a bin.

He set up a pop-up in Melbourne, then set up a brick and mortar restaurant in London called SILO. Really, Doug’s goal there is to be completely zero waste. A lot of that revolves around setting up relationships with the suppliers so that, when they drop off food or wine, either they drop off some type of pallet that goes back to get refilled or they drop it off in containers that can somehow be upcycled into some other product.

My goal in the SILO ecosystem is, if they do ever have trim, food trim usually goes to a composter, which is a viable and valuable use of food waste. But it’s a degrading, devaluing of the product. My role is to go in before the food has to go to compost, compost should be the last resort, and basically ferment it.

So we take things like dairy buttermilk when the guys make butter and we make this buttermilk garum, which is this incredible, golden-colored umami balm of a liquid, tastes of like blue cheese and toasted nuts, a little bit of caramel notes in there. We make this buttermilk garum and that goes on. Essentially buttermilk is a product that doesn’t have that great of value. But by fermenting it, the buttermilk garum has much greater value pound for pound than even the cream that started that process of making the butter. So we’re adding value back to the food chain and creating this phenomenal flavor profile that guests at the restaurants, even most chefs, no one has ever tasted because it’s a product no one else is making. The buttermilk, it went onto this slow cooked, aged dairy cow dish, and it also went onto this dish with brined tomato with sheep’s curd garnished with smoked grape seed oil, buttermilk garum and flowers. So we’re creating these incredible flavor profiles that blow people’s mind with this buttermilk garum which was born out of this necessity. How do we, if we’re going to make garum butter, which Doug wanted to do, we’re going to have lots of buttermilk. For every kilo of butter you make, you end up with about a kilo of buttermilk. It was born out of necessity and out of necessity, we’re creating this phenomenal, incredible, mind-blowing tasting ingredient.

TFA: Research shows that by 2050, when the global population is expected to reach 10 billion, we won’t have enough food to feed the growing population. How is our modern food system going to need to adapt to sustain our growing population?

JD: I think the first thing to point out is it will have to adapt. The course the industrial agricultural complex is heading, it’s completely not sustainable. It’s been based on this model of artificially-synthesized chemical inputs and fertilizers. Post World War II that was a necessity. It was innovative and smart and produced incredible yields, but it’s created a situation where the quality of the soil globally has degraded rapidly because of this, and we need to find different ways to nurture soil and produce or yield curves will just drop off.

We need to find ways to nourish soils, nourish ecosystems and create more resilient ecosystems and move away from this modern agriculture. But modern agriculture has been the prevailing paradigm for the last 30, 40 years. Sustainability has to be one of those cornerstones of the way we move forward. Sustainability has to be a tenant in all parts of the food system. We’re talking about from seeds, to how we grow food to the restaurant side, how can we take the foods we use and process it in a more sustainable way. That comes down to consumers being more savvy. They need to ask “I’ve got some cabbages in my fridge that look a bit funky and are starting to smell a bit, how can I use those?” Fermentation is one of those ways.

This is why fermentation popped up in the history of mankind. It’s a way of preserving the glut of food you had in summer and early autumn over the winters. Or it was a way of preserving, let’s say, dairy milk products. Milk sours off in 3-4 days, pre-refrigeration times, how do you preserve the very valuable nutrition that’s present in dairy milk for longer than that? So people started making butter, they started making cheese.

We’re going to harness some of those fermentation techniques as a way to extend the shelf life of those products that we have access to.

TFA: MOLD magazine, tell me how that came about.

JD: MOLD magazine, the name is potentially a bit of misnomer because it’s not just focused on mold. Although the first edition was focused on the human microbiome. But MOLD started off as a website which was started by a woman, LinYee Yuan. She’s a native of Texas, but now lives in New York and she’s an industrial designer by background. LinYee set up MOLD as a website to explore basically that intersection of food and design and where those meet. Some people might think that’s a bit of a weird marriage. What does food have to do with design? But in terms of everything we eat and all the utensils that we use to eat and the spaces we eat from restaurants to cafes, how our food is grown and processed and how it makes its way from farm to table, there have been design decisions made in all of those things. This interaction between food and design is very rich. And there’s a very deep, profound overlap between those two.

