Fermented Foods Reduce Stress

Researchers have made a breakthrough discovery in stress management: fermented food can change one’s mood.

Scientists from the University College Cork (UCC) APC Microbiome research center found consuming 2-3 servings of fermented foods a day – like sauerkraut, kefir, kimchi, kombucha, yogurt, etc. – improves mental health. Stress and depressive symptoms are reduced when regularly consuming fermented foods.

Their month-long study analyzed the effects of a psychobiotic diet on adults, while the control group was given general nutrition advice in line with the food pyramid. The psychobiotic diet is designed to target the gut microbiome. It includes fermented foods, fruit and vegetables high in prebiotic fibers, grains and legumes.

“Although the microbiome has been linked to stress and behavior previously, it was unclear if by feeding these microbes demonstrable effects could be seen,” said Professor John Cryan, one of the study’s lead authors, vice president for research and innovation at UCC, and a principal investigator at APC Microbiome. “Our study provides one of the first data in the interaction between diet, microbiota and feelings of stress and mood. Using microbiota targeted diets to positively modulate gut-brain communication holds possibilities for the reduction of stress and stress-associated disorders, but additional research is warranted to investigate underlying mechanisms.”

Researchers studied participants with relatively low fiber diets, measuring their perceived levels of stress before and after beginning the psychobiotic diet. Four weeks in, participants reported a strong decrease in perceived stress. Their sleep improved, too. Forty chemicals were affected by the change,

“These results highlight that dietary approaches can be used to reduce perceived stress in a human cohort. Using microbiota-targeted diets to positively modulate gut-brain communication holds possibilities for the reduction of stress and stress-associated disorders,” the study reads.

Cryan, in an article for The Telegraph, said: “The mechanisms underpinning the effect of diet on mental health are still not fully understood. But one explanation for this link could be via the relationship between our brain and our microbiome (the trillions of bacteria that live in our gut). Known as the gut-brain axis, this allows the brain and gut to be in constant communication with each other, allowing essential body functions such as digestion and appetite to happen.

“It also means that the emotional and cognitive centres in our brain are closely connected to our gut.”

He added: “The next time you’re feeling particularly stressed, perhaps you’ll want to think more carefully about what you plan on eating for lunch or dinner. Including more fibre and fermented foods for a few weeks may just help you feel a little less stressed out.”

The study was published in Molecular Psychiatrry.

Educating Consumers About Fermentation

Fermentation continues to top food trend lists, health movements and restaurant menus, influencing more curious consumers to buy fermented foods. But the average consumer remains fermentation clueless.

“Fermentation is a really complicated subject and we’re just reaching the tip of the iceberg at this point when it comes to the research,” says Jenna Mills, account manager at Eat Well Global, a food and nutrition consulting agency. “A complicated subject like this is loaded and I feel that individuals and consumer know just enough to be confused.”

Five food professionals shared their thoughts on how to educate consumers about fermentation during a panel at FERMENTATION 2022. Panelists included: Mills, Shannon Coleman (associate professor and state extension specialist at Iowa State University), Matt Lancor (CEO and founder of Kombuchade), and Kirsten Shockey (author, educator and co-founder of The Fermentation School and TFA Advisory Board member). Amelia Nielson-Stowell, editor at The Fermentation Association, moderated.

Simple Messaging

The panelists agreed fermentation brands need to stop overcomplicating fermentation to the consumer, focusing on simple communication strategies.

“I compare it to a small child asking where babies come from – a simple answer is enough,” says Shockey. “With fermentation, often, we’re ready to say that lactic acid bacteria come in and they’re eating carbohydrates and there are these metabolites and flavors involved. We’re ready to share all the details – and we’re met with a blank stare. People just often want to know what’s the difference between a pickle and a ferment.”

Shockey, who teaches at the women-run Fermentation School, says she’s felt pressure over the years to innovate her classes and teach new subjects. But, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic when more consumers focused on health and turned to fermentation, her most popular classes are still the basic fermentation 101.

In a TFA survey last year, 70% of fermentation producers said a greater understanding of fermentation and familiarity with the flavors associated with fermentation would foster increased consumption of fermented foods.

Kombuchade is taking a unique approach to that education component, focusing on kombucha as a recovery drink.

