Japanese Cheese

Using local microbes, sakura blossoms, sake and takesumi (bamboo charcoal), chef and microbiologist Chiyo Shibata wants to “introduce Japan through cheese.” She runs cheesery Fromage Sen in mountainous Chiba Prefecture east of Tokyo.

Shibata fell in love with cheese — not a part of a traditional Japanese diet — while visiting France as a child. She later studied microbiology and fermentation at Tokyo University, then apprenticed to cheesemakers in France. When she returned to Japan to work at a government food safety lab, cheesemaking became her side hobby. Asked to analyze the safety of dried fish maker Koshida Shouten’s 50-year-old brine, Shibata made an interesting discovery. Not only was it safe, but the brine was teaming with lactobacilli. Inspired by the world of microbes, Shibata used a sample of brine as the foundation for her Japanese cheese.

“These microbes are the way to realize the terroir unique to this place and convey the message that this is our own cheese,” she says. She opened her rural cheesery in 2014 and has since won multiple honors, including Japan Cheese and World Cheese awards. Her handcrafted cheese, made with local ingredients, is aged 2-4 weeks. “Each ingredient is good on its own, but when you bring them together, they draw out their strengths and become something even more beautiful.”

Interestingly, Eric C. Rath, a professor of Japanese history at the University of Kansas, says cheese was never traditional fare in Japan because grazing cows on the country’s rocky terrain is difficult. But ancient texts describe three things similar to cheese: so, raku and daigo. Daigo was described as “the epitome of dairy products. Buddhist monks compared its taste to enlightenment,” Rath said. It’s unknown how these dairy products were made.

Read more (Atlas Obscura)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Regulating Home Chefs

The loosely-regulated cottage food industry is growing, as home chefs find it easier than ever to sell handmade meals via online services like WoodSpoon and Shef. These companies are part of the gig economy and trust that chefs will apply for the proper state and local permits to sell food made in a home kitchen. But these apps do not police regulatory compliance, noting only 20-30% of their chefs are licensed.

“In recent months, states have loosened restrictions to make it easier for home cooks to sell products online, but the result is a patchwork of state and local rules, regulations and permit requirements,” reads an article in The New York Times. “Some states allow home cooks to sell only baked goods like bread, cookies or jellies. Others put caps on the amount of money home cooks can make. And other states require the use of licensed facilities, such as commercial kitchens.”

Adds Oren Saar, founder and the chief executive of WoodSpoon: “We are ahead of the regulators, but as long as I keep my customers safe and everything is healthy, there are no issues. We believe our home kitchens are safer than any restaurants.”

As the pandemic ebbs and Americans feel cooking burnout, companies are investing tens of billions into the changing food industry. Alt protein, fast food, food delivery, functional snacks and alt food are all facets of a food industry growing and changing post-pandemic. The New York Times says they’re all making “bets on what, where and how consumers will eat in the coming years.”

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

China’s Secret Sauce

NPR highlights “Lu, the secret sauce at the heart of many Chinese family cuisines.” Every Chinese region uses a variation of Lu in their cuisine. It is made from a base of salty liquid (like soy sauce) mixed with sugar and spices. But salt is core to the product, more so than the spices.

Lu takes on “the characteristics of each of China’s regional cuisines.” In Sichuan, Lu is spicy; in Zao, it is alcoholic, made from the fermented rice left over from brewing Chinese yellow wine.

One Chinese restaurant chef (pictured, who asked NPR to keep him anonymous so his restaurant stays out of the limelight) traces his Lu sauce to “an unbroken chain of sauces dating back to that first batch his mother made in the 1980s.” The chef takes his sauce at the end of each day and gives it “nutrients” – fresh spices and meat boiled in Lu.

“It is a bit like sourdough, where the last batch seeds the next batch, and the flavor intensifies over the years,” the piece continues.

Read more (NPR)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Sandor Katz: “Don’t be Intimidated by Fermentation”

Further catapulting fermentation into the culinary zeitgeist: Sandor Katz was a guest on the Rachael Ray Show, talking about fermentation and sharing a homemade sauerkraut recipe.

“Everybody eats and drinks products of fermentation everyday,” Katz said on the show’s March 8 episode. “Fermentation, which is the transformation action of microorganisms, is so integral to how we make effective use of whatever food resources are available to us.”

Katz, author of six books on fermentation, stressed “bread is fermented, cheese is fermented, cured meats are fermented, condiments are either directly fermented or they rely on vinegar, which is a direct product of fermentation.”

Katz demonstrated how to make a sauerkraut for viewers, encouraging them: “Don’t be intimidated by fermentation.”

