An Irresistible Appeal

Scientists at Caltech , using fermented juice as bait have discovered that a fruit fly can travel six million times its body length in search of food.

Flies were lured by “a tantalizing cocktail of fermenting apple juice and champagne yeast produces carbon dioxide and ethanol, which are irresistible to a fruit fly.” Scientists released buckets of fruit flies on a dry lakebed in California’s Mojave Desert, far away from any other tempting food source.

The team is studying how far the flies would travel to a food source. Certain species of fruit flies are invasive and can cause significant agricultural damage. Their results will be published in the April issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Read more (Caltech)

- Published in Science

Fifth Time the Charm for KOMBUCHA Act?

For the fifth year in a row, the KOMBUCHA Act was reintroduced to Congress. If the legislation passes, kombucha beverages would be exempt from excise taxes intended for alcoholic beverages. The act proposes to raise the alcohol by volume (ABV) threshold for kombucha from its current level of 0.5% to 1.25%.

“The past year has been incredibly hard on businesses in Oregon and across the country, especially as supply chains have been disrupted. Still, kombucha is one the fastest growing beverage industries in the world,” says U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR). “There’s no reason why kombucha brewers and sellers should get taxed like beer. Our common sense legislation would eliminate this burden and support a burgeoning industry that has a major impact on Oregon’s food and beverage economy.”

U.S. retail sales of kombucha sales grew 2.4% over the twelve months though mid-July 2020, to $703.2 million, according to SPINS.

“Modernize Taxes & Regulations”

Blumenauer first introduced the bill in 2017 — and has reintroduced it every year since. Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), the Senate Finance Chair, is the bill’s co-sponsor.

The word “KOMBUCHA” also has a double meaning — it is an acronym for Keeping Our Manufacturers from Being Unfairly taxed while Championing Health Act. The legislators understand kombucha is a fast-growing beverage category, especially in their home state of Oregon, home to many kombucha brands.

“The growth of kombucha production in Oregon and nationwide creates jobs and a beverage folks enjoy,” Wyden said. “It’s been a particularly difficult year for small businesses, and our bill would modernize taxes and regulations so these businesses can continue to grow and sell their products in stores across the country.”

Kombucha Brewers Lobby

Commercial kombucha brewers are especially concerned with the regulation. In 2010, Whole Foods and other retailers pulled kombucha off shelves as the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau investigated whether alcohol levels in kombucha were higher than what was printed on the label. And since then, consumers — and even other brands — have filed lawsuits against various kombucha brands, alleging alcohol levels higher than indicated.

Kombucha can keep fermenting after it’s made, as the yeasts continue to eat sugars. Under current law, if kombucha leaves a processing facility at 0.4% ABV, but increases to over 0.5% by the time it’s placed on grocery store shelves, the brewer would have to pay federal alcohol taxes like a beer brand.

Hannah Crum, co-founder and president of Kombucha Brewers International (KBI), the trade organization for kombucha brewers, emphasizes that kombucha producers fear constant repercussions from the law.

“These numbers were created over 100 years ago during prohibition,” says Crum, and notes there are no scientific studies on these ABV values. “Kombucha labels say ‘Alcohol is present’ — no one is trying to trick the consumer.”

Reads a statement from KBI: “ These laws were never intended to make kombucha subject to taxes designated for beer. Passing the KOMBUCHA Act under the next appropriations bill will relieve this unnecessary burden on kombucha brewers. Only kombucha above that level (1.25%) will be subject to federal excise taxes when this Act becomes law.”

KBI has actively lobbied for the bill’s passage. Big kombucha brands (GT’s and Health-Ade) have supported the bill actively. KBI — for the first time — is asking consumers to write to their government representatives (via a form on their website) to urge them to support the bill.

- Published in Business

The Many Sides of Kefir

When Julie Smolyansky began working at her family’s Lifeway Foods business, her father advised her: “Don’t talk about the bacteria. People in America freak out about the bacteria on their food.” So when Lifeway became the first company in the U.S. to put “probiotic” on a label in 2003, it wasn’t a big surprise when customers began calling, asking for the company’s non-probiotic version of kefir.

Americans have come a long way. Consumers today search for the “live, cultured” label on fermented dairy, and gut health is a critical component of the modern diet. Smolyansky and Raquel Guajardo, author/educator, shared their thoughts on kefir during the TFA webinar The Many Sides of Kefir.

“Fermented foods were not part of the American diet, and the way that kefir and fermented foods in general were used in other parts of the world from Asian to Eastern Europe to even India and Mexico, these cultures all have fermented foods as one of their pillars as their foods sources and their health and wellness cultures,” Smolyansky says. “It wasn’t until immigration from all these other countries that we started talking about kimchi or kefir or lassi or you name your cultured kind of special food.”

In the U.S., the average person consumes 9-10 cups of fermented dairy a year. Contrast that statistic with Europe, where the average consumption is 28 cups a month.

“When you’re born consuming it and you’ve developed that taste palette, then it’s very easy to play in the space and have a diet that’s very rich in probiotics and kefir and all sorts of other fermented foods,” Smolyansky says, adding that the situation is changing in the U.S. Now, “people are hungry for it, they want it, once they learn about it, once they taste it, they fall in love with it, they’re hooked.”

Lifeway’s kefir’s sales have soared. The company was valued at $12 million when Smolyansky took over in 2002 — now it’s valued into the hundreds of millions. And even more customers have found kefir during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they adopt healthier lifestyles.

Guajardo has seen her online classes increase during COVID. The Mexico-based educator co-authored the book “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond” with Alex Lewin, TFA advisory board member, who moderated the webinar.

“People say ‘You’re crazy, why do you teach what to do at home what you can buy in the supermarket?’ But my business has been growing that way,” she says, adding that health benefits are the main selling point for her classes. “Why would people buy sauerkraut or kefir if you’re not explaining the benefits?”

Dairy Kefir vs. Water Kefir

Guajardo, who makes both dairy kefir and water kefir (also known as tibicos) stresses that the grains used to make each are “totally different.” Kefir grains are living bacteria and yeast microorganisms clumped together with milk proteins and sugars. They are gelatinous and white, almost like cottage cheese. Water kefir grains are also made from living bacteria and yeast microorganisms, but they’re clumped together with sugar and have a translucent, crystal-like appearance.

“Water kefir” is not the appropriate term, Guajardo and Smolyansky agree, instead calling it by its traditional Mexican name, tibicos. And they feel that using kefir or tibicos grains in coconut or almond milk and calling it kefir is also inappropriate. Smolyansky favors using a description like cultured coconut milk or beverage, but not kefir.

The National Dairy Council and Codex Alimentarius, the international food code, both state kefir is a fermented dairy product made from the milk of a lactating mammal. Smolyansky points to the many peer-reviewed studies on kefir, verifying it is full of probiotics and nutrients. Water kefir and non-dairy kefir have not been studied, and can’t guarantee the same health benefits.

“Just by throwing the name onto anything and just bastardizing the definition, we completely dilute any of the research that’s ever been done [on kefir], it would dilute the history, the folklore. So we are very passionate about protecting the name,” Smolyansky says. “My ancestors made sure that kefir survived for 2,000 years, and it’s critical that we don’t dilute it now that it’s having a moment, now that it’s popular.”

Smolyansky’s family emigrated to the United States from the then Soviet Union in the late ‘70s. Her father, Michael, began Lifeway Foods in Chicago in 1986.

“We have to respect the standards and what these definitions mean or it will be the Wild West and people won’t know what they’re buying,” she adds. She shares the labelling of ice cream as an example — ice cream is considered dairy while non-dairy products have other names, like sorbet, gelato or non-dairy frozen dessert.

Can Kefir Grow Like Yogurt?

Yogurt has paved the way for kefir to expand its consumer base in the U.S. Both are fermented dairy products with tangy tastes. But for kefir to achieve widespread, mainstream adoption like yogurt, significant education is needed. Thousands of peer-reviewed studies prove kefir contains a higher concentration of probiotics than yogurt — and a wider range of beneficial bacteria. For kefir to grow, this message needs to reach consumers.

“It’s a different set of microbes,” Lewin says. “Kefir is fermented with yeast and yogurt isn’t. Kefir has a larger family of microbes.”

Smolyansky is passionate that kefir cannot be compared to the products of the major. yogurt companies.

“The yogurt produced in the United States is so over-produced and so over-pasteurized that there’s practically nothing living in it after it’s been processed,” she says. “It’s one of the biggest problems with yogurt in the U.S.”

Lifeway regularly sends their products to be tested for probiotics, measuring Colony Forming Units (CFUs), the active microorganisms in a food product. Smolyansky says eating probiotics is critical in a germ-phobic, antibody-heavy society, where we’re over-sanitizing due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“If our bodies aren’t fighting an outside kind of pathogen, it starts to fight itself,” she says. “One of the ways to counteract this disruption in our microflora is by the use and the introduction of consistently replenishing microflora including diversity of bacteria, a variety of food sources that offer bacteria, the diversity and kind [of bacteria] is always the king. It makes for great food environments in the gut.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Wild Yeasts & Sour Beer

As sour beer becomes more popular, more producers are foregoing traditional kettle-sourcing processes to inoculate their brews with wild yeasts, often found in unusual places. Pennsylvania-based Levante Brewing Co. has developed a yeast called Philly Sour, which was found on the bark of a dogwood tree in a local cemetery and is now sold worldwide.

“I don’t know if the enthusiasm for hops will ever really wane, but with so many beer options available, there is definitely the space for some breweries to focus more on other ingredients,” said Gerard Olson, owner of Forest & Main Brewing Co. in Ambler, PA. That brewery every spring forages for yeasts from flowers on the property and uses them for that season’s saisons.

The Philadelphia Inquirer calls Philly Sour (and Norwegian yeast called kveik) “beer’s mostly unsung heroes.” The professor who isolated the Philly Sour yeast, “sends students into the neighborhood with Ziploc bags to collect samples, leaves, scrapings from bark, and other materials that might have yeast on them. Those materials are tested for fermentation.”

Read more (The Philadelphia Inquirer)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Solving Illnesses with Fermentation?

Scientists in Russia and Egypt have developed a functional drink that’s been proven to combat anemia and malnutrition. The juice is made from beet extract, milk and probiotic bacterial strains. The scientists developed a quinoa bread, too. The goal is to keep the beverage and bread affordably priced and get them offered at grocery stores internationally.

“One should bear in mind that we are not creating a medicine, but a natural, functional food product,” said Sobhi Ahmed Azab Al-Suhaimi, professor in the Department of Technology at South Ural State University (SUSU) in Russia. “However, this juice can make up for the lack of iron, zinc, manganese and calcium in the body. One serving of the drink will contain the whole rate [sic] of minerals. Its carbohydrate content is low. Fermented juice will help to overcome anemia and to improve digestion due to probiotics.”

Scientists at SUSU worked with scientists at the University of Alexandria in Egypt. Their findings were published in the Journal of Food Processing and Preservation and Plants.

Read more (Phys.org)

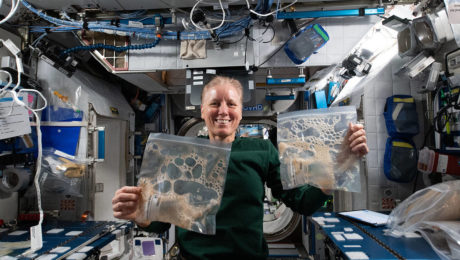

Fermenting — in Space?

Microbes that coexist on plants influence a crop’s size, shape, color, flavor and yield. What would these microbes do in microgravity? The International Space Station (ISS) is testing to find these results.

Flight engineer Shannon Walker (pictured) shows sample bags collected for the Grape Juice Fermentation in Microgravity Aboard ISS study. Astronauts will observe the fermentation process, measuring microbial differences. Back on earth, a matching, control sample is being observed in an environmental control chamber that mimics the ISS ambient temperature. The space and earth samples then will be analyzed for changes. Both flight and ground control samples are analyzed post-investigation for genetic change.

Read more (NASA)

Are Cider Clubs Worth it?

In the past decade, more cideries have begun clubs as a way to connect with their customers, keep year-round sales and sell rare ciders.

But during 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic closed taprooms and cancelled restaurant sales, cider clubs became critical to earn revenue. The American Cider Association (ACA) reported 22% of their members started a club in 2020.

“Our cider club was the one bright spot of 2020. That was really the one thing that kept growing, kept us motivated and got us excited,” says Talia Haykin, founder of Colorado-based Haykin Family Cider. Her products were sold in local fine dining establishments, but those sales evaporated during the pandemic.

“Everyone has kegs they can’t sell during the pandemic,” says Christopher Shockey, who co-authored the book The Big Book of Cider with wife Kirsten (a TFA Advisory Board member). “Cider clubs are keeping them afloat.”

Guaranteeing Sales & Creating Fans

Cider clubs are a subscription service where the cidery ships new, rare, seasonal or limited edition ciders to members multiple times a year. As both online shopping and access to direct-to-consumer alcohol shipping have expanded, subscriptions to cider, wine and other alcohol assortments have become feasible and increasingly popular.

“It’s taking customers who are already excited about you and converting them into a model that’s going to have them buy more from you regularly” says Eleanor Leger, founder of Eden Speciality Ciders. Leger and Haykin shared their tips on cider club growth opportunities during 2021 CiderCon.

“That’s money you know you’re going to have versus just duking it out on the store shelves where a new store manager can just decide they don’t want you and they want somebody else and you lose that shelf space,” Christopher says during the TFA webinar on “The State of the Art of Cidermaking.”

An ACA survey found that cider clubs generate up to 10% of a cidery’s total revenue.

Quarterly shipment of ciders is standard. Haykin and Leger advise cideries to ship more than twice a year, so members won’t forget they joined a club.

“You want to continually remind them that you exist,” Haykin says.

Shipping costs for cider — a fermented product which must be kept cold and is often sold in glass bottles — can be pricey. But, Haykin notes, even though he bears that high cost of shipping : “the repeat business of a club member is worth so much more to us.” Many clubs offer local pick-up to eliminate shipping costs.

Attracting & Keeping Customers

In the crowded alcohol market, cider clubs are a way to differentiate a brand.

While there are not specific stats on the demographics of Americans who subscribe to alcohol clubs, product subscription services overall are rapidly growing. Millennials are the dominant users of subscriptions — 31% currently have one or more, and another 38% say they will in the next six months.

Cider sales grew 9% in 2020, and they represent 11% of the craft beer category (where cider sales are tracked). Wine is struggling with Millenial and Gen Z consumers, who view it as a drink for an older demographic. Kirsten Shockey says younger consumers gravitate to cider instead.

“People are looking for funky flavors,” she adds. “I think the biggest battle cider makers have is feeling like the wine cooler crowd is their crowd. But that is changing, people are looking for more flavor.”

Member offerings vary for cider clubs, and can include:

- Discount on tap room products.

- First chance to try new items.

- Exclusive taproom tastings.

- Forage days (members help pick cider apples from local orchards).

- Volunteer opportunities at local farmers markets and food festivals.

The No. 1 reason people cancel a membership is because of a bad experience. Haykin stresses the importance of responding to a customer within, at most, 12 hours. “Communication is one of the most important things you’ll offer as a club,” she says.