“I’m looking to make probiotics cool for athletes, much like Gatorade made electrolytes cool for athletes,” Lancor says. The science of food is typically a mechanical process: eat fats, carbohydrates and proteins for optimal energy and performance. “There’s actually a microbial fermentation process that’s helping to rebuild your muscles.”

Kombucha marketing is geared toward a yoga, enlightenment crowd, Lancor adds, only reaching a certain number of consumers. It doesn’t resonate with all consumers.

“The south side of Chicago guys that play on my rugby team, they were never going to grab that kombucha bottle off the shelf with that kind of messaging,” he says. “There wasn’t this message of probiotics can be used for performance or recovery or even understanding kombucha’s place within an athlete’s regimen.”

Communicating Science & Tradition

Fermented food brands are tasked with bridging the gap between science and consumer.

Consumers keep informed about food and nutrition trends through professional associations (69%), academic (67%) and dietitians and nutritionists (62%), according to a consumer insights survey by Eat Well Global.

For 77% of consumers, the advice of dietitians and nutritionists impacts which foods they buy. Mills says healthcare professionals offer that counseling on how to incorporate fermented foods into the diet.

Don’t forget the ancestral wisdom, Shockey points out.

“My one liner is we’ve evolved with these foods and you are here because your ancestors successfully fermented,” she says. Rather than educating that people should eat a tablespoon of sauerkraut a day to meet nutrition needs, “try to bring it into your world naturally.” Eat a mixture of ferments, with yogurt at breakfast or hot sauce at lunch and kimchi at dinner.

“We cannot put ferments into this box that must be eaten raw. That to me is a barrier. You should eat this in any way that feels right to you,” she says, adding ferments were traditionally eaten cooked in soups and stews. “But in our minds right now is the idea that we have to eat our probiotics raw. These foods have so many metabolites that are being created in production and they follow through in the cooking process.”

Challenges to Starting a Brand

Starting a fermentation brand can be an overwhelming task. Sandor Katz, fermentation author and educator, said in his keynote address at the FERMENTATION 2022 conference that education is a huge challenge for people launching new fermented products.

“They often end up putting a lot of their energy into educating consumers,” he says.

Coleman says state extension offices are an underutilized resource for new producers. Her office got into food preservation after noticing many Pinterest recipes that gave poor advice on food safety.

“Just about every extension program has some form of food preservation type of program that they are delivering to consumers and they want to help,” Coleman adds.

There are no universal standards for labeling, an obstacle for new producers.

“Labeling is such a sensitive issue because you can get into big trouble with the FDA,” Nielson-Stowell says, pointing out the U.S. Food & Drug Administration only has 12 approved health claims a brand can put on a label. “It also gets tricky putting ‘probiotic,’ ‘prebiotic’ or ‘postbiotic’ on a label. It’s not regulated and confusing to consumers.”

The International Scientific Association of Probiotics & Prebiotics (ISAPP) is pushing for -biotics to be a more protected term. According to ISAPP, only fermented food brands with a scientifically measured -biotic should but it in a label. Their health benefits must be documented. For example, yogurts often have defined probiotic strains on their labels.

Nielsen-Stowell recommends using “live cultures,” “live microbes” or “naturally fermented” instead. And make sure retailers know what that means.

“If you’re getting your set in store with a retailer, the retailer will be your biggest advocate. The retailer is going to be the one talking to the customers more than you. Educate them. Do they know why your product is better than your competitor’s product?” she adds.

Promoting Fermentation Innovation

Several obstacles prevent the innovation of fermented foods, from the lack of scientific research to a chasm between science and industry to improving the sustainability of traditional ferments.

A third of foods consumed worldwide are fermented, totalling 3,500 products. A group of European scientists is studying how those fermented foods can drive innovation in food systems.

“There’s not a clear way to improve the unique properties of traditional fermented foods using microbial organisms,” says Vittorio Capozzi, PhD, a researcher with the Institute of Sciences and Food Production (ISPA) in Italy. “We still need innovation in traditional fermented foods.”

