Bottoms Up! Scientists Find Gut-Friendly Bacteria in Unpasteurized Beer

The same beneficial gut-friendly bacteria prevalent in yogurt is also in some beer, according to new research from scientists at Amsterdam University. Beer brands that ferment twice — once at the brewery, then a second fermentation in the beer bottle — are rich in probiotic yeast. This creates a sharp, dry taste in the beer that is “bursting with probiotic microbes.” Scientists found the brands using in-bottle fermentation use a different strain of yeast than traditional brewer’s yeast. Pasteurized beer and modern beer production processes have no probiotics. Their findings are supported by researchers from the University of Nebraska, who also found some beers contain a high amount of good probiotics. Professor Eric Classeen, a gut bacteria expert from Amsterdam University, said “You are getting a stronger beer that is very, very healthy. … In high concentrations, alcohol is bad for the gut but if you drink just one of these beers every day it would be very good for you.”

Read more (The Telegraph)

- Published in Science

Do Clickbait Headlines Distort Fermentation Science?

By: Dr. Miin Chan, BMedSci, MBBS (University of Melbourne)

Good gut health fixes everything! Fermented foods are good for your gut! Fermented foods are a panacea for all that ails you!

As two behemoth trends in science and food – the gut microbiome and fermented foods – collide, messages such as these inundate the public narrative. But do they serve to educate, or confuse?

Everyone has their pet peeve. Mine is the violation of science to sell products and agendas. Intentional or otherwise, poor science communication distorts food literacy. Nutritional research is vulnerable to extreme manipulation, plagued by methodology issues, historical reputation damage and abuse by powerful commercial interests. In this era of rapid dissemination of alternative facts, it is essential to interpret and communicate research in a clear, accurate manner. These narratives guide our community’s daily food choices and thus, impact personal and public health outcomes.

Nuance and doubt are the key drivers of scientific practice; clickbait headlines and definitive language are the bread and butter of modern journalism and advertising. Private enterprise is the worst offender, exaggerating the health benefits of food products with purposeful vagaries and definitive language. Correlation and association in trials become causation. Studies in rodents equate to human health outcomes. The word “may” makes it acceptable to overstate findings or attribute them to unrelated food products. Labels and catchphrases are used loosely; think “probiotics”, “prebiotics” and the very grey “good for your gut health”. As a marketing strategy, many businesses now employ teams of “experts” to validate their claims’ scientific rigour, obscuring the inherent conflict of interest. These tactics serve to plump bottom lines, dodge government regulations that serve public interest, and ultimately, confuse vulnerable consumers.

Just as concerning are journalists, researchers and scientific publications that, in an effort to stay relevant, adopt the same techniques as their commercial counterparts to garner attention. Usually, this entails overblown health benefits. But sometimes it goes the other way.

Let’s look at a recent article published by The Conversation titled: “Kombucha, kimchi and yogurt: how fermented foods could be harmful to your health” (1). By the time it had been republished in The Independent, as well as several other international news outlets, it had morphed into: “Why fermented foods could cause serious harm to your health”. Such headlines instill fear in readers. Headlines are important: research has shown that 59% of links shared on social networks are not clicked on (2); this means that the majority of people share articles without reading past the headlines. These insidious messages bleed into the collective consciousness and impact our attitudes towards food.

Overall, this is a well-written article, providing mostly appropriate references, but the author is an infectious disease expert, not a food scientist or nutrition researcher. To the average lay reader, her non-related credentials give the article clout and credibility. Lurking within the article are problematic false equivalences, misrepresentations and extrapolations used to bulk out the piece.

Bloating is an issue for some consumers but is certainly not “harmful” nor “serious”. Reactions to biogenic amines, including histamine, are highlighted. But the article fails to mention that only 1% of the population (3) have histamine intolerance and even fewer have severe reactions. Why include food borne illness? This is a food safety issue and is not more likely to occur in fermented foods. The author even talks about how probiotics in milk products increase their safety, but then states that “probiotics can fail” leading to “hazardous” outcomes due to bacterial toxins, with no evidence to support this.

Lab-produced probiotic strains are not necessarily the same as those found in fermented foods (4). So it is misleading, in this context, to reference limited case reports of probiotic capsules causing infections in immunocompromised patients. There are no recorded infections due to the ingestion of fermented products, and the majority of people are not immunocompromised.

Last but not least, the author cites antibiotic resistance due to gene transfer from microbes found in fermented foods. The research used to support this looks at particular strains extracted from fermented foods in non-human trials. No evidence is currently available to suggest that such gene transfer occurs when humans ingest fermented food, or that this would promote antibiotic resistance in a clinically significant way. It is irresponsible to include this as a reason why fermented foods may cause harm to human health.

Humans have consumed fermented foods for many human generations. This in itself suggests the safety of fermented foods for the majority of people, and the human clinical trials that have been conducted indicate few side effects, let alone serious ones.

Fear-mongering headlines and articles exploit poor science literacy in the general population. One has to ask, what is the purpose of such articles? Is it simply a matter of publish or perish, a hankering for a sparkly headline that draws attention?

Food is central to every human’s daily life, with long-term effects on their health and wellbeing. Businesses, journalists, government bodies and most of all, scientists, need to recognise their responsibility to create clear nutritional science narratives. Science and food literacy need to be priorities in our education sector. Government bodies, informed by up-to-date research, must better regulate food-related health claims to protect public interest. We must avoid exaggeration of both benefits and harms and introduce nuance into our science communication. Our health depends on it!

Dr. Miin Chan, BMedSci, MBBS (University of Melbourne) As a medical doctor & researcher obsessed with taste, food culture, ferments and nutrition, Miin founded Australia’s first tibicos business, Dr. Chan’s. She helped to create the local wild fermentation industry through products, education, science communication and consultation. Working with farmers’ markets, Slow Food Melbourne and urban agriculture charity Sustain, she has a deep love for all things food, from soil to gut. Engaged in a love affair with microbes, Miin is undertaking a PhD at the University of Melbourne researching the effects of fermented foods on chronic disease via gut microbiota. @dr.chans @slowferment @gastronomymagic

(1) Mohammed, M. Kombucha, kimchi and yogurt: how fermented foods could be harmful to your health. The Conversation 2019. https://theconversation.com/kombucha-kimchi-and-yogurt-how-fermented-foods-could-be-harmful-to-your-health-126131

(2) Gabielkov M, Ramachandran A, Chaintreau A, et al. Social clicks: what and who gets read on Twitter? ACM SIGMETRICS/ IFIP Performance 2016. Antibes Juan-les-Pins, France (Conference Paper) https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01281190

(3) Maintz L, Novak N. Histamine and histamine intolerance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007; 85(5):1185-1196 https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1185

(4) Marco ML, Heeney D, Binda S, et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2017;44:94-102 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27998788

How Alcoholic is Kombucha?

Researchers are studying kombucha to determine whether kombucha brands are unintentionally selling the fermented tea with a high alcohol content. The study, by the British Columbia Center for Disease Control, is testing hundreds of kombucha samples sold at grocery stores and farmers markets for ethanol levels. The fermentation process makes all alcohol slightly alcoholic, but in the U.S. the drink has to be sold below 0.5% to be sold as a non-alcoholic beverage. In Canada the amount is higher, at 1.1%. Researchers are looking at how different control factors affect kombucha’s alcohol content, like how cold refrigeration temperature, where it’s stored in the fridge, how it’s made and type of tea and flavors used.

Read more (CTV News)

- Published in Science

Grant Funds Educational Materials, Research on Fermented Foods

A new grant by the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) to the University of California at Davis will fund training and education for consumers around one of the most confusing grocery offerings — fermented fruits and vegetables.

“There’s a general need to educate the consumer on what fermented foods are — and they currently don’t have that education,” says Maria Marco, professor in Food Science and Technology at UC Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board member). “A definition and resources will help them be more empowered consumers and be more aware of what they’re eating. There’s a need — from kids to physicians. People need to know what these foods are.”

The grant will also fund research on the fundamental properties of fermented fruits and vegetables. Food scientists at UC Davis will study the microbial contents, characterizing the fermented foods.

The 2019 Specialty Crop Block Grant Program (SCBGP) funds 69 projects focusing on specialty crops grown in California. Grant recipients range from organizations, government entities and colleges and universities. The projects must specifically focus on increasing the sales of specialty crops through the “California Grown” identity. UC Davis received $213,051 for the grant titled: “Expanding Education and Knowledge of Fermented Fruits and Vegetables.”

“California has an important role in the U.S. because such a large number of the United States’ crops are grown here,” Marco said. “We’re the fruit bowl, the salad bowl here in the U.S.”

Of the $72.4 million awarded nationwide, California led the nation in funding with $22.9 million. The California Department of Agriculture will oversee the projects.

Fermentation Education

Core to the grant is fermentation education. UC Davis will work with Master Food Preservers across the state, training them in fermentation. The Master Food Preserver is a community volunteer program available to any individual interested in food preservation. They take a series of extensive, in-depth courses. After earning certification, they can teach the public about food preservation.

“These Master Food Preservers are getting a lot of questions lately about making fermented foods at home,” adds Marco. By providing fermentation classes to the Master Food Preservers, “we’re extending knowledge and providing information on the science of fermented foods.”

“When people start to understand the science behind the food, what the microbes are doing, that engages the public in a way based on science rather than on feeling. That will help the food producers in the end. A more informed public helps elevate their product. It shows their product is different from something just pickled with acid.

Citizen Science

Education and training will be supported by up-to-date research. This research, performed in UC Davis’ Marco lab in the Food Science & Technology department, will also be funded by SCBGP money.

“We’ll be looking at microbial contents of crops and the metabolites that they make,” Marco added. “Characterizing those foods to provide more knowledge on what’s there, it’s a move forward to determining how fermented foods can be healthy for us.”

Few studies are available that examine how fermented foods benefit or alter human health. Though fermented food research in the Marco Lab won’t involve humans, it will provide a scientific base that could evolve into a human study.

“This is important because there’s a lot of interest in this type of food and beverage. You see a lot more of these products available on the supermarket shelves. There is also an interest to be making more food at home. And there’s generally an idea that these foods are first of all tasty, but they could help our health in many, many ways. There is that belief. And there’s a risk — if these things are not made properly or if there’s some conditions where people should limit their fermented food intake. So there’s good, but if these things are not made properly there can be food safety risks.”

Food Processors

Grant research will benefit commercial processors, too. UC Davis will provide “new or improved methods for fermented food processors.”

Consistency and scale are a challenge for fermented food producers because of the live bacteria.

“Microbes have a mind of their own,” Marco said. “A lot of these foods are not originated with mass production in mind. They are usually made in small quantities. So when you scale up, it becomes an issue of quality and consistency. How do you make something that’s usually done in small quantities and sell across the country in large quantities?”

- Published in Science

Taming the Wild Cheese Fungus

By: The American Society for Microbiology

The flavors of fermented foods are heavily shaped by the fungi that grow on them, but the evolutionary origins of those fungi aren’t well understood. Experimental findings published this week in mBio offer microbiologists a new view on how those molds evolve from wild strains into the domesticated ones used in food production.

In the paper, microbiologists report that wild-type Penicillium molds can evolve quickly so that after a matter of weeks these strains closely resembled their domesticated cousin, Penicillium camemberti, the mold that gives camembert cheese its distinctive flavor. The study shows how a fungus can remodel its metabolism over a short amount of time; it also demonstrates a strategy for probing the evolution of other cultures used in food, said study leader and microbiologist Dr. Benjamin Wolfe, Ph.D., a member of the The Fermentation Association advisory board.

“In fermented foods, there’s a lot of potential for microbes to evolve and change over time,” said Wolfe.

Wolfe’s lab at Tufts University in Medford, Mass., focuses on microbial diversity in fermented foods, but he says the new experiments began with an accidental discovery. His lab had been growing and studying Penicillium commune, a bluish, wild-type fungus well-known for spoiling cheese and other foods. Wolfe likens its smell to a damp basement.

But over time, researchers noticed changes in some of the lab dishes containing the stinky mold. “Over a very short time, that funky, blue, musty-smelling fungus stopped making toxins,” Wolfe said. The cultures lost their bluish hue and turned white; they smelled like fresh grass and began to look more P. camemberti. “That suggested it could really change quickly in some environments,” he said.

To study that evolution in real-time, Wolfe and his collaborators collected fungal samples from a cheese cave in Vermont that had been colonized by wild strains of Penicillium molds. The researchers grew the molds in lab dishes containing cheese curds. In some dishes, the wild mold was grown alone; in others, it was grown alongside microbes that are known competitors in the fierce world of cheese colonization.

After one week, Wolfe said, the molds appeared blue-green and fuzzy—virtually unchanged—in all the experimental tests. But over time, in the dishes where the mold grew alone, its appearance changed. Within three or four weeks of serial passage, during which mold populations were transferred to new dishes containing cheese curds, 30-40 percent of the mold samples began to look more like P. camemberti. In some dishes, it grew whