To Be a Fermenter ‘You Have To Be a Bit of a Mad Scientist’

“Fermenting foods requires attention to detail and knowledge that not everyone has,” reads an article in the Greenfield Recorder in New England. The newspaper featured Jim Wallace, recipe developer at New England Cheesemaking Supply Co. Wallace says, to be a fermenter, “You have to be a bit of a mad scientist. (As) a mad scientist, you need to be answering questions.” In his home fermentation cellar, Wallace ferments wine, cheese, beer, kombucha and vegetables. He also teaches workshops, classes that have become more popular as more people tap into fermentation “a global food phenomenon — renewed interest in resurrecting forgotten food tradition.”

Read more (Greenfield Recorder)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Bubbling Over: Is Fermentation More Than a Fad

We asked three fermentation experts if recent popularity of fermented foods is a fading trend or a new food movement. These industry professionals weigh in on their predictions for fermentation’s future. The fermenters include Katherine Harmon Courage (author of “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome”), Aneta Lundquist (owner of 221 BC Kombucha) and Alex Lewin (author of “Real Food Fermentation” and “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond”)

Do you think the surge of fermented food and drinks is a trend will disappear or a new food movement here to stay?

Katherine Harmon Courage, author of “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome”: It’s here to stay. I expect to see it expanding and incorporating into more people’s lives. There is really compelling research with the health benefits, but there’s also these amazing flavors for those of us who weren’t raised with it. Like kimchi. Once you eat kimchi, food seems bland and lacking without it. Koreans describe it as “You need kimchi with every meal.” They can’t imagine eating it without. The flavor and texture experience is a big part of eating. We shouldn’t be forcing it down for our health, but truly enjoying it.

Aneta Lundquist, Owner 221 BC Kombucha: The future is fermented. Stretching back as far as human history itself, the origins of fermentation are hard to track down. People have been teaming up with microbes for much longer than we know. Almost every culture appears to have embraced fermentation for millennia but without a deeper understanding of it’s purpose. Fortunately for us, today’s science became “microbes-curios” and surprised us with some terrific findings. One of the most important ones is that we actually are ONE large thriving ecosystem and its survival is based on an ongoing symbiotic dance between microbial and human cells. Those cells communicate with each other and the outside world, exchange their DNAs and they even shape human behaviors. Now, in the 21st Century, we finally started embracing this profound partnership because of its obvious benefits (gut-brain connection, anti-inflammatory properties, digestive help, depression and Alzheimer aid… this list is almost endless). And there is no way back from here. Demand on fermenting foods is going to only grow from now on. As soon as so called “good microbes” from fermented food find a safe home in human guts, they will call for more of its kind. This is how “they” operate! Suddenly, people will crave kombucha, sauerkraut and kimchi-ferment generally. And that is exactly what we are observing now.

Alex Lewin, author of “Real Food Fermentation” and “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond”: Fermentation is not a new technology — in fact, it is one of our oldest! People have been doing it for millennia, and microbes have been doing it on their own since before humans even darkened the earth.

So by the numbers, it qualifies as a trend or movement.

But it’s definitely not a fad.

And to be fair, in some parts of the world, fermentation was never “out of fashion”. In Korea, for instance, kimchi has been a staple food for a very long time, often eaten with every meal.

My forecast for North America is that fermentation will continue to grow.

This is because fermentation is the meeting point of a few trends that are on the rise here:

– Health. We are more interested in health (and concerned about health) now than we have been at any time in recent memory. We are learning more about gut health and how it affects the rest of human physiology. Fermented foods are directly related to gut health.

– Food. North Americans watch more food TV than ever before, and celebrity chefs are as famous as pro athletes. People are eating things on a regular basis that their parents had never heard of.

– Sustainability/Infrastructure Resilience. Producing and preserving food without reliance on electricity and other infrastructure is an important thing that we as individuals can do to prepare for an uncertain future that will include climate change and may include dramatic societal change and partial or total infrastructure collapse.

- Published in Business

NYT: Does Kombucha Health Claims Live Up to Hype?