Capozzi was one of the presenters at a side event during the October Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Science and Innovation forum. PIMENTO hosted the session. PIMENTO (which stands for “Promoting Innovation of ferMENted fOods”) launched last year in Europe, a project of the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST). PIMENTO aims “to place Europe at the spearhead of innovation on microbial foods” by promoting fermentation’s health, diversity and production. To achieve this goal, five working groups are structured around different fermentation topics. The groups are made up of both scientist and non-scientist fermentation experts studying and eventually implementing their findings.

Traditional ferments have “an important part of biodiversity that we cannot neglect,” Capozzi says. Fermentation provides new microbial-based solutions for a variety of foods, from plant-based ferments to alternative proteins. Innovations can improve nutrition and sensory qualities.

“In this way we are preserving biodiversity that has huge potential in biotechnology, science and innovation,” he says.

Ferments, he notes, can be protected. For example, a ferment produced in a specific geographical region (tequila in Mexico), a protected diversity, vegetable type, animal product or the human behavior used in production (Salers cheese in France).

“Fermented foods have been shaped through the centuries,” says Effie Tsakalidou, professor at the Agricultural University of Athens in Greece. “We have a lot of diversity.”

One of PIMENTO’s tasks is to create a database on European fermented foods. This list would include food types, production, consumption volume, technological parameters and legal status (like certifications).

Speaking on the health benefits and risks of fermented foods, Smilja Todorović, PhD, a professor at the Institute for Biological Research in Serbia, notes there’s a dearth of reputable, peer-reviewed studies on fermented foods.

“One of the very important things is to identify gaps in scientific evidence regarding benefits and risks,” she says.

The current studies on fermented foods are few and limited. Research does prove consuming fermented foods is correlated with overall mortality, decreased risk of diabetes, certain cancer types, high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases. Todorović says that’s not enough.

“Unfortunately, when we look at scientific evidence to claim health properties, we can see that there are insufficient evidence. So all we have is a growing scientific interest in fermented foods and their impact on human health. However, we need to move from promising results to scientific evidence,” he says.

PIMENTO’s working groups are cataloging fermented foods’ impact on the gastrointestinal symptom, allergies, immunity, bone health and neurological projects. They also plan for projects studying fermented foods bioactive compounds, vitamin production and functionality; and fermented foods use in personalized diets.

The lack of studies prevents innovations in the field. Antonio del Casale, co-founder and CEO of Microbion, an agro-industrial microbiology company, says there is a disconnect between the scientists studying fermented foods and fermented food producers. He calls it “a valley of death.” The research on fermented foods is low, but the development of commercial resources are increasing.

“The problem is how to avoid the limitations of developing the food in this sector,” he says.

Consumers: We’d Eat More Fermented Foods if Knew Health Benefits

The general public lacks knowledge of fermentation and does not understand the health benefits. Nearly 85% of respondents in a survey said they would consume more fermented foods if they knew more about fermentation’s health benefits.

The study illustrates much work is needed in educating consumers. Over 83% of respondents didn’t know the definition of fermentation and over 60% had limited knowledge of the microorganisms involved in fermentation. Most learned about fermented foods at school (31%), the internet (29%) or home (26%). And 72% said they felt safe consuming fermented foods.

Researchers from the University of Maribor in Slovenia studied how much people in the country know about fermentation. The results were eye-opening, especially since fermentation is more common in Europe. The study notes Slovenians commonly grow up eating local fermented foods, like sauerkraut, sour turnip and sour milk, especially in rural areas.

“Despite the fact that less than one fifth of the participants were familiar with the definition of fermentation and understood the process, almost one-third of the participants at least tried to ferment at home,” the study concludes. “Fermented foods should once again become part of the diet to improve overall health and reduce or postpone the onset of a variety of chronic diseases that plague us today.”

Read more (BMC Public Health)

Nourishing Microbiota With Fermented Foods

The gut microbiome and how fermented foods can nourish it topped the Washington Post headlines in September. The article shared highlights from the growing number of studies that suggest “these vast communities of microbes are the gateway to your health and well-being — and that one of the simplest and most powerful ways to shape and nurture them is through your diet.” Food (and environment and lifestyle behaviors) have a much larger impact on the gut microbiome than genetics.

The article by health reporter Anahad O’Conner says science proves diverse diets make diverse gut microbiomes. Lower rates of microbiome diversity is linked to chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

One way to increase that diversity is by eating fermented foods – the article points out yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha and kefir as excellent examples.