Read more (Rachael Ray Show)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Survey: Fermented Foods and Consumer Behavior

A new study aims to profile consumer habits with fermented foods and beverages. Researchers want to know the types of fermented products that are most popular — and why. To TFA’s knowledge, this is the first major study probing consumer perceptions of fermented foods.

“With this survey we hope to gain a better understanding of the types of fermented foods people are consuming and what motivates them to incorporate fermented foods into their diet,” says Erin DiCaprio, PhD, a food safety expert and extension specialist at UC Davis. “We also want to gather data on the trends related to in-home fermentation and the sources of information the public turns to related to fermented foods. The data we collect will help inform future areas of focus for research and education on fermented foods.”

The study is conducted by the EATLAC project at the University of California, Davis, Department of Food Science and Technology. EATLAC (Evaluating And Testing Lacto-ferments Across the Country), funded by California’s agricultural department, aims to provide accurate information and resources to the public. EATLAC’s directors are DiCaprio and Maria Marco, PhD, microbiologist and professor in the department of food science and technology at the university (and member of TFA’s Advisory Board).

To participate in the 10-minute anonymous survey, follow the link: https://ucdavis.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_0CzKfHUWgX2HHVj

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

“Consumers Have Changed” — State of Natural & Organic Industry

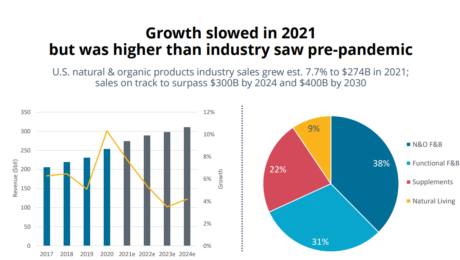

After the pandemic pantry stock-up of 2020, when grocery food purchases skyrocketed, sales of U.S. natural and organic products have slowed. Sales increased 7.7% to $274 billion in 2021. That’s a lower growth rate than the 13% pace seen at the height of the pandemic in 2020, but still higher than the pre-pandemic level of 5.3%. Sales are forecast to exceed $400 billion by 2030.

“For an industry that was always called a fad and a niche, to be able to hit $400 billion by 2030 just indicates that we have moved mainstream, ”said Carlotta Mast, senior vice president of the New Hope Network (a division of Informa PLC), which produces Natural Products Expo West. The stats were presented during the expo’s State of Natural & Organic Industry presentation.

Speaking to a standing-room only crowd, industry experts shared how the Covid-influenced sales boost will stay because “consumers have changed.”

“They’re paying more attention to their health and wellness, they’re investigating new brands, they’re cooking more at home and this is creating longer-term opportunities for this industry,” Mast said.

After a two-year hiatus, 2022 marked the return of Expo West, the largest natural products show.The event was smaller than in pre-pandemic times. There were 57,000 attendee registrations this year, versus 86,000 in 2019; 2,700 exhibitors, compared with 3,600.

Kathryn Peters, executive vice president at SPINS (a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products), said wellness-positioned brands are the main source of CPG growth and innovation. She cited that, while wellness products represent only 25% of the market, they produce 68% of growth.

“The pursuit of wellness is driving this industry and its changing consumers,” Peters said. “People are paying attention to what they’re putting in and on our bodies.”

Functional Flourishing

The natural, organic and functional food and beverage category — where fermented products reside — drives nearly 70% of natural product sales. Functional food and beverage sales grew 8.3% to $83.78 billion in 2021. Functional beverages, frozen foods and snacks are the top selling items in the functional space.

From kombucha to kraut, from chocolate to yogurt, dozens of fermented brands exhibited at this year’s event.

Esther Lee, CEO of Korean fermented tea brand IDO tea (a long-time participant in Expo West), doesn’t think it’s wellness attributes that initially attract consumers to functional beverages. She says it’s packaging and ingredients.

“Later on they usually realize their body feels different after using our products for weeks,” Lee said.. IDO Tea is currently sold in Korea, online on Amazon and in small shops in Los Angeles. It was at Expo West looking for a U.S. distributor.

New brand Miso Good attended the show as a relaunch. Founder Rhonda Cole began the woman-owned, start-up company with her daughter Lauren in 2019. The Florida-based brand then took a hiatus during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It has been difficult the past few years,” Cole said, adding she hopes to find success at the show. “Our motto is ‘ancient superfoods for the everyday eater’ and our fermented miso is great as a soup, sauce or condiment.”

It was the first Expo West for Local Culture Live Ferments, a Northern California brand that sells small batch sauerkraut, kimchi, hot sauce and brine tonic.

