Natural Production Changing the Wine Industry

Natural winemaking is moving mainstream, as more viticulturists preach the importance of soil health and shun traditional herbicides. “Where does natural wine finish and conventional wine start? These days, it’s hard to tell,” reads an article in Vinepair. Though the vast majority of global wine production still relies on conventional methods, the virtues of natural winemaking are helping change the industry.

“While it used to be rare for wines to be fermented with wild yeast — allowing the microbes present on the grapes to carry out fermentation — this is now much more common. And conventional producers have been prompted to question their use of additives such as sulfur dioxide. In fact, many aspects of winemaking that were championed by natural wine folk have now become much more common, even replacing some of the triumphs of more heavy-handed methods. As more producers trend away from making big, international-style reds with dark color, sweet fruit, high alcohol, and obvious new oak character, extracting less color and tannin for lighter-style reds is gaining popularity.”

Read more (Vinepair)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Noma Goes DTC

Noma is coming into the home kitchen.

The fermentation-focused restaurant, lauded as one of the top restaurants in the world, is selling its first line of packaged products. Two garums — vegan Smoked Mushroom and vegetarian Sweet Rice and Egg — will soon be available to ship internationally through the brand’s website, Noma Projects.

“It’s a space for us to channel our knowledge, our craft and experimentation into a new endeavor,” says René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant.

Redzepi shared details of the launch in a video on the site. Noma Projects will include pantry products and community-based initiatives, “a way for us to address issues we care about through the lens of food.”

Noma’s Pantry Staples

The garums are Noma’s “take on a 1,000-year-old recipe that we’ve been developing over the past two decades.” Redzepi says the “potent, umami-based sauces” have been the “key to our success at Noma in our vegetarian and vegan menus.

He hopes the garums will help more people cook plant-based meals, announcing in the video: “We want to help you bring more vegetables into your everyday cooking.” The garums provide the flavor of meat and fish without the animal. The website description notes: “Shifting towards a more plant-based diet is the easiest way for an individual to help the environment. We hope these garums will do the same for you that they’ve done for us, help inspire and create more delicious plant-based meals when you cook at home.”

These products were developed in Noma’s Fermentation Lab, where dozens of pantry staples were tested before landing on the garums. A garum is the “concentrated essence of its main ingredient” with a strong umami flavor, and Redzepi describes it to the WSJ. Magazine (the luxury magazine published by Wall Street Journal): “It has the potency of a soy sauce, except it tastes of what it is.” Both are brewed with koji rice, what Redzepi calls the “mother fungus.”

The garums are currently fermenting and will be ready for shipping in the fall or winter. The expected price point is $20-$35 for a bottle.

And more garums are in the works. Noma Fermentation Lab director, Jason Ignacio White, says a roasted chicken wing garum is next.

“It tastes like super chicken stock with umami,” White tells WSJ. Magazine, ”so it’s a familiar flavor, but there’s something about it that you can’t really put your finger on, that makes your tongue dance.”

Improving Profitability

Despite Noma’s expensive tabs — the 20-course tasting menu costs 2,800 Danish kroner (or around $447), and the wine pairing is another 1,800 Danish kroner (or around $287) — in the 18 years since it opened, the restaurant has hovered at only a 3% profit margin. Redzepi hopes Noma Projects will make more money. While it is “a family-run garage project,” its goal is to reach a million customers.

Like many restaurants around the world, Noma shut down during the pandemic. They reopened as a burger and wine bar in June 2020, and the walk-up, outdoor dining experience was such a success that it became a permanent restaurant, POPL.

Noma resumed regular operations on June 1, 2021. The pandemic closure allowed Redzepi and his team to finally tackle the retail brand, something he said they had debated for years.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Picturing Traditional Sake

Hoping to spur interest in traditional sake, a Japanese producer has published a picture book What is Sake? that takes readers on a tour of their sake facility. Suigei Brewing Co., based in the western city of Kochi, uses the book to detail how sake is made. The bilingual book includes English translations.

The president of Suigei Brewing Co., Hirokuni Okura, notes Japan’s sake culture is gradually being forgotten. He said he desires to “have both adults and children view sake, an element of Japanese food culture, as something close to them.”

The book’s illustrator, Misae Nagai, featured all 53 employees of Suigei in her charming illustrations.

