Craft Brewers Cater to Healthy, Active Lifestyle Drinkers

Craft brewers are catering to a new beer drinker: healthy, active lifestyle drinkers. Though craft brewers are thriving, it’s a smart adaption to add low calorie beers to their products. A study found 52 percent of beer drinkers want to reduce their alcohol consumption this year, the top reason being: “opting for healthier lifestyle.” Beer brands have often ignored the development of watery, light beers. But as millennials – who drove craft brewery growth – enter their 30s and focus on health and wellness, lower calorie beers are becoming an important part of breweries flavor lineup.

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Health

40% of Kefir Sales from Seniors

Seniors are driving the kefir market, a surprising industry stat since marketing of the fermented dairy drink is targeted at millennials. But new research from the Grocer found 40 percent of kefir sales in the UK were consumed by adults over the age of 65. People aged 16 to 44 accounted for 27.9 percent of kefir consumption. Analysts speculate its because kefir is likely to be consumed for particular health needs, which range from bone-strengthening nutrients to digestive aids, all factors people focus on as they age. “Add that the fermentation process makes it much easier to digest – because humans lose some of the ability to digest cows milk beyond age three – and even in the absence of multimillion-pound marketing budgets, the word of mouth marketing has spread like wildfire,” Bio-tiful Dairy founder Natasha Bowes.

Read more (The Grocer)

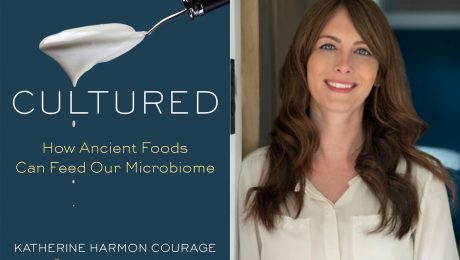

Q&A with Katherine Harmon Courage, Author of “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome”

When Katherine Harmon Courage began investigating the microbiome 10 years ago as a writer for Scientific American, gut health was barely a blip on the public’s radar. It’s hard to believe today. You can’t walk by a grocery store shelf without reading dozens of labels advertising probiotic health benefits.

Today, gut health is at the forefront of the food industry. The probiotics supplement market is estimated to grow at a CAGR of 9.7 percent in the next seven years. And the market for probiotic-rich fermented foods is expected to grow at a CAGR of 4.98 percent in the next five years.

Gut health research from scientists and dieticians surged in the past decade. Courage was fascinated. “Looking at the food around the world and the connection between our ancient diet and microbes, that is really, really exciting,” she says. Courage spent a year travelling the world, exploring the traditional, gut-friendly cuisine of different cultures. She paired her culinary investigation with modern science into an engaging book: “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome.”

Below, highlights from a Q&A with Courage on her new book, and her findings on the fermentation industry’s role in American’s evolving diets.

Q: You have been covering the microbiome since 2009. How has the scientific research progressed?

When I started covering it, there were small studies here and there, a lot from the Human Microbiome Project. Researchers were taking a census at the time, that we share our body with trillions of organisms. It was this niche area that I found super fascinating, but no one was talking about it much.

In the past decade, so much has changed. Science has evolved so much to learn about the connection between our health and our microbiome. We were raised to think germs are bad, bugs are bad, but we live with these commensal organisms.

Q: The food industry is taking notice of this research. What do you think of so many food products marketed with a gut health focus?

Talking to researchers, it’s interesting to see their perspective as scientists. They see the extreme of people thinking probiotics and microbes that are a marketing ploy to other people thinking probiotics and microbes will cure every health issue under the sun.

Microbiologists look at this critically. We’ve seen positive impacts on our health from it, but it won’t solve everything. We’re just at the beginning of understanding this relationship between these amazing and delicious fermented foods and our health.

Q: What’s the biggest misconception about microbes and our microbiome?

One of the misconceptions — and the one I had when I was thinking about this book — was the notion that if we eat something labeled probiotic, like a cup of yogurt, that we’re reinoculating our gut and restoring our gut health. Like if we eat a cup of yogurt, we’re good to go.

These microbes that we eat don’t stick around permanently. They’re just along for the ride. Weeks after we consume these, they’re not there anymore. When I learned this, I thought “There goes my research.” But when I looked into it more, in traditional culture and cuisines, people are eating fermented foods all the time, every day. It’s not about that one special food you eat or that one magic pill. It’s having those foods part of your daily cuisine and part of your life.

It’s great for fermentation producers. You don’t eat one jar of kimchi and call it good — you need to keep integrating it into your diet.

Q: Can a pill really fix our gut health?

Not being a scientist, I can’t say if it will or won’t fix our gut health. But talking to microbiologists who study this, it really is about exposing our bodies to these bacteria. We live our lives in such clean and pasteurized lives that we don’t get that microbial exposure. Their perspective is eating as many bugs, exposing ourselves to as many bugs, it will have a positive impact on our immune system as long as we’re healthy. A lot of the probiotic pills have been studied and they have positive health correlations, but we’re still learning so much about it.