“The microbes in fermented foods, known as probiotics, produce vitamins, hormones and other nutrients. When you consume them, they can increase your gut microbiome diversity and boost your immune health, said Maria Marco, a professor of food science and technology who studies microbes and gut health at the University of California, Davis.”

A study by researchers at Stanford – and published last year in the journal Cell – found people who eat fermented food regularly increase their gut microbial diversity and lower their levels of inflammation.

“While it’s clear that eating lots of fiber is good for your microbiome, research shows that eating the wrong foods can tip the balance in your gut in favor of disease-promoting microbes,” writes O’Connor. The “bad” microbes, according to research, are commonly found in highly processed foods “that are low in fiber and high in additives such as sugar, salt and artificial ingredients. This includes soft drinks, white bread and white pasta, processed meats and packaged snacks like cookies, candy bars and potato chips.

Tim Spector, professor of epidemiology at King’s College London and the founder of the British Gut Project, tells the Washington Post that eating a wide variety of plants, fiber and nutrient-dense foods is also beneficial for the gut. Spector encourages people to eat 30 different plant foods a week, which can include produce, nuts, herbs and spices.

Read more (The Washington Post)

Fermentation for Global Health

Though scientists and environmentalists have warned about the dangers of increased meat consumption, Americans’ appetite for it is not slowing down. The last three years marked the largest amount of meat produced on record.

“People know about the harms of industrial agriculture, but people eat more and more and more meat,” says Bruce Friedrich, CEO of the Good Food Institute (GFI). “It’s an inextricable rise despite more and more attention to the issues. The vast majority of people are just not going to apply ethical considerations to their food choices.”

Fermentation, Friedrich declares, can be part of the solution. “Fermentation can be so powerful for global health, climate and biodiversity,” he says.

Friedrich spoke at FERMENTATION 2022 on alternative protein innovation. GFI, a nonprofit, aims to accelerate the innovation of fermented, plant- and cell-based alternative meat. But the young, rapidly-growing alt protein industry faces major obstacles in scaling, regulation, pricing and consumer acceptance. Friedrich told a room of professional fermenters at the conference to consider shifting to a career in alternative proteins.

“Anyone involved in fermentation, you have the expertise in knowledge. It’s cross-applying the skills and interest in your professional life into this new field,” he says. “One of the significant barriers for all the companies doing this is talent, which is to say – you.”

Global Agriculture Crisis

Friedrich does not mince his words: we’re on the precipice of a major environmental and health crisis if we don’t reduce meat consumption.

Mass producing meat is “extraordinarily inefficient.” Huge amounts of crops are grown to feed livestock so humans can then eat the animals.. “We have been using an antiquated method to produce meat for 12,000 years,” Friedrich adds.

Internationally, 4 billion hectares of land are used for agriculture – 3 billion are for grazing livestock or to grow their food. It takes 9 calories of feed to produce 1 calorie of chicken; 40 calories to produce 1 calorie of beef.

“This is an incredibly inefficient way to try and feed the world,” Friedrich says.

And it’s getting worse. By 2050, global meat consumption is projected to increase – conservative estimates say 50%, while others go as high as 260%.

Animal agriculture also is thought to be a major contributor to global climate change and a major factor in deforestation. Livestock are pumped with antibiotics, creating resistance in humans that consume that meat.

Future of “Meat”

The answer isn’t necessarily a world of vegetarians – it’s to change traditional meat.

Friedrich compares the situation to renewable energy and electric vehicles. For decades, government leaders have preached reducing fossil fuel consumption. But, as populations have risen, so has energy consumption.

“You are not going to convince people to consume less energy,” he says. “What you need to do is replace fossil fuels with renewable energy.”

Similarly with meat, there cannot be a meatless world. “This is innovation focused, it is not about behavior change,” he says.

“GFI when we started, we were talking about disrupting animal agriculture. We very quickly realized our hope is to transform industrial animal agriculture,” he says. “Things will happen a lot more quickly if we have the major corporations on board.”

GFI is “enthusiastically working with the biggest companies in the world:” JBS, Tyson, Smithfield, Cargill and BRF, the five largest global meat producers.