Read more (The Mainichi)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

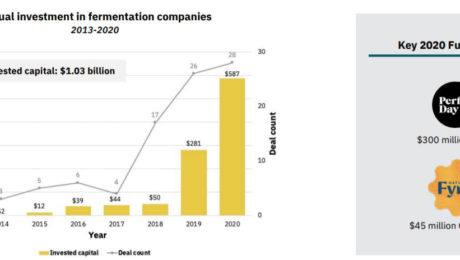

Fermentation for Alternative Proteins

Investments in alternative protein hit their highest level in 2020: $3.1 billion, double the amount invested from 2010-2019. Over $1 billion of that was in fermentation-powered protein alternatives.

It’s a time of huge growth for the industry — the alternative protein market is projected to reach $290 billion by 2035 — but it represents only a tiny segment of the larger meat and dairy industries.

Approximately 350 million metric tons of meat are produced globally every year. For reference, that’s about 1 million Volkswagen Beetles of meat a day. Meat consumption is expected to increase to 500 million metric tons by 2050 — but alternative proteins are expected to account for just 1 million.

“The world has a very large demand for meat and that meat demand is expected to go up,” says Zak Weston, foodservice and supply chain manager for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Weston shared details on fermented alternative proteins during the GFI presentation The State of the Industry: Fermentation for Alternative Proteins. “We think the solution lies in creating alternatives that are competitive with animal-based meat and dairy.”

Why is Alternative Protein Growing?

Animal meat is environmentally inefficient. It requires significant resources, from the amount of agricultural land needed to raise animals, to the fertilizers, pesticides and hormones used for feed, to the carbon emissions from the animals.

Globally, 83% of agricultural land is used to produce animal-based meat, dairy or eggs. Two-thirds of the global supply of protein comes from traditional animal protein.

The caloric conversion ratios — the calories it takes to grow an animal versus the calories that the animal provides when consumed — is extremely unbalanced. It takes 8 calories in to get 1 calorie out of a chicken, 11 calories to get 1 calorie out of a pig and 34 calories to get 1 calorie out of a cow. Alternative protein sources, on the other hand, have an average of a 1:1 calorie conversion. It takes years to grow animals but only hours to grow microbes.

“This is the underlying weakness in the animal protein system that leads to a lot of the negative externalities that we focus on and really need to be solved as part of our protein system,” Weston says. “We have to ameliorate these effects, we have to find ways to mitigate these risks and avoid some of these negative externalities associated with the way in which we currently produce industrialized animal proteins.”

What are Fermented Alternative Proteins?

Alternative proteins are either plant-based and fermented using microbes or cultivated directly from animal cells. Fermented proteins are made using one of three production types: traditional fermentation, biomass fermentation or precision fermentation.

“Fermentation is something familiar to most of us, it’s been used for thousands and thousands of years across a wide variety of cultures for a wide variety of foods,” Weston says, citing foods like cheese, bread, beer, wine and kimchi. “That indeed is one of the benefits for this technology, it’s relatively familiar and well known to a lot of different consumers globally.”

- Traditional fermentation refers to the ancient practice of using microbes in food. To make protein alternatives, this process uses “live microorganisms to modulate and process plant-derived ingredients.” Examples are fermenting soybeans for tempeh or Miyoko’s Creamery using lactic acid bacteria to make cheese.

- Biomass fermentation involves growing naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing organisms. Microorganisms like algae or fungi are often used. For example, Nature’s Fynd and Quorn …mycelium-based steak.

- Precision fermentation uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients. It is a type of biology that allows DNA sequences from a mammal to create alternative proteins. Examples are the heme protein in an Impossible Foods’ burger or the whey protein in Perfect Day’s vegan dairy products.

Despite fermentation’s roots in ancient food processing traditions, using it to create alternative proteins is a relatively new activity. About 80% of the new companies in the fermented alternative protein space have formed since 2015. New startups have focused on precision fermentation (45%) and biomass fermentation (41%). Traditional fermentation accounts for a smaller piece of the category (14%). There were more than 260 investors in the category in 2020 alone.

“It’s really coming onto the radar for a lot of folks in the food and beverage industry and within the alternative protein industry in a very big way, particularly over the past couple of years,” Weston says. “This is an area that the industry is paying attention too. They’re starting to modify working some of its products that have traditionally maybe been focused on dairy animal-based dairy substrates to work with plant protein substrates.”

Can Alternative Protein Help the Food System?