The New York Times asks: are there benefits to drinking kombucha? The article explores hard kombucha and the health claims of drinking the fermented tea. “But for those interested in integrating a variety of microbes into their diet, Dr. Emeran Mayer, author of ‘The Mind-Gut Connection,’ recommends doing so naturally. ‘I personally drink it occasionally,’ he said. Instead of using pills or supplements, he said, alternate different fermented foods, including sauerkraut, kimchi, cultured milk products, and, yes, kombucha.

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

Study Estimates Kombucha Grows to $5.13 Billion Industry in 2023

The global kombucha market is forecast to grow at a CAGR of 17% to $5.13 billion in 2023.

– HTF Market Intelligence

- Published in Business

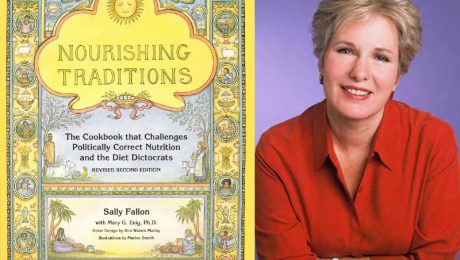

Sally Fallon Talks Fermentation

If just 10% of the population chooses to eat fermented foods, could the food industry be disrupted? Fermentation guru Sally Fallon says: absolutely.

“With fermented foods, you could get rid of all this huge medical industry selling you antacids and digestive aids, and this huge industry that’s grown up around IBS and celiac disease. We can destroy that industry by eating the right foods, and that means eating fermented foods,” Fallon says. The author of cookbook and nutrition guide “Nourishing Traditions” is often credited with bringing ancestral diet methods back into vogue.

Fallon, president of the Weston A. Price Foundation, founder of A Campaign for Real Milk and author of the new book “Nourishing Diets,” discussed fermentation during The Fermentation Summit. Below, selected highlights from Fallon’s interview with Paul Seelhorst, host of the summit.

Seelhorst: Tell us more about yourself and how you got into the fermentation topic.

Fallon: Well, when I was writing “Nourishing Traditions,” I wanted to make sure I was really describing traditional diets and not something people just think they are. I was very fortunate to find a book in French about fermented foods. I had never read about these before, lacto-fermented foods.

Recipes were very complicated – keep them at certain temperature for this many hours, then switch temperature for another few hours.

I kind of took this principle and worked out a way that was easy and fool-proof, using glass jars, we use way of innocuous so they don’t go bad while they’re starting to ferment.

Tried all these recipes, experiments, made children try – kids have funny stories about trying all these

The neat thing about fermentation is that it is a practice that’s traditional. When you ask traditional people why they do this, they wouldn’t know what to say or how to answer you, they just do it. But it totally accords to modern science. We have seen a complete paradigm shift in the last 20 years. In the past, bacteria were evil and they attacked us and made us sick. Now we realize that bacteria are our best friends, and we need at least 6 pounds of bacteria lining our guts in order to be healthy.

The way traditional people made sure that they had plenty of this good bacteria restocking everyday was to eat these raw fermented foods full of this healthy bacteria. They ate them in small amounts with the rest of their meals. This is how they did it, they had really healthy guts. We know when you have a healthy gut, everything goes better in life. You feel better, you digest better, you have more energy.

I recently wrote this book called “Nourishing Diets” which is about diets all over the world and what really struck me was the fermented foods. Every single culture in the world without exception eats fermented foods. Now some of these foods are pretty weird – like fermented seal flippers. Africa is the land of fermented foods. Almost everything they eat in traditional culture is fermented in Africa. They’ll kill an animals and ferment every part of the animal — the blood, the bones, the hoofs, the skin, the organ meats, the fat, the urine. Everything is fermented when they kill an animal.

Seelhorst: That’s pretty easy because its warm?

Fallon: Its warm, the bacteria like it. They have a saying – a rich man needs 10 animals to feed the wedding feast because he feeds everything fresh, but a poor man can feed the same feast with one animals because he ferments everything

Seelhorst: Do you know what they make out of urine, like a probiotic lemonade?