The aim is not to regulate big agriculture or stop subsidies. GFI hopes to open access into the science behind alternative proteins, incentivize the private sector to continue R&D and encourage government funding.

“The same sort of cash breaks that allowed Tesla to be successful should apply to Nature’s Fynd and Impossible Foods and others if they want that money,” Friedrich says, listing two major companies in the alternative protein industry. “Our global battle cry is that governments should be funding alternative proteins.”

Food Trifecta

By not gatekeeping alt protein technology, Friedrich says GFI is helping perfect the process of giving consumers the exact same meat experience, but using plant- or cell-based meats. People want the food trifecta, Friedrich says: Is it delicious? Does it fill me up? Is it reasonably priced?

Fermentation is a booming sector in the alternative protein industry. It is split into three categories: traditional fermentation using lactic acid bacteria, yeasts or fungi; biomass fermentation which involves naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing microorganisms; and precision fermentation, which uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients.

Data from GFI found, of the alt protein startups utilizing fermentation, 45% use precision fermentation, 41% use biomass fermentation and the remaining 14% use traditional fermentation.

GFI recently hired two fermentation scientists, and their studies are already suggesting biomass and traditional fermentation will have better environmental numbers than plant-based meats. Fermentation is also a more powerful process than plant-based meat applications because fermentation can replicate precise fermentation proteins. And although traditional fermentation is the smallest part of the fermented alternative protein category, GFI sees it growing because of its ability to produce appealing flavors..

“Traditional fermentation can be an absolutely essential element to get meat to taste the same or better or cost the same or less,” he says.

“The plant based and fermentation products, they’re just getting started. The idea of competing with industrial animal meat has been around for (snaps his fingers) that long. The products are just going to improve and improve and improve.”

Does Organic vs. Conventional Matter for Fermented Foods?

Organic food is considered by some to be healthier and more nutritious than its conventional counterpart. But what about when that food is fermented? Does organic vs. conventional matter?

A new study reveals some surprising results: when it comes to fermented foods, “the quality of organic food is not always better than conventional food.”

Organic vs. conventional agricultural production is a hotly debated topic – some reports indicate organic food is more nutritious, but other research suggests the nutritional differences are not significant. Meanwhile, fermented foods are scientifically-proven to include higher nutritional value. “During fermentation, the concentration of many bioactive compounds increases, and the bioavailability of iron, vitamin C, beta carotene, or betaine is also improved,” the study notes. Fermented products also “inhibit the development of pathogens in the digestive tract.”

Researchers at the Bydgoszcz University of Science and Technology in Poland questioned whether fermenting organic food would change its nutritional output versus using conventional food. Their results were published in the journal Molecules.

Analyzing fermented plants (pickles, sauerkraut, beet and carrot juices) and dairy (yogurt, kefir and buttermilk), researchers measured the vitamins, minerals and lactic acid bacteria in the items. They compared using organic ingredients in one group to products made from conventional ingredients.

“Research results do not clearly indicate which production system–conventional or organic–provides higher levels of bioactive substances in fermented food,” the study reads.

Results were mixed. Lactic acid bacteria – the good, healthy kind – were higher in organic sauerkraut, carrot juice, yogurt and kefir. Organic kraut and pickles produced more vitamin C than conventional versions. And calcium levels were higher in yogurt made with organic milk.

But, interestingly, lactic acid bacteria levels were higher in conventional pickles and beet juice. Conventional beet juice also had five times more beta-carotene (vitamin A).

Read more (Molecules)

Cultured in Chicago: Highlights of FERMENTATION 2022

Science met the culinary arts in Chicago, at the first in-person conference of The Fermentation Association (TFA), FERMENTATION 2022. Over 200 food and beverage professionals from 15 countries Participated in four days of programming.

“There’s no denying that fermentation is having a moment – and that’s a wonderful thing that more and more people are aware of fermentation and interested in fermentation – but it’s really important to keep saying fermentation is not a fad, fermentation is a fact,” said Sandor Katz, fermentation author and educator.