“We’re too small to be big, but too big to be small. We’re in this in-between stage and that’s very much why we’re here, to break through that threshold and get our product out to people,” said Chris Frost-McKee, director of operations. Local Culture was one of 40 brands selected by food distributor KeHe at their TrendFinder Event (read more about Local Culture in TFA’s Q&A). “We were maxing out our range with our current distribution. Our goal here was to open doors and make connections, and we’ve accomplished that.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Q&A with Local Culture

In a food industry where greenwashing is common, Local Culture Live Ferments doesn’t pad their sales sheets with faux environmental fluff. Sustainability is core to their business practices.

“I never want to stray away from the connections with our farmers. I never want to stray away from the quality of our ferments,” says Chris Frost-McKee, director of operations for the Northern California-based vegetable fermenter. Sauerkraut is their top seller. “We take a lot of pride from the fact that we don’t ferment in plastic. We are doing our part to be as plastic-free as possible and leave the smallest footprint that we can.”

The company began as a passion project of Chris’ sister, Sarah. She recruited her brother, a home fermenter since his early 20s, and they envisioned creating two Local Culture fermentation hubs on the west coast — one where Sarah lives, in Bend, Ore., and a second in Grass Valley, Calif., Chris’ home. True to their name, they wanted to ferment with local produce. But, with the colder climate in Central Oregon cutting Bend’s growing season short, this proved impossible.

“In Grass Valley, we’re able to source cabbage eight miles from our facility, eight months out of the year. We’ve created partnerships where every year the farm is planting more and more acreage for us, rotating their cover crops. It’s a beautiful thing, it’s real regenerative farming,” Chris says. And Sarah is now creating a separate project, fermented salad dressings, under the Super Belly Ferments brand.

Local Culture started as a farmers market side hustle, but Chris and his business partners (wife Cristina and friend Elissa Wolf Blank, pictured with Chris) dove into scaling the business in 2020. They’re now in over 100 grocers in the west, including Whole Foods. Though sales boomed during the pandemic, 2022 is shaping to be their biggest year. At the recent Expo West, Local Culture was one of 40 brands selected by food distributor KeHe for the exclusive “Golden Ticket” at their TrendFinder Event This designation fast-tracks small businesses into KeHe’s product portfolio, giving them exposure to over 30,000 retail locations.

Below is a Q&A with Chris Frost-McKee, who spoke with The Fermentation Association on the Expo West show floor.

TFA: Congrats on the KeHe “Golden Ticket” win! What are you going to have to change about scaling?

Chris Frost-McKee: The tricky thing with scaling the way that we do, our fermenters are stainless steel, variable capacity fermenters. We currently have 66 of them. We’ll need to get more as we scale, but they’re only sold once a year during wine making season. They ship them over from Italy. So that presents difficulties for sure. Producing in the same size fermenters, that’s part of the integrity we’re going to keep, that’s very important to me. We ferment for a minimum of 4-6 weeks in a very regulated, temperature-controlled environment. That really helps with the consistency of our product.

We are also keeping the values the same with our farmers, making sure they can scale while staying sustainable. We’re scaling up our acreage with our main farmer next year. They rotate three successions of a summer variety of cabbage for us and then one succession of winter storage. And with those four successions, we can work about eight months directly with them, never going into cold storage.

You just returned from a planning meeting with the local farm that supplies your cabbage. Tell me more about the farmers you work with.

CFM: We’re trying to only work farmer direct. One of our closest connections is the farm Super Tuber. They are Nevada City-based. They focus on regenerative farming practices and they focus on staple root crops and cabbage. So from the very beginning, as we first started with these smaller products, we started buying cabbage from them. Twice a year we sit down with them with the planting planning: What do you think it’s going to look like this year? How many plugs on your side can you plant for us?

Super Tuber is really into this idea and I love it — they harvest in reusable bins in the field, then bring them straight to us in reusable bins. When you work with farms, produce comes in paraffin or wax boxes. Those go straight in the landfill. We are trying to have as little waste as possible. We’d love to never receive anything in wax boxes, and we’re there about 95% of the time. We compost everything that comes out of the kitchen.

Another thing, the cabbage isn’t wrapped in plastic packaging. We peel off the outer cabbage leaves as we prep in the kitchen. Those outer leaves are what I like to layer on top to seal everything. It weighs the ferment batch down and provides a nice layer if there’s ever an impurity — which really doesn’t happen — so if we ever discard anything, it’s those top leaves that would normally get composted.

What was the biggest turning point for your brand to go from selling at farmer markets to getting in stores?