Fallon: I don’t know, they didn’t say. There’s two wonderful books on fermented foods – one is the “Handbook on Indigenous Fermented Foods” by Keith Steinkraus. He was at Cornell and is retired now. I fortunately talked to him while I was working on “Nourishing Traditions” and what he shows, he has a bunch of students from all over the world, especially Africa, and they do studies on the food. For example they take a food like cabbage and they’d measure the Vitamin c and the amino acids then they’d ferment it and measure it again. The vitamins goes way up – some 10-fold increase – and the amino acid increase.”

The other thing fermentation does with grains and meats, it releasees the minerals so they’re easily available.

There’s another wonderful book called “The Indigenous Fermented Foods of the Sudan: A Study in African Food and Nutrition.” The author was a student of Dr. Steinkraus. He reminds me a lot of Weston Price – he’s going to these traditional people not to, you know, lord over them and tell them how superior Western culture is. He goes with hat in hand saying “You guys have the secret here. You know how to eat; you know how to prepare food. Not only that, these foods can be done at the homestead, they can be taken to the market and sold, they are a good income for millions of people.” So he’s not pushing the industrial system, he’s pushing artisan food.” I just thought what a wonderful man, how humble. That’s how we need to come to these traditions – not how to make millions of dollars on them, but how to make a decent living for thousands of people and provide a healthy food for millions of people.”

Seelhorst: What I also like about fermentation is the sustainability aspect. People can make food sustainability and do not need fridges to keep the food good and not get it moldy.

Fallon: Foods like grains are impossible for humans to digest unless they are fermented. So many people can’t do grains, they’re sensitive to gluten. But when you ferment, as in the case of a sourdough bread or soaking your oats or pressed cakes all over the Southeast and Africa, these are fermented grains pressed into biscuits, this takes a food where most of the nutrients are unavailable to us and makes it readily available.

Seelhorst: Nowadays, people have fancy equipment to

ferment food. How did people ferment food back in the day?

Fallon: Usually they did it in large terracotta pots. And the culture was sort of in the holes of the pots, they didn’t have to add a culture, it was just hanging out there. When I started this in the late 1990s, this book I read in French was talking about these big pots. You couldn’t get these pots in the states when I was writing this book. I thought this isn’t going to work, the pots are heavy they’re expensive and they make a very large quantity which you may not be able to use. I thought we need a different method for the modern house wife or modern father. I thought “Let’s try to do this in Mason jars, the big quart jars with the wide top. Instead of having the culture hanging out in the holes, we didn’t have that. You had to add something in your culture, so that’s where we came up with adding whey. You have your cabbage or pickle or carrots or whatever it is you want to ferment, you put them in a bowl, you toss them with salt and a little bit of whey. You toss them, pound them a little bit, push them in the jar, push down heavily so the liquid comes and covers the top, this is an anerobic fermentation. Leave it at room temperature for a few days and its done.

Seelhorst: Where do people get the whey from?

Fallon: We teach people how to make it. You start with yogurt or with raw milk or something fermented like yogurt or kefir and you poor it through a fine cloth and the whey will drip out. From a quart of yogurt, you get about two and a half cups of whey. You’re only using a little bit at a time – a tablespoon or two – so that will keep a long time in the fridge. That’s your culture. There are other cultures, too. People are selling powders in culture. The only thing I would warn you is don’t try to do this without salt. Because the only time I heard about someone getting sick from fermented foods is when they didn’t use salt.

Seelhorst: Simply put – what happens during fermentation.

Fallon: What happens during fermentation is lactic acid is created by the fermentation. And in some foods, the lactic acid is already there. Like cabbage, cabbage juice is full of lactic acid. This makes whatever you’re fermenting get sour, it lowers the pH to under 4 and no pathogens can exist at a pH under 4. It makes the foods very safe and they don’t spoil after that. Lactic acid is a preservative just like alcohol is a preservative, but lactic acid doesn’t make you drunk. So, at the same time, these bacteria that are fermenting in there, they’re creating vitamins. Vitamin C, b vitamins. They’re breaking down what we call anti nutrients that block the simulation of minerals. They’re creating digestive enzymes that help you digest your food. The interesting thing is these bacteria and these enzymes do get through the stomach, they do get through and are passed into the small intestines where they are really useful. We’re not sure how that happens, they’re buffered in some way, but we do know these bacteria do get through

Seelhorst: How do you think fermented foods can fit into a modern diet.

Fallon: You can include them every day. One of my favorites foods is a fermented beet juice, I first noticed it in Germany, it’s called beet kvass. I have that every morning for breakfast. Sauerkraut is a really easy way, that’s the way most people do it, they just have sauerkraut with their meal. And then the fermented dairy foods like yogurt or kefir, those are wonderful fermented foods. You have a little bit with every meal.

Seelhorst: Are those the oldest fermented foods that we ate?

Fallon: In Europe, yes. We don’t have a tradition of eating fermented bones or fermented blood. But we definitely had fermented vegetables like sauerkraut, that dates to Roman times at least. And also fermented fish, the fish sauce, the universal seasoning, they found it in the ruins of Pompei where they were making it.

Seelhorst: What’s the difference between industrialized and self-made fermented food.

Fallon: once you industrialize something, they start to take shortcuts because they want to lower the cost. Typically, what they’ll do is eat something. So they’ll heat the sauerkraut and package it in plastic bags or something horrible or they’ll can it. So it will last forever and be shelf stable. Typically, the industry has not done genuine fermented foods because its not something that lends itself to an industrialized process. The things we consider true fermented foods in the united states, they’re being made by small companies.

Now the one exception to that might be yogurt. Yogurt is big business, it’s made by the big conglomerates. I would never even eat that yogurt because apparently the cultures are not even any good and the milk has been pasteurized.

Seelhorst: What’s your favorite fermented food.

Fallon: Kombucha. I make my own kombucha. I have a 30-day kombucha, I call it kombucha like fine champagne. It gets these tiny, tiny bubbles in it, it gets really, really sour and a little thick. I also make sauerkraut. It’s interesting – I’m a lot busier than I was when I wrote my book, I don’t have as much time as I used to have, but I still make my own fermented food. I do carrots and cabbage, I’m just about to pull some carrots and make some fermented cabbage.

I forgot to mention cheese. And cheese. Cheese is a fermented food. Here on our farm, we make cheese. I’d have to say cheese is my favorite fermented food. And also, traditionally made salami. A charcuterie is fermented. They hung these sausages up and fermented them. So they are fermented foods, they’re full of bacteria, good bacteria. They should be kind of sour, they’re very good for you.

Seelhorst: Do you want to add anything for people that just found the Fermentation Summit and may not know what fermentation is, they want to try it

Fallon: I will say this – you don’t have to make it yourself, there’s a lot available, in the states there’s now hundreds of artisan producers making sauerkraut. I love to see that – I love to seen an individual be able to start a little business without a big capital investment and make food that’s really good for people and make a decent living. Here on our farm, we have a store and we sell sauerkraut made by a Russian lady who has just made a wonderful living doing this. I love to see that. Just like artisan cheese. I love see small production of cheese; I love small production of fermented goods. Bread is another one, we now have a lot of artisan bread makers. This is the future of food – its sustainable food, its moral food, its food that makes you healthy, its good for the economy, it keeps the money in your community. I think people need to realize that every morsel of food they put in their mouth is a political act. It’s a decision they make. What are you going to support? Are you going to support Monsanto and Kraft and Unilever? These huge corporations who don’t care about you at all, all they care about is making a profit. Or are you going to support local artisan producers? People just like you making a decent living and providing a healthy food. And you’re also deciding whether you’re going to put something healthy or unhealthy in your body and in your children’s bodies. The traditional cultures, they had no choices in what they ate. They ate what was there, they ate according to their traditions. Today, we are not traditional people. We have left all that behind. We have to think what we eat, everything we eat is a choice. They didn’t have a choice, they just had healthy food. Now we always have this choice between healthy artisan food and unhealthy corporate food. So what kind of society do you want to live in?