Katz was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2022. The nearly 50 experts and thought leaders who presented included Dan Saladino (BBC journalist and author of Eating to Extinction), Kirsten Shockey (author, educator and co-founder of The Fermentation School), Bob Hutkins (food microbiology professor at University of Nebraska and founder of Synbiotic Health), Sharon Flynn (founder of The Fermentary in Melbourne, Australia), Bruce Friedrich (co-founder and executive director of The Good Food Institute), Maria Marco (food science professor at University of California, Davis) and Sean Brock (chef and owner of Nashville’s Audrey Restaurant).

The conference comes as sales of fermented foods and beverages continue to rise. Fermented products grew 7.1% in the last year, according to SPINS LLC, a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products that also presented at FERMENTATION 2022.

Though Katz taught his first fermentation workshop in 1998, he’s seen “a building interest in fermentation” in the last decade. Each year since 2011, “someone says the food trend of the year is fermentation.”

“Usually I end up being a cheerleader for fermentation, encouraging people who somehow think that fermentation is an alien process, that there’s something scary about it,” he said. “I mostly reassure people that they’ve been eating products of fermentation almost every day for their entire lives, that these are processes that their safety has been proven by their endurance over time. But you all don’t need to hear that. I am speaking to the converted here.”

Where Science Meets Industry

TFA aims to fill a niche in the world of fermentation. There are plenty of DIY fermentation festivals, food and beverage industry conferences and trade shows. But TFA connects science and industry.

Attendees at the event included an array of professionals involved in fermentation – producers, retailers, chefs, scientists, researchers, authors, suppliers, educators and regulators. The conference revolved around three tracks: food, flavor and culture; science and health; and business, legal and regulatory. The group of passionate fermenters in attendance uniformly expressed their excitement and delight to learn from experts in different disciplines.

“This unique conference had the most diverse attendees as it included chefs, scientists and more,” said Glory Bui, a graduate student researcher at the University of California, Davis. “It was nice to network with those who were and were not in academia to hear different perspectives in the fermentation industry.” [Bui won the student poster competition with her research on how fermented dairy products can affect gastrointestinal health.]

Producers made up over 40% of attendees and ran the gamut from small to large scale. Sash Sunday, founder and fermentationist behind OlyKraut in Olympia, Wash., said she’s been searching for such a fermentation conference since starting her brand in 2008.

“I really appreciate getting to spend time getting to know other fermenters, hearing about people’s creative processes and experiences in the field,” Sunday said. “I really loved all the tastings and spending time with people who really think about the flavors in fermented foods.”

Niccolo Fraschetti, owner of Alive Ferments, said networking was one of his favorite parts of the conference.

“There were people there that were superstars of fermentation to people making kimchi in the bathtub,” Fraschetti said. “It was such a cool merging of fermentation.”

Fraschetti officially launched Alive Ferments in March and said he never expected the brand to grow so fast, so quickly. Alive Ferments currently is sold in 25 stores in the San Diego area. At FERMENTATION 2022, he brainstormed ideas with attendees and speakers.

“Usually I feel like in these situations, everyone is tight-lipped and doesn’t want to share (business secrets),” he said. “But everyone was a really embracing community and willing to share their knowledge. There was no competition between the peers that were at the conference.”

Connecting with others in the industry was a highlight, too, for Suzette Smith, founder of Garden Goddess Ferments and Pick up the Beet in Arizona.

“I loved that like minds were able to come together sharing similar passions,” Smith said. (I also loved “learning what’s new in the promotion of fermented foods.”

Gregory Smith, an independent chef based in Pittsburgh, said he “drove back from Chicago with my mind racing about all the things I learned.” He said the various chefs who spoke at the conference – like Flynn, Brock, Ismail Samad of Wake Robin Foods, Jessica Alonzo of Native Ferments, Misti Norris of Petra and the Beast and Jeremy Kean of Brassica Kitchen – inspired him to dive into upcycling.

“I’m excited about the way they made me look at food waste in the kitchen space and how to help utilize waste and taking excess product and converting it into something tasty,” said Smith, who runs his independent culinary service Thyme, Love & Culture with friend Romeo Kihumbu.

Karen Wang Diggs, founder of the ChouAmi fermentation device, spoke at the event in a session on fermenting with medicinal plants. She said it was “an honor” to speak at FERMENTATION 2022.

“I got to hang out with a bunch of really cool, ‘cultured,’ fermenting people – and the presentations were fabulous,” she said.