Fermentation has been so appealing, he adds, because “it’s a mature technology that’s been proven at different scales. It’s maybe different microbes or different processes, but there’s a proof of concept that gives us a reason to think that that there’s a lot of hope for this to be a viable technology that makes economic sense.”

GFI predicts more companies will experiment with a hybrid approach to fermented alternative proteins, using different production methods.

Though plant-based is still the more popular alternative protein source, plant-based meat has some barriers that fermentation resolves. Plant-based meat products can be dry, lacking the juiciness of meat; the flavor can be bean-like and leave an unpleasant aftertaste; and the texture can be off, either too compact or too mushy.

Fermented alternative proteins, though, have been more successful at mimicking a meat-like texture and imparting a robust flavor profile. Weston says taste, price, accessibility and convenience all drive consumer behavior — and fermented alternative proteins deliver in these regards.

And, compared to animal meat, alternative proteins are customizable and easily controlled from start to finish. Though the category is still in its early days, Weston sees improvements coming quickly in nutritional profiles, sensory attributes, shelf life, food safety and price points coming quickly.

“What excites us about the category is that we’ve seen a very strong consumer response, in spite of the fact that this is a very novel category for a lot of consumers,” Weston says. “We are fundamentally reassembling meat and dairy products from the ground up.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

“Magic Happens”

René Redzepi graced the pages of The New York Times again, but this time in the Arts section. The chef and owner at the world-famous restaurant Noma shared impressions on different musical pieces and other musings with writer Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim. One of his favorites: Mort Garson’s “Plantasia” (an electronic album meant for plants) that he plays in Noma’s greenhouse.

Redzepi also touched on fermentation. “It’s an antidote to the world where everything is so fast; on-demand; lightning speed. To actually have things that you have to wait for and then something magic happens, I love that. The happiest people I know are people who are in nature all the time: foragers, bakers, fermentation experts. Sometimes I envy that focus. My job is to be at the center of everything that is going on.”

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Korea’s Controversial Kimchi Book

As China and Korea continue to clash over where kimchi originated, the Korean government has published a book laying their claim.

“Kimchi in the Eyes of the World” contains history, recipes, stories from writers who love to eat kimchi, and how traditional Korean kimchi is different from China’s pao cai, a pickled vegetable dish.

The 148-page book was published by the Korean Culture and Information Service and the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. They plan to distribute it in Korean- and English-language versions through overseas Korean Culture Centers and via the foreign embassies in Korea.

Read more (The Korea Herald)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Advances in Yeast

We’re in the midst of a yeast revolution, as genome sequencing creates opportunity for cutting-edge advances in fermented foods and drinks. Yeast will be at the forefront of innovation in fermentation, for new flavors, better quality and more sustainability.

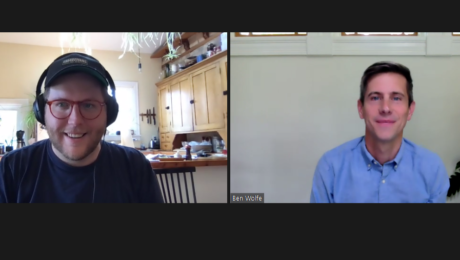

“Understanding and respecting tradition is a key part of this. These practices have been tested for hundreds and thousands of years and they cannot be dismissed. There’s a lot the science can learn from tradition,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University (and TFA Advisory Board member), during a TFA webinar, Advances in Yeast.

Preiss continues: “There’s still a place for innovation, despite such a long history of tradition with fermentation. A lot of the key advances in science are literally a result of people trying to make fermentation better.”

Wolfe, who uses fermented foods and other microbial communities to study microbiomes in his lab at Tufts, said “there’s this tradition versus technology conflict that can emerge.”

“I tell my students when I teach microbiology that much of the history of microbiology is food microbiology, it is actually food microbes, and they really drove the innovation of the field so it really all comes back to food and fermentation,” Wolfe says.

The technology relating to the yeasts used in fermentation has expanded enormously over the last decade, due heavily to advances in genome sequencing. Studying genetics allows labs like the ones Priess and Wolfe run to find the genetic blueprint of an organism and apply it to yeast. Drilling down further, they can tie genotype to phenotype to determine characteristics of a yeast strain. This rapidly expanding technology will disrupt and advance fermentation.