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

Female Entrepreneurs Turning Western North Carolina Into “Ferment City”

Western North Carolina is becoming “a hot spot for fermented goods” thanks to female entrepreneurs. These fermented product brand leaders credit the health-conscious culture of Asheville, N.C. with helping their businesses thrive in “Ferment City.” Sara Schomber of the Buchi Mamas tells Asheville’s Mountain Xpress: “Fermentation is all about the alchemy of ingredients normally found in the hearth and home where, for centuries, women have been the keepers. We believe fermentation is the expression of a natural tendency, the human spirit’s way of giving itself permission to heal and inviting all of us to extend beyond our own immediate mortality. It’s normal and natural for humans to want to preserve, put away and celebrate.” Local brands featured include: Shanti Elixirs Jun, Smiling Hara Tempeh, Yoga Bucha kombucha, Buchi Kombucha, Sister of Mother Earth cider and honey, Serotonin ferments ferments and Fermenti Foods ferments.

Read more (Mountain Xpress) http://bit.ly/2B61p0Q

- Published in Business

More Brands Aim to Create Community Around Fermentation

More fermentation brands are creating ways to connect with their customers, face-to-face. Harvest Roots Ferments started in 2012 as a small farm in Birmingham, Ala. “At the time, Lindsay was fermenting kraut and kombucha for our farmers market table. Our customers wanted ferments way more than kale,” said Pete Halupka, who runs Harvest Roots Ferments with Lindsay Whiteaker. “About three of four years ago, we committed fully to fermentation. Now we produce kombucha, kraut, kimchi and other fermented vegetables and sell them across Alabama.” Now Harvest Roots Ferments is opening Birmingham’s first kombucha taproom. No longer traditional farmers (they source from local farmers, buying 75,000 pounds of produce since 2015), Harvest Roots Ferments is looking to build and connect to the Birmingham community that has helped their business grow. Halupka continues: “We love community in all forms—from the microbial community in action fermenting our products to the community found in our Southern forests and our human community across Birmingham—and we want our space to be a reflection of this.”

Read more (BHam Now)

- Published in Business

Q&A with Wild Kombucha, Baltimore-based, Cause-Driven Kombucha Brand

Baltimore-based Wild Kombucha has grown massively since their founding almost five years ago, increasing sales 466 percent in the last three years. The founders hard work and the drink’s delicious flavor helped propel the brand into 1,000 stores in eight states and Washington D.C.

At Natural Products Expo East, Wild Kombucha’s three co-founders point to another factor in their success: the city of Baltimore.

“A big piece was telling people we’re a local kombucha company, it’s Baltimore made,” says Sergio Malarin. “People here are super focused on local, they really love it. A lot of the initial accounts we worked with didn’t even bat an eye about bringing us in. Eddie’s Market, Charmington’s, One World Café, all the healthier, vegan and vegetarian independently-owned grocery stores and cafes, they brought us in and started selling us, fast.”

Co-founders Malarin, Adam Bufano and Sid Sharma are all first-generation Americans raised in Baltimore. The trio (Bufano and Malarin are step-brothers – Sharms is a childhood friend) take great pride in their hometown, praising the locals as a factor in Wild Kombucha’s success. They started selling under the Wild Kombucha label in February 2015 as a side gig, brewing in the evenings after their day jobs. They officially left their former careers for Wild Kombucha in August 2016, the day Whole Foods agreed to sell Wild Kombucha.

Today, Wild Kombucha employs 21 people and is brewing 10,000 bottles and 50 kegs of kombucha each week. They’ve moved to a 13,000-square-foot brewery and taproom in Baltimore. They will release their new flavor — a CBD kombucha flavor — in October.

“We’ve focused on how to educate the community around us on the health benefits of kombucha,” says Bufano. “So many people come to our demo tables and say ‘I don’t like kombucha, but then they try ours and they buy a bottle because it’s very approachable.”