Leger adds: “We jump all over someone who has had a problem to make sure they know we are sorry and we take care of it right away. Handling a problem really well creates incredible loyalty. People can be out there building your brand for you because they love you and they’re telling all their friends. If they have a bad experience, they’re destroying the brand for you.”

- Published in Business

“One Grain to Bind Them All”

A new study on kefir found that the individual dominant species of Lactobacillus bacteria in kefir grains cannot survive in milk on their own. The bacteria need one another to create the fermented dairy drink, “feeding on each other’s metabolites in the kefir culture.”

The research, conducted by EMBL (Europe’s laboratory for life and sciences) and Cambridge University’s Patil group and published in Nature Microbiology, illustrates a dynamic of microbes that had eluded scientists. Though scientists knew microorganisms live in communities and depend on each other to survive, “mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited,” according to a press release on the research.

“Cooperation allows them to do something they couldn’t do alone,” says Kiran Patil, group leader and author of the paper. “It is particularly fascinating how L. kefiranofaciens, which dominates the kefir community, uses kefir grains to bind together all other microbes that it needs to survive — much like the ruling ring of the Lord of the Rings. One grain to bind them all.”

To make kefir, it takes a team. A team of microbes.

The group studied 15 samples of kefir, one of the world’s oldest fermented food products. Below are highlights from a press release on the published results.

A Model of Microbial Interaction

Kefir first became popular centuries ago in Eastern Europe, Israel, and areas in and around Russia. It is composed of ‘grains’ that look like small pieces of cauliflower and have fermented in milk to produce a probiotic drink composed of bacteria and yeasts.

“People were storing milk in sheepskins and noticed these grains that emerged kept their milk from spoiling, so they could store it longer,” says Sonja Blasche, a postdoc in the Patil group and an author of the paper. “Because milk spoils fairly easily, finding a way to store it longer was of huge value.”

To make kefir, you need kefir grains, which must come from another batch of kefir. They cannot be made artificially. The grains are added to milk, to ferment and grow. Approximately 24 to 48 hours later (or, in the case of this research, 90 hours later), the kefir grains have consumed the available nutrients. The grains have grown in size and number, and are removed and added to fresh milk — to begin the process anew.

For scientists, kefir is more than just a healthy beverage: it’s an easy-to-culture model microbial community for studying metabolic interactions. And while kefir is quite similar to yogurt in many ways – both are fermented or cultured dairy products full of ‘probiotics’ – kefir’s microbial community is far larger, including not just bacterial cultures but also yeast.

A “Goldilocks Zone”

While scientists know that microorganisms often live in communities and depend on their fellow community members for survival, mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited. Laboratory models historically have been limited to two or three microbial species, so kefir offers – as Patil describes – a ‘Goldilocks zone’ of complexity that is not too small (around 40 species), yet not too unwieldy to study in detail.

Blasche started this research by gathering kefir samples from several sources. Though most were obtained in Germany, they may have originated elsewhere, grown from kefir grains passed down through the years..

“Our first step was to look at how the samples grow. Kefir microbial communities have many member species with individual growth patterns that adapt to their current environment. This means fast- and slow-growing species and some that alter their speed according to nutrient availability,” Blasche says. “This is not unique to the kefir community. However, the kefir community had a lot of lead time for coevolution to bring it to perfection, as they have stuck together for a long time already.”

Cooperation is key

Finding out the extent and nature of cooperation among kefir microbes was far from straightforward. Researchers combined a variety of state-of-the-art methods, such as metabolomics (studying metabolites’ chemical processes), transcriptomics (studying the genome-produced RNA transcripts) and mathematical modelling. These processes revealed not only key molecular interaction agents like amino acids, but also the contrasting species dynamics between grains and milk.

“The kefir grain acts as a base camp for the kefir community, from which community members colonise the milk in a complex yet organised and cooperative manner,” Patil says. “We see this phenomenon in kefir, and then we see it’s not limited to kefir. If you look at the whole world of microbiomes, cooperation is also a key to their structure and function.”

In fact, in another paper from Patil’s group (in collaboration with EMBL’s Bork group) in Nature Ecology and Evolution, scientists combined data from thousands of microbial communities across the globe – from in soil to in the human gut – to understand similar cooperative relationships. In this second paper, the researchers used advanced metabolic modelling to show that the co-occurring groups of bacteria, groups that are frequently found together in different habitats, are either highly competitive or highly cooperative. This stark polarization hadn’t been observed before, and sheds light on evolutionary processes that shape microbial ecosystems. While both competitive and cooperative communities are prevalent, the cooperators seem to be more successful in terms of higher abundance and occupying diverse habitats — stronger together!

Chocolate’s Beer Roots

Chocolate beer sounds like a faddish flavor, but its roots run deep. Pre-Columbian Mesoamericans fermented cacao fruit to make a beer-like drink called chicha.

“Chicha is usually made from corn, but there are regional variations made from other new-world plants like potatoes, peanuts and cacao beans,” reads an article from The Seattle Times. Chicha was studied by archaeology professors at Cornell and Berkeley who found “The roots of the modern chocolate industry can be traced back to this primitive fermented drink.”

Read more (The Seattle Times)

The New Definition of Fermented Food

After Dr. Bob Hutkins finished a presentation on fermented foods during a respected nutrition conference, the first audience question was from someone with a PhD in nutrition: “What are fermented foods?”

“I thought ‘Doesn’t everyone know what fermentation is?’ I realized, we do need a definition. Those of us that work in this field know what we’re talking about when we say fermented foods, but even people trained in foods do not understand this concept,” says Hutkins, a professor of food science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He presented The New Definition of Fermented Foods during a webinar with TFA.

Hutkins was part of a 13-member interdisciplinary panel of scientists that released a consensus definition on fermented foods. Their research, published this month in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, defines fermented foods as: “foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.”

“We needed a definition that conveyed this simple message of a raw food turning into a fermented food via microorganisms,” Hutkins says. “It brings some clarity to many of these issues that, frankly, people are confused about.”

David Ehreth, president and founder of Alexander Valley Gourmet, parent company of Sonoma Brinery (and a TFA Advisory Board member), agreed that an expert definition was necessary.

“As a producer, and having started this effort to put live culture products on the standard grocery shelf, I started doing it as a result of unique flavors that I could achieve through fermentation that weren’t present in acidified products,” Ehreth says. “Since many of us put this on our labels, we should be paying close attention to what these folks are doing, since they are the scientific backbone of our industry.”

Hutkins calls fermented foods “the original shelf-stable foods.” They’ve been used by humankind for over thousands of years, but have mushroomed in popularity in the last 15. Fermented foods check many boxes for hot food trends: artisanal, local, organic, natural, healthy, flavorful, sustainable, innovative, hip, funky, chic, cool and Instagram-worthy.

Nutrition, Hutkins hypothesizes, is a big driver of the public’s interest in fermentation. He noted that Today’s Dietitian has voted fermented foods a top superfood for the past four years.

Evidence to make bold claims about the health benefits of fermentation, though, is lacking. Hutkins says there is observational and epidemiological evidence. But randomized, human clinical trials — “the highest evidence one can rely on” — are few and small-scale for fermented foods.

Hutkins shared some research results. One study found that Korean elders who regularly consume kimchi harbor lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in their GI tract, providing compelling evidence that LAB survives digestion and reaches the gut. Another study of cultured dairy products, cheese, fermented vegetables, Asian fermented products and fermented drinks found that most contain over 10 million LAB per gram.

Still, the lack of credible studies is “a barrier we have to get past,” Hutkins says. There are confirmed health benefits with yogurt and kefir, but this research was funded by the dairy industry, a large trade group with significant resources.

“I think there’s enough evidence — most of it through these associated studies — to warrant this statement: fermented foods, including those that contain live microorganisms, should be included as part of a healthy diet.”