Added Neal Vitale, executive director of The Fermentation Association: “It was a privilege to have a stellar lineup of speakers. It was great to get to get together at last and explore so many aspects of fermentation.”

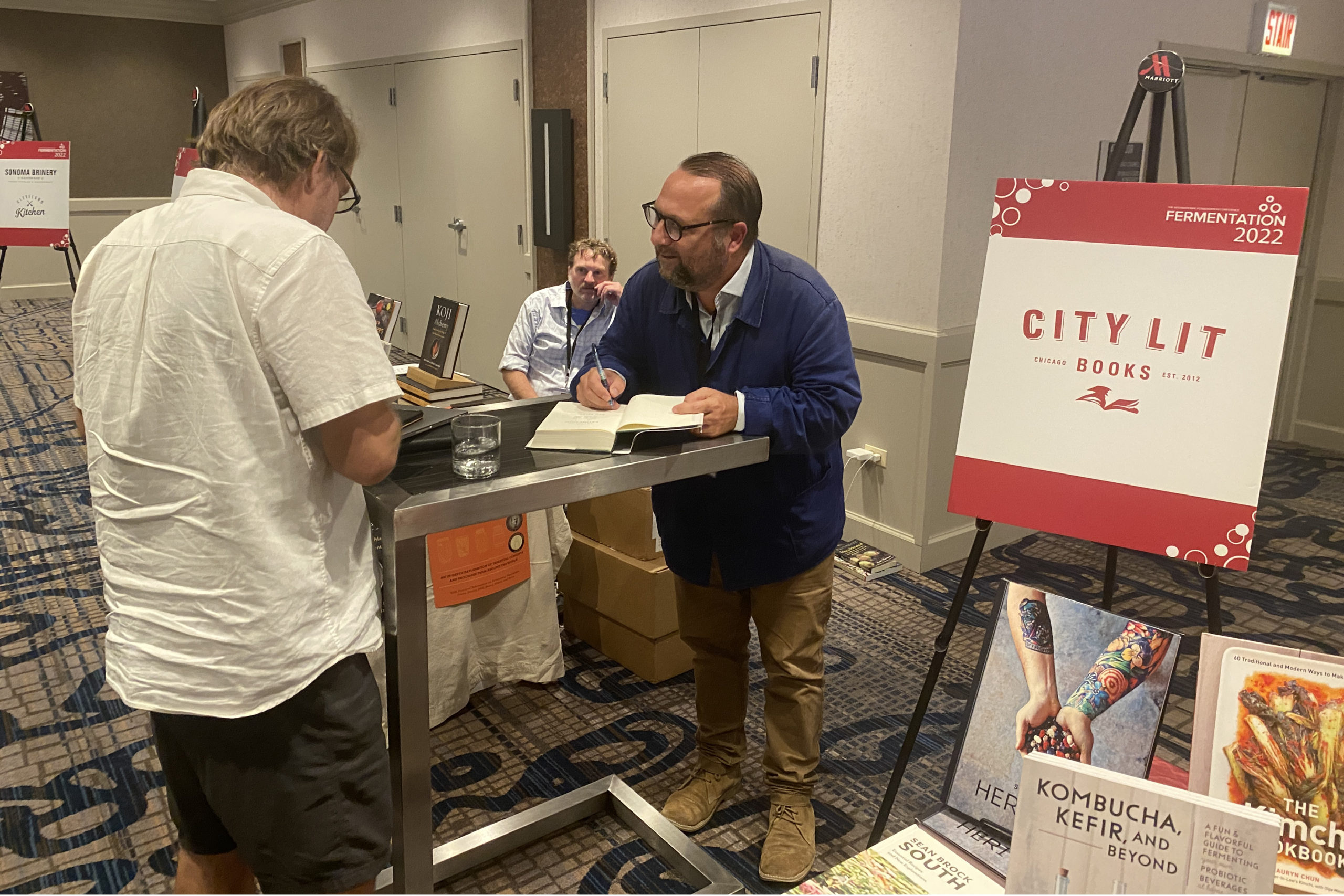

Focus on Food

Other events at the conference included: a dinner with a fermentation-focused menu prepared by Rick Bayless, chef and restaurateur; a mezcal tasting with Lou Bank, founder of SACRED and the Agave Road Trip podcast; a craft beer and chocolate pairing with Long Beach Beer, Bread and Spirits Lab; a flavor analysis workshop with Sensory Spectrum Inc.; a screening of Ed Lee’s film Fermented (complete with buttered popcorn!); and multiple book signings.

Bayless, the James Beard Award winner who runs multiple Chicago restaurants, mingled with conference attendees during the dinner. He said he and his staff enjoyed the challenge of putting something fermented in every course.

“This is the first time we’ve done a meal that is so heavily fermented,” he said, “and we had a lot of fun doing it.”

Courses included a fermented corn masa tamal, beed with a fermented black bean sauce made with black bean miso and Oaxacan pasilla chile, smoked yellowfin tuna in a broth of tejuino (fermented corn drink), and chocolate from Tabasco, Mexico, with tepache (fermented pineapple) sorbet .

“I was at a conference with Sandor Katz years ago and I talked to him about making black bean miso, and now I get to serve it to him,” Bayless said.

The Fermentation Association was started in 2017 as the brainchild ofJohn Gray, then the owner of Bubbies Pickles. His goal was simple – to bring together everyone in the world of fermentation. Today, TFA circulates its biweekly newsletter to nearly 14,000, is followed by over 11,000 on Instagram and will next develop its presence on LinkedIn. The Association is run by a small staff and a 22-member Advisory Board, including six Science Advisors.

FERMENTATION 2022 was originally planned to be a May 2020 event, but obviously postponed due to Covid-19. A virtual FERMENTATION 2021 was held in November 2021. TFA will announce plans for 2023 and beyond in the coming months.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Harnessing the Power of the Microbiome

A team of nearly three dozen researchers from around the world reviewed case studies on microbiome research in agrifood systems. Their results, published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology, “showcase the importance of microbiome research in advancing the agrifood system.”

Their 14 success stories include a broad range of topics within agrifood:

- Microbial dynamics in food fermentation

- Using microorganisms as soil fertilizers

- Applications to improve HACCP systems

- Identification of novel probiotics and prebiotics to prevent disease

- Using microbiomes of fermented foods for starter cultures

- Fermenting feed to improve the microbiomes of livestock

- Identifying microbes in fermented meats

- Using microbiota analysis for fermented dairy products

To further microbiome use in food systems, the research points to studies highlighting that fermented foods include many health-promoting metabolites (including studies by TFA Science Advisory Board member Maria Marco, a University of California, Davis, food science professor). But, the researchers stressed: “How certain microorganisms drive food fermentation, are transferred across the food production chain, persist in the final product and, potentially, colonize the human gut is poorly understood.” Researchers conclude that more work is needed to understand how the probiotics and metabolites in fermented foods could be used to treat diseases.

“Agrifood companies recognize the potential in understanding the microbiome and translating this knowledge into products,” the study continues. The food industry, the study notes, is “further preparing to develop personalized diets and specific foods for particular target groups in order to prevent or treat certain chronic conditions.”

“The microbiomes of soil, plants and animals are pivotal for ensuring human and environmental health. Research and innovation on microbiomes in the agrifood system are constantly advancing, and a better understanding of these microbiomes will be a key factor in producing highly nutritious, affordable, safe and sustainable food.”

Read more (Frontiers in Microbiology)

Infants Sleep More if Mom Eats Fermented Foods

Toddlers and infants slept 10 hours or more a night if their mother ate fermented foods while pregnant, according to a new Japanese study.

The results, published in the journal BMC Public Health, studied over 64,000 pairs of mothers and their children. The diet of pregnant mothers was found to have an impact on sleep length of their children. Pregnant women who consumed miso, yogurt, cheese and/or natto all had children that slept 10+ hours a night until the age of 3. The article calls it “fermentation for hibernation.”

The study notes, though, that there are other associated factors at play. The women consuming fermented foods were well-educated, employed and had higher incomes compared to the pregnant mothers not regularly consuming fermented foods. Scientists inferred that this higher demographic group “likely recognized factors that could contribute to health and chose nutrient-rich options [instead of] nutritionally-unbalanced food.”

Read more (NutraIngredients)