CFM: Honestly, as corporate as Whole Foods is, they have a wonderful way of supporting small brands. The west coast is filled with small ferment companies trying so hard and not succeeding at getting in. Whole Foods saw potential in us. That was really the turning point for our company. And they’ve continued to be loyal to us. Not all chains are pleasant to work with, but we made big moves through Whole Foods. It opened up this door to the Bay Area independents, like the Good Food Mercantile and the Good Food Awards. The Bay Area independents are so cutting edge in a way that I think a lot of these big chains strive to be as far as the products that they bring in and the diversity they really search for in craft products. At this point, we’re almost everywhere in the greater Bay Area that we’ve set out to be in — and I do think that started with getting in Whole Foods in 2020.

TFA: How were you distributing before that?

CFM: We were driving all over Northern California. We would drive five hours round trip to drop off like 10 cases of kraut. It did not make sense long term. Now we work with Tony’s Fine Foods to distribute to the pacific region. Tony’s has been supportive from the beginning.

We still self distribute locally, but only whatever we can do in a 20 minutes drive. The local support that we have, that started with our stands at the farmers market and then our storefront, that support has been amazing. Like we honestly sell more in our local co-op then we do in 40 stores in the Pacific Northwest. That kind of local support will always be there.

TFA: That’s great that you have a big local fan base.

CFM: When we decided to get going in Grass Valley, we opened up a store front for a year-and-a-half and had this really great interface with our community. We were really experimental in those years. That was the year I was coming up with a lot of small batches. When we were invited to be in the Whole Foods, we had to move to a distributor and palletize. Things were not so small batch anymore. Right as the pandemic hit, we started being received really well in the west coast. We streamlined the products that people really wanted. We’ve got our favorite line of krauts, our different kimchis. We still do a lot of hot sauces and brine tonics.

TFA: What is your favorite flavor?

CFM: Turmeric Ginger Jalapeno is my go-to, everyday. My body craves it. Our Beet Fennel though outsells anything we carry. People love it.

TFA: You’ve gone from fermenting in your home kitchen to distributing regionally. What do you think has been your biggest lesson in all of this?

CFM: Not giving up. Listening to the ferments — it sounds really weird, but I literally have studied patterns in the life within the fermenters. For example, we have these variable capacity lids that have an airlock on the top where the brine can spit out. In certain ebbs and flows, I think it’s astrological, all the fermenters will come to life, no matter how old they are. Or in a certain cycle of the moon, all of them will compact and leave an air pocket that I have to reset. It is crazy, witnessing the nature and patterns.

Through all the trial and error and discouragement, it’s the life of the microbiology itself that is really the inspiring thing. I could never get it right, it’s always going to be different no matter what. But I’m getting a lot better at creating that perfect environment for consistency. If you ask me — I’m living and breathing it because I digest this all the time.

TFA: Where do you see the future of fermentation?

CFM: I see it growing. It is beyond all the trends, it’s something that’s been around for ages, for centuries, and there’s a reason why it’s always been incorporated in our diets. There’s this sense of awakening that so many people in the mainstream are feeling — if it’s kombucha, if it’s sauerkraut, if it’s kefir, if it’s yogurt — people are really feeling the benefits. The pandemic has had a huge influence on that, too. I think everyone in grocery would agree fermentation is a big thing right now and it deserves to be a big thing.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Mexico’s Fermented Drinks

“Most people outside Mexico are familiar with the country’s tradition of distillates and beers. Far fewer have experienced an entire galaxy of beverages, like tejuino , that are much less available here in Southern California. They are made with Indigenous-based practices, typically inside people’s homes, usually with a plant, like corn, that’s already used for a bunch of other things in Mexico.”

A Los Angeles Times article highlights Mexican fermented drinks, like tepache, tejuino and pulque. They’re common in Mexico, brewed in home kitchens and sold at roadside stands. But in L.A. County where almost 4 million people trace their roots to Mexico, these rustic fermented beverages remain uncommercialized. Are Mexico’s artisanal, fermented drinks the last “importation of Mexican culinary practices to the United States?” the article speculates.

Tepache is the closest to breakthrough status in the U.S., with more companies offering canned versions. De La Calle Tepache was started by co-founder Rafael Martin using his grandmother’s recipe (he later studied fermentation in college). Ingredients in De La Calle Tepache are traditional to and sourced from Mexico. Martin describes his clientele as “chipsters” crowd – a slang term for Chicano hipsters.

Pulque, on the other hand, is difficult to replicate. The fermented aquamiel sap (from the core of the agave plant) only lasts two days before it starts to go bad. Some academics argue ferments from Mexico should be “more aggressively cataloged, preserved and consumed.” Scientists from the University of Arizona and four universities in Mexico recently published their research highlighting 16 of Mexico’s fermented beverages.