Below is a Q&A with Bufano, Malarin and Sharma, who spoke with The Fermentation Association at their booth during Expo East.

Q: How did you start Wild Kombucha?

Bufano: Sergio and I are stepbrothers. Our family brewed kombucha when we were younger; our parents taught us when we were like 10 years old. And then I continued to brew from then basically until now, perfecting the recipe every time. I started selling it to my friends and then, at a certain point, I was trading it for rent. I was selling it to Hopkins students (John Hopkins University of Medicine). I had this big group of Hopkins students that would come to my house, grab a six-pack and bring me the empty bottles, I’d sanitize and refill them. And then I reached a point where I had to start charging people a little bit more to make it an actual business. That’s when Sergio and I hooked up and came up with a plan to expand and make it a little more legit. Sid is a childhood friend of ours, so we brought him on, too.

Q: You started with your parent’s kombucha recipe. Where did this kombucha recipe originate from?

Malarin: Our parents learned about fermented foods was from this woman, Sally Fallon, who wrote this famous book called “Nourishing Traditions.” She is a best-selling author, and my mom actually became one of her top volunteers and became friends with her.

Bufano: So we would make like sauerkraut, kefir…

Malarin: Water kefir, milk kefir, sourdough…

Bufano: And it went beyond fermentation. Our fridge was pretty crazy.

Q: Sounds like your parents were very health.

Malarin: Yes. They were super into fermented foods.

Bufano: And this was in the ‘90s, before it was cool.

Q: Where did your kombucha recipe originate from?

Bufano: My parents learned from Sally Fallon how to make it, but they really made it their own. I used their recipe, which wasn’t very good at that point, and improved it.

Q: What makes Wild

Kombucha unique?

Malarin: It’s a lot more approachable than other kombuchas. So the taste,

but also the package. Our mission is to make kombucha approachable and

available to everyone. So not necessarily the Whole Foods crowd, we want this

something the average joe in Baltimore can grab.

Sharma: It has a fresher flavor profile. So because of that, we also have lower sugar, so really the fruit comes out so you don’t need to add sugar after the fact.

Malarin: What really differentiates us as a company is we are one of the few cause-driven kombucha companies. We donate 1% of our sales to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation – that’s what makes us Wild Kombucha.

Q: Why did you decide on the Chesepeake Bay Foundation?

Malarin: Since we were kids, we’ve gone swimming on the Eastern Shore. For us, it’s super important. It’s where we live, it’s a huge ecosystem. We really feel our community goes beyond the people in it, it extends to the ecosystem and the wildlife as well.

Sharma: We want to put resources back into the place where we’re using the resources.

Malarin: For us it’s very important to be more than a bottom line. We want to be a business that gives back in many, many ways in the community. We are located in Northwest Baltimore, which is a bit of a food dessert. We opened a taproom out there and we’ve been hosting yoga classes there, we’ll do a speaker series soon. We want the community to be able to participate and be a part of wwat we’re doing.

Q: Tell me how important that was to be in Baltimore. You moved a few years ago from Baltimore to the suburbs, and now you’ve moved back to Baltimore.

Bufano: We tried to stay in Baltimore at that time, but in order for us to push ourselves forward, the only option for us was to move to this space that we found in the Timonium area outside of Baltimore. Just moving back into Baltimore was a huge thing for us. We’d been looking for a space for a while, anticipating our move back. We feel a connection here, we want to support the city. A lot of businesses are moving out of Baltimore, so Baltimore really needs support right now.

Q: Why does Baltimore need the support of local businesses like Wild Kombucha?

Malarin: Baltimore is getting a lot of negative attention in the media. From Freddie Gray and all the craziness that came out of that as well as just the stuff Trump has been saying, and there’s been a big focus on the violence. A lot of other big cities have a lot of negative things too, but you don’t hear people saying those things about, like Chicago. People say the sausages are good in Chicago, the jazz and blues music are good, but there are a lot of murders in Chicago, too. The media doesn’t focus solely on the negative in other cities like in Baltimore.