Priess predicted three areas of development for yeast fermentation in the coming years:

- Novelty Strains

Consumers have accelerated their acceptance of e-commerce during the Covid-19 pandemic and they’ll do the same for biotechnology, Priess says.

“Our industry does thrive on novelty,” he adds, noting there are beer brands already creating drinks with GMO yeast. “Craft beer is going to be the first food space where the use of GMOs is widespread — we’re seeing that play out a lot faster than I ever thought it would be with some of these products already on the market. Novelty does have value.”

Wolfe noted many consumers shudder at the idea of a GMO food or beverage, but microbes in beer are dead. Consumers are not drinking a living GMO in beer.

Yeasts also already pick up new genetic material naturally, through a process called gene transfer.

“It’s part of the evolutionary process that all microbes go through,” Wolfe says. “From my own lab and from other labs, cheese and sauerkraut and all these other fermented foods are showing so much genetic exchange that’s already happening.”

- Climate Change

The food industry must address growing concerns about climate change. Priess predicts breeding plants — like barley, hops and grapes — that are more drought-tolerant, or even using yeast technologies to increase yields or the rate of fermentation.

“Craft beer is massively wasteful,” Priess says. It takes between three to seven barrels of water to make one barrel of beer. “It is something we’re going to have to reckon with the next 10 years.”

Yogurt and cheese, too, produce large amounts of waste products.

- Ease of Genomics

The cost and time of genome sequencing has reduced significantly. It used to cost thousands of dollars and take many weeks to document a yeast genome. Now, it can be done for $200 in only a few days.

“The tools to deal with the data and get some meaning from it have never been more accessible. It’s incredibly powerful,” Priess says. “We’re developing solutions for products without millions of dollars.”

Priess does not agree with companies patenting yeasts, “it’s murky territory.” He believes fermentation and science should be about collaboration, not ownership and protection.

“Working with brewers and other fermentation enthusiasts, it’s this incredibly open and collaborative space compared to a lot of the industries,” he says. “I think that’s like our secret weapon or our secret value is that fermentation is so open in terms of access to knowledge as well as in terms of people being willing to experiment and try new things. That’s how it’s able to develop so quickly.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Surströmming – the Next International Craze?

A new Forbes article highlights surströmming, the fermented Baltic herring that’s a delicacy in Sweden. Considered one of the smelliest foods in the world, surströmming has become the darling of Sweden’s Disgusting Food Museum. The New Yorker recently published a piece on the museum, titled “The Gatekeepers Who Get to Decide What Food is Disgusting.” Manufacturer The Swedish Surströmming Supplier is promoting a surströmming challenge, encouraging people to post videos of themselves eating the fermented fish. The company says, once people “get past the initial shock of how it looks and smells when taken from the can,” many enjoy it. Surströmming is typically eaten with flatbread, potatoes, sour cream, chives and dill. (Forbes)

Read more (Forbes)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Fermentation Time Shapes Coffee Flavor

Adding to the growing research on fermentation and its impact on coffee’s flavor, food corp Nestlé released their own study on the link between coffee and fermentation. Scientists found that the length of time coffee cherries (or beans) are fermented is key to final flavor. They plan to use their findings to “tailor specific fermentation conditions to different coffee varieties, allowing us to highlight new distinct natural flavors and sensorial notes.”

“While several favors affect coffee quality, we showed a subtle combination of specific fermentation conditions can lead to a modulation of the sensory properties of the final cup, opening new avenues to differentiate coffee taste in a fully natural way,” said Cyril Moccand, a scientist at Nestlé Research who led the study.

On August 11, The Fermentation Association will host a webinar with the Specialty Coffee Association “The State of the Art in Coffee Fermentation.”

Read more (Beverage Daily)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Ancient Fermented Beans

The traditional Chinese recipe of fermented black soybeans known as dou si has made the pages of Saveur. Hetty McKinnon, a Chinese Australian cook and author, shares her mother’s penchant for flavoring dishes with these aromatic beans. Dou si is used in salad dressings and dishes like noodles, stews and stir-fries.

McKinnon writes: “Made from black soybeans that have been inoculated with mold, dou si is then salted and left to dry. Time — six months or so — imparts a robust, multi-dimensional flavor, reminiscent of other aged foods like parmesan cheese and olives. In my kitchen, the ingredient is a weeknight workhorse, and a quick way to add nuance and complexity to a meal with minimal effort and ingredients.”

Read more (Saveur)

- Published in Food & Flavor