Read more (Los Angeles Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Experimenting with Yeast

The craft brewery industry is seeing increased innovation — and beer drinkers eagerly embrace these novel experiments. Brewers are turning to new, unique yeast profiles for distinctive drink styles.

“Whether a brewer chooses to ferment hot and quick or slow and cold is in large part a direct response to what microorganisms – i.e., yeasts – they select to turn their sugar water (aka wort, in beer-speak) into beer; and depending on the temperature and amount of yeast used, the same yeast profile can yield different flavors. Will a yeast profile influence the drinker’s experience?” reads an article in Sauce magazine. “The past several years have seen substantial innovation in the fermentation process leading to greater efficiency and efficacy.”

Yeast isolates used more and more by craft brewers include the lager-style Lutra kveik (kveik being the word for yeast in Norwegian). Kveik strains produce fruity, tropical-tasting beers. Another yeast rising in popularity among brewers is Sourvisiae, which produces a more sour flavor.

Read more (Sauce)

- Published in Food & Flavor

“The World Has Woken Up to Fermentation” — David Zilber

Big food companies are “eager to tap into the magic of fermentation,” says chef David Zilber. They’re hungry to hire culinary experts who can use fermentation to enhance existing products or mold the flavor profiles of new ones.

“These big companies are all waking up to the trend of fermentation and it is on us, on anyone who understands this craft intimately, to be the ones to engage them and guide them towards better solutions,” Zilber said at KojiCon. Fermenters could go the traditional route and open a local shop to feed a small number of people. But “there’s also a lot to be said for working within an existing system and fermenting the change you want to eat in the world. The biggest food producers in the world are responsible for nourishing most of mankind.”

The former head of the Noma fermentation lab, Zilber co-authored The Noma Guide to Fermentation with Noma’s founder Rene Redzepi. In the fall of 2020, Zilber surprised the food world when he left his job at Noma to join Chr. Hansen, a global supplier of bioscience ingredients.

Zilber said he understands the push-and-pull between working in traditional fermentation vs. large-scale food production. Though he cherished his time at Noma, he realized fine dining is “a minuscule fraction of the amount of food people eat” and, if he wanted to influence any big change in the food industry, he needed to move away from restaurants. He compared it to being “the punk rocker that rails against the system” when instead “subverting it from the inside is an amazing way to effect change extremely quickly.”

“When you learn to speak bacteria or when you learn to speak fungus, the hardcore food scientists don’t have this intuition,” he continues. “They grow these things in petri dishes and with colony pickers in €20,000 machines. It’s not the same thing, and we are a little bit at a watershed moment where there is enough community knowledge…that we can start to broach these players and try and change it.”

Streaming into KojiCon from his state-of-the-art kitchen at Chr. Hansen’s Copenhagen headquarters, Zilber shared his latest project: a tomato sauce for a client, improved through fermentation. In his kitchen, he works with chefs and food companies to use fermentation to develop healthier and more sustainable products. Holding up a sample of tomato sauce to the KojiCon attendees, Zilber shared how he was able to amplify the flavor profile of the canned tomato sauce using fermentation. He eliminated added white sugar and created a flavor with hints of parmesan cheese.

“We haven’t added anything but a culture onto it,” he said. “At the end of the day, should this tomato sauce go into production, millions of people overnight will be eating a tastier, probiotic (filled), more nutritious food on their pasta. And I never had to teach them how to lacto-ferment a single thing.”

Chr. Hansen is building one of the largest collections of cultures in the world, currently totalling 40,000 specimens. Zilber describes it as a seed bank, “the Noah’s Ark of Life for microbial diversity.” Chr. Hansen works with companies to select the optimal culture for their food item.

Smaller-scale producers, too, purchase cultures, often to mitigate risk. A fermentation mistake in a one-ton batch of kimchi could destroy thousands of dollars worth of product. Using a guaranteed culture strain will allow them to produce kimchi of consistent quality. But Zilber acknowledges there is no wild fermentation, no son-mat – a common phrase in Korean cooking that literally translates to “the taste of one’s hands.”

“There are aspects of the world of fermentation that are decidedly unwild, there are aspects of the world of fermentation that are nothing but wild,” he says.

Zilber believes we’re in the era of the democratization of fermentation, where books and educational courses are teaching the public about fermentation. He mentioned the new Sex and the City reboot featured a scene where a character was angry that sourdough challah was “too hipster.”

“It’s funny that it’s permeated public consciousness that much where we can now make jokes about it in multi-million-dollar, prime-time television shows. It means that the idea of fermentation in that respect has reached fixation. The world has woken up to this.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Science