Sharma: There’s this unfortunate migration out of the city. And there’s a wealth gap, this poverty gap that exists within Baltimore. By employing people in the city, we’re able to make a difference there. By putting local products into the economy, we keep the dollars inside Baltimore as well. It’s about helping the people around us, helping the people who have supported us and allowed us to grow, and paying it forward.

Q: Your sales have skyrocketed since your start in 2015. How do you think you’ve grown so much?

Malarin: A lot of hands-on work on our part. We very much went out and met people and talked to people and shook hands and pounded the pavement and made real connections instead of going through a broker. We didn’t cut corners. Another reason is our product is delicious and approachable. And finally, the last reason is kombucha in general, it’s the fastest growing sector of the non-alcoholic beverage industry, so we’ve been very fortunate that we’ve gotten to ride that wave a little bit. We don’t have a lot of natural competition where we are. Kombucha is still a lot of west coast companies, and shipping is really expensive across the country. So we’ve been able to compete very directly in terms of price point with these multi-million dollar companies that are backed by Coca Cola and Pepsi.

Q: That’s impressive you can compete with the big brands.

Bufano: We started selling under the Wild Kombucha label in 2015. We were in Whole Foods in August 2016.

Malarin: We were selling at the side of a juice shop, initially. We didn’t have any starting capital. We were a bunch of 24 year olds, so no bank wanted to give us loans. We found a way to get around a lot of the licensing from the health department. We went to an active juice shop that had all the licensing, and we were able to circumvent all those costs by operating through a sublease from them. We initially rented a space that was tiny.

Bufano: We were making enough kombucha that we couldn’t fit it in the fridges we had, so we actually had to sell them when they finished fermenting, on the same day, since it needs to be refrigerated. So when the fermentation day was done, we’d immediately have to put the kombucha in our cars and drive it around to stores.

Q: Most new food brands I talk to have to start at a farmer’s market to get their name out there. You guys were able to get Wild Kombucha into local stores very quickly.

Bufano: We didn’t really go the farmers market route. We area in some now, but it’s really been in the last year that we started doing the farmers market thing because we felt like we weren’t connected as much as we liked to be to the community, we felt we took a step back in the wrong direction after a certain point. that’s why we started the farmers market program so we could be back in it.

Q: Your production and offices are on the same site; you’re not using a copacker. Why was that important to you, to have everything on site?

Bufano: Company culture to us is really important. Creating a team of people that all have a common goal that we’re all working towards, you really feel more unstoppable in that sense. If you separate people – we noticed this with some of our offsite sales people that were in Philly – we felt disconnected. We always had trouble making them feel like they were a part of the team. We wanted to make them feel a part of the team as much as possible. We want to keep everyone as close as possible. A lot of our demo team actually works out of our facility and we pay for them to travel farther away to do demos and come back to the Baltimore office.

Malarin: With the copacking, or lack thereof, we produce everything in house. It’s been really important because, initially for us, it was very important to have full control of the product. Learning how to scale up and how to control it. At the end of the day, if you’re not making your own product, you’re just the middle man. We saw that go into effect in very negative ways for people that we’re friends with, people at other local companies. Once the copacker realized they were doing well, they’d raise their prices.

Bufano: Just relying on someone like that for your whole company and your whole product, that’s too big of a risk for us. Quality control is super important to us. We are right there all the time, making sure everything is how we like it.

Q: That enables you to be out on the production floor, too, monitoring brewing.

Bufano: Oh yes, I am right there. Watching the mother kombucha, singing to the cultures.

Q: How did you get funding to start Wild Kombucha?

Bufano: It was about $5,000 a person that we just put in.

Malarin: Shortly after, we signed a lease for a new space, but we did not have the money for it. We needed like $30,000 in the beginning. So we entered a business competition and the top prize was $30,000. So we signed the lease, then we went to the business competition and we won. It was called the Shore Hatchery at the Salisbury University Perdue School of Business, it’s a one-minute timed pitch, “Shark Tank” style. But they don’t take any equity, they just give you money, a grant. The most you can get it $45,000, but the most you can get at one time is $30,000. So we came and got the other $15,000 during the next competition.