LinYee wants to explore that. She set up the website and we were set up between a mutual friend at a seminar a few years ago. She was looking for someone to create a print version of the work she’d been doing with the website. We came up with the idea of MOLD magazine.

We basically had this idea we’d do six issues of MOLD magazine, we worked with this incredible designer, Matt Sam and Erica Ko, who are based in North America as well. It basically explores one theme every issue. We’ve explored seeds, the human microbiome, food waste. We really go deep and we explore it from all aspects of the food side, the design side. The visual language we use in MOLD is very rich, it’s led by these brilliant designers we work with. It’s created as this print magazine in this world where most media we consume is online and we really wanted to create an object that you would sit down and get to grips with and immerse yourself in the experience of reading. It’s a limited print run, approximately 3,000 of each issue. But we’ve won lots of pleasing claudettes for the work. We were mentioned in the New York Times as one to watch. And we’ve worked with lots of great people. Massami Batora and Dan Barber wrote an article for us, all these great chefs. The response in the food world and the design world and the food tech world has been very positive to the work we’re doing and the ideas we’re sharing.

One of our core principles is that we want to use MOLD to give a voice to people that often in these conversations don’t have a voice. We are passionate about giving a voice to people who are underrepresented, people of color, women, basically using MOLD as a vehicle to give underrepresented voices a voice within these very important conversations around the world of food.

TFA: You spent time at Noma, working in the Nordic Food Lab. Your focus was exploring whether you can age butter like you age cheese. What was your conclusion?

JD: How I ended up there was completely bonkers. I had just finished my PhD. At that point I had no kitchen experience. I started working in the restaurants starging, which is basically, in the chef world, a French word which is to go and work for free for a week or two. I had started emailing people at these high-falutin restaurants that had these R and D facilities. One of which was this thing called the Nordic Food Lab which, to a degree, has been airbrushed from the history of Noma because of various politics. It started off, it was on this beautiful, big, Dutch barge in front of the old restaurant, Noma 1.0, which you could sort of see from the dining room. It started off as this food lab and test kitchen, and it became this food lab, this not-for-profit thing. Its mission was to kind of research Nordic cuisine and really elevate and amplify the work that Noma had been doing and find ingredients that could then go back into its menu. Eventually they kind of separated, the point where I was working there, the food lab was still on the Dutch barge outside the restaurant. (The Nordic Food Lab is now part of Copenhagen University.)

It was this incredible opportunity to work at the food lab, at a time when Noma was No. 1, on the world’s 50 best restaurant list, two Michelin stars, seen widely for various reasons as the world’s best restaurant, doing incredible things. As this guy who had worked mostly in sciences labs, which are very different from kitchens, to then suddenly be thrust into this environment of a world’s best restaurant, anyone who hasn’t been lucky enough to go to Noma, it functions in this very eclectic, choreographed way. It’s kind of this cross between this sort of military operation and a beautiful ballet where everything works kind of seamlessly. It’s a very beautiful spectacle to see a restaurant working at such a high level. To witness that, to be a tiny cog of this body working side by side with the restaurant, was an incredible experience and very inspiring.

I think the food lab really was responsible for a number of really important things within restaurant culture in the last 5 or 10 years. Rene Redzepi, who has done wonderful things for not just Nordic food but the whole food industry, I saw him speak in person a few times and he’s this very inspiring guy, he has this very powerful way of leading people and an incredible vision.

To cut to the question “Can you age butter?” Yes, you can. Basically, you end up with something that tastes like blue cheese. So you have these fermentation processes, this breakdown of these lipids, these fat molecules, into what we call free fatty acids. They are basically what gives flavor to a 36-month aged parmesan, which we all know and love. If you do that to butter, if you age butter, you get some of those same flavor compounds, and they’re present in parmesan, in aged comte. If you do it at just the right level, you get these kind of aged, spicy notes of a blue cheese or a delicious aged parmesan.

Unfortunately, aged butter hasn’t taken off in a way I thought it might, but certainly people are aging butters in a way they were 10 years ago. Hopefully, my work has encouraged people to investigate that in some small way.

Check out the first part of our Q&A with Johnny Drain here. To find out more information about Drain, visit his personal Instagram and the Instagram of MOLD magazine.

- Published in Food & Flavor