Eating fermented foods, especially wild fermented foods, can be even more beneficial. Microbiologists and researchers in this field are really just starting to see what microbes are beneficial to our health. We can expose our bodies to more microbes through wild fermented foods because they’re so much more complex and have so many more microbes, rather than a yogurt with just three different microbes in it. We’re getting so much exposure through wild fermented foods.

Q: Why is it bad if we don’t properly feed our microbiome?

There’s the old friends hypothesis which is similar to the hygiene hypothesis. Our bodies have evolved to expect microbial exposure. But now our immune systems have gotten on this overactive trajectory, attacking these things they don’t need to.

We need to remember our native gut microbes, to feed them the nutrients they need to thrive. When we don’t feed our native microbes the fiber they need to thrive, they’ll eat the mucus lining in our gut, leading to more inflammation and asthma. We need to eat more microbes and feed the native microbes we do have.

Q: Can our native microbes change if we don’t feed them?

There’s been some interesting research out of Stanford’s Sonnenburg Lab. Mice fed on a diet with less fiber tend to have decreased microbiomes. Over generations, as the mice have pups, they pass that microbiome on to their pups. Generations later, these pups have super impoverished microbiomes. And they can’t come back and have a healthy microbiome by feeding them more fiber.

Q: Fermented foods are making waves in the food industry as the next big superfood. Tell me about fermented food in the book?

For the book, I got tor travel all over and explore these different cultures that have different fermented food traditions. I picked four main food places with quintessential fermented food — Greece to research yogurt, Korea to research kimchi, Japan to research miso and Switzerland to research cheese.

One of the cool discoveries I made travelling to these places was I discovered other aspects of the local diet that nourish the microbiome, other fermented foods and whole foods. These countries have different ways of thinking about eating than we do in America.

Q: What was the most eye-opening aspect of exploring other culture’s cuisine?

There were a couple. One, touring one of the big food markets in Seoul, Korea. Kimchi is their national food, but I was shown all these different fermented foods, different sauces, fermented soybean paste similar to miso, fermented veggies. It permeates their culture. Looking from far away in American grocery stores and farmers markets, you wouldn’t see it.

Second, in Japan, speaking with another author, we were talking about nato. Some people find nato challenging because it’s made with basic fermentation rather than acidic fermentation. The Japanese approach to fermented food, they teach at a very young age that “This is a wonderful, healthy food.” In America, we teach food as “Try this because it’s gratifying and yummy.” There’s this dichotomy of healthy foods versus gratifying goods. In Japan, there’s more of an understanding that there’s a wide variety of foods and you’re expected to eat all of them because that’s how you have a healthy life.

Q: Do you think this surge of fermented foods is a trend will disappear or a new food movement here to stay?

It’s here to stay. I expect to see it expanding and incorporating into more people’s lives. There is really compelling research with the health benefits, but there’s also these amazing flavors for those of us who weren’t raised with it. Like kimchi. Once you eat kimchi, food seems bland and lacking without it. Koreans describe it as “You need kimchi with every meal.” They can’t imagine eating it without. The flavor and texture experience is a big part of eating. We shouldn’t be forcing it down for our health, but truly enjoying it.

Q: Ancient foods are making an appearance in our diet again. Tell me what you found most fascinating in your research for this book on ancient foods.

One of the interesting things was how they are being incorporated into contemporary culture and cuisine. I went to a fermentation based restaurant in Tokyo, and I talked to the chef about how he’s integrating more traditional practices into contemporary cuisine and making very elegant meals out of them.

Q: Tell me more about your travels to Greece to learn about traditional yogurt. Modern yogurt is often criticized for the scientifically added probiotics. What did you find about traditional yogurt?

My image of yogurt was this fermented product with a few strains. But I wondered, with fermented yogurt products, are they just dumping strains in after they produced it?

Touring a family-owned, small-scale yogurt making facility in Greece, it was interesting seeing their process. They use backslopping, which is using part of the previous batch to inoculate the next batch. Traditionally, that was the way all of these products were made. It makes a richer microbial environment. We don’t know what strains are in it unless it’s sent off to a lab. Their strains come from the batch before and the batch before. Their yogurt would have strains unique to that product since they’ve made it for decades in that same place.

Q: Can better gut health help Americans notoriously destructive eating habits?

I think one of the keys is getting more fiber, especially prebiotic fiber from whole foods, not just a supplement, to really nourish a diverse gut microbiome. And, of course, eating more fermented foods.

For more information on Katherine Harmon Courage, visit her webpage. To purchase “Cultured,” visit Amazon.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Ozukè Founder: Fermentation Will Change Diet & Planet

Blending ancestral kitchen traditions and new scientific research will allow fermentation to change our diet — and our planet.

In a TEDx Talk, Mara King, co-founder of fermented food store Ozukè, shares why she is proudly releasing trillions of good bacteria into the population. Her food philosophy rubs against everything the Food and Drug Administration and state health departments practice. While government agencies enforce strict sanitation standards in the name of protecting American’s food, King preaches that it’s wiping out good bacteria and dumping more toxins into the environment.

When King and co-founder Willow King (no relation) opened their Colorado-based food business, a food scientist from the Denver office of the Health & Human Services Department performed a safety inspection. The food expert was confused by Ozukè’s live, fermented pickles, sauerkraut and kimchi. King: “He said ‘Your product is so weird. We follow all these FDA guidelines in food manufacturing in order to diminish bacteria and here you are making it on purpose.’”

“The food we make is actually super, super, super safe, unlike mots processed packaged fresh foods,” King says. “The reason this food is so safe is not because I’m better at this antimicrobial Macarena than anybody else. It’s because the bacteria are doing the work of making the fermented foods pretty much bomb proof.”

Though numerous cultures have been fermenting for generations (“It’s how humans have been eating raw, crunchy vegetables all through hard winters.”), King notes it’s only in the last 10 years that scientists have been able to map the complex fermentation process. By letting bacteria thrive in its own ecosystem, it “creates a food that’s no longer harmful to humans” and makes a more nutritious product.

“Nature does not operate in a vacuum and neither should we,” King says. “We need to understand the complexity of the world in which we live, then we can start to come up with solutions that do honor our heritage.”

King, who great up in Hong Kong, says older Chinese women store an impressive knowledge of food and medicine. Merging ancient tradition with new science is what will create the living solutions needed to continue living on our planet.

“In fermentation, we have a little trick that we use which is called using a started culture or a mother. I believe that our starter culture…is our human cultural history,” King says. “Once we start tapping this information…we’ll start to come up with amazing solutions, solutions that grow, solutions that rot, solutions that breath.”

Today Ozuke (which means “the best pickled things” in Japanese) still makes pickled veggies, but also teaches fermentation workshops. For more information, visit their webpage.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

Microbiologists Develop Healthy Kefir Formula

Microbiologists in Canada developed a formula that makes commercial kefir healthier. Traditional, old-world kefir is packed with health benefits, decreasing weight gain by 40% and cholesterol levels by 50%. Commercial kefir, though, does not contain bacteria-loving yeast used in traditional kefir. That variation in the fermentation process means commercial kefir is not as healthy. The Canadian microbiologist’s formula can be added to milk in commercial vats and is currently in the patent process.

Read more (Folio)

- Published in Health

Fermented Food Part of “Secret to Complexion Perfection”

Consider marketing fermented food and drink products as not just good for the gut but good for the skin. The New York Times calls the gut “the secret to complexion perfection,” and highlights the beauty benefits of a diet full of fermented foods. Though probiotics marketed specifically for skin health are selling out, doctors say supplements alone won’t help — diet is key. Carla Oates, known as the Beauty Chef, wrote a cookbook encouraging what she calls “gut weeding and seeding and feeding,” praising a diet of fermented foods like carob and sauerkraut.

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

Kimchi: the Fermented Flu Vaccine

Kimchi is a scientifically proven safeguard against the flu. New research proves, with fall flu season around the corner, we should stock up on kimchi. The fermented Korean food has an antiviral effect that stops the growth of the influenza virus. Flu-infected mice that ate kimchi had a higher survival rate and lost less weight. The study also referenced the 2003 SARS pandemic in Hong Kong and China — Korea was the only place where few people were infected with the virus, attributed to Korean’s love of kimchi. Study results were published in the Journal of Microbiology.

Read more (PR Newswire)

- Published in Health

Fermented Skincare Products Next Trend in Beauty Industry

Fermented, probiotic-rich foods are key to a flat belly and glowing skin, shares Elle magazine. But “Biofermentation is the next wave in the beauty industry,” adds the founder and CEO of Orveda. Fermented skincare products blend bacteria with fermented botanicals to work with the skin’s natural microflora. The magazine concludes: “a clean, calm gut will ensure your skin is lit from within and a fermented-rich routine will guarantee the glow won’t go.”

Read more (Elle Magazine)

Gov Support of Fermented Foods to Rise, Study Concludes

In the next decade, the British Medical Journal predicts we will see more government support of fermented foods. The BMJ’s latest research says the gov needs to fund the research and innovation of fermented products, prebiotics and probiotics. Food industry and consumer demands are shifting to healthier foods, so the BMJ says it’s critical for public leadership to also promote a healthy diet. The government can give tax incentives and push fiscal policies that promote “research, development and marketing of healthier foods in the food industry,” encourages the BMJ, and penalize companies that market sugar-laden drinks and junk food.

Read more (British Medical Journal) (Photo: Foodies Feed)

Getting Salty with Lauren Friel, who’s opening wine bar Rebel Rebel at Somerville’s Bow Market

Boston wine guru Lauren Friel says, to fix the local restaurant industry, health codes need to be revised. Friel says food regulations restrict chefs from using ferments and cured meats, making it especially difficult to serve authentic Chinese or European food.