Bufano: If that didn’t happen, we would have had to pull out of that lease. We would been a very different company.

Q: What would be your advice to other entrepreneurs wanting to start a fermentation brand.

Malarin: Don’t do it alone.

Bufano: I’d agree. Having the three of us was so amazing. If one of us was having a tough time, we could lean on the other person. You really feel lonely if you do something alone especially up to this caliber, you sacrifice your social life. Have a partner, give them some equity, do it together.

Q: Where do you see the future of the fermentation industry?

Malarin: It’s only going up. Soda sales have been tanking for a better part of the decade, if not longer, and there’s a lot of things coming in to fill the void. This whole expo is a testament to that.

Bufano: The awareness for kombucha seems to be growing faster than the industry is growing, the market share doesn’t seem to be getting smaller even with more companies popping up. More people are getting educated about kombucha.

Malarin: A lot of the other kombucha companies on the market help us, if they’re doing it the right way. Because they educate people on it, then those people, when they come into our area, they’re much more likely to try our product.

Bufano: It’s between 5 and 10 percent of the U.S. population that doesn’t know what kombucha is.

Sergio: Very few people know about it still, so there’s a lot of room for growth.

Q: What challenges do you think fermented drink producers and kombucha producers face?

Bufano: It might not be as big as an issue anymore, but just educating the government agencies about what kombucha is, that’s been a huge hurdle for us. Especially in smaller cities if you’re the first fermented beverage company that opens there. Educating them about it, especially the health department, that was huge for us. You have to create a whole other category for yourself.

Malarin: It will be nice too when there’s more regulation on labeling kombucha. Right now, people throw kombucha on whatever they want and it’s not kombucha at all. Its misleading and it’s confusing to people.

Bufano: We look forward to the day that kombucha is labeled correctly, so you can see what is authentic kombucha and what isn’t.

Q: What strengths do you think kombucha producers bring to the industry?

Malarin: I feel like a lot of kombucha producers in one way or another are very tied to the communities they produce in. Much more than these huge conglomerates, so I think it brings this much more dynamic side to business that a lot of these huge corporations just can’t have. It’s changing the whole way business is done, reverting to something a little more personal.

Bufano: What I’ve seen from other kombucha companies, they treat their employees really well, at least what we’ve seen so far. I think that’s kind of been a norm in the industry, which is pretty cool.

- Published in Business

From Brewing in Apartment to Top U.S. Kombucha Brand: Health-Ade Kombucha

LA Times shares the story behind Health-Ade Kombucha, one of America’s top kombucha brands that will sell more than 4 million cases this year. It’s hard to believe the mega kombucha label began at a farmers market in 2012, with labels attached to bottles with scotch tape. Health-Ade struggled at the start, getting evicted from their apartment for brewing kombucha and racking up parking tickets when they drove kombucha around for distribution in their own cars. CEO Daina Trout said the company’s founders “were ‘success at any cost’ types of people.”

Read more (Los Angeles Times)

- Published in Business

Alcohol Policy Expert: Lawmakers Must Stop Antiquated Tax Laws on Kombucha Producers

An alcohol policy expert calls for an end to antiquated alcohol excise tax laws, which are unfairly penalizing kombucha producers across the country. Though kombucha only has trace amounts of alcohol (generally below the 0.5% alcoholic beverage threshold), it is “nearly impossible for kombucha producers to control the entire supply chain,” writes Jarrett Dieterle, Director of Commercial Freedom for R Street Institute and the author of forthcoming book “Drink For Your Country.” If not properly refrigerated once it’s left the manufacturer for distribution, kombucha will continue to ferment and raise the alcohol level. Dieterle said it’s unfair to make kombucha makers pay fines of more than $10,000 when they can’t control how the drink is stored once it enters the supply chain. Protecting kombucha, he says, should be a priority for federal lawmakers.

Read more (Washington Examiner)

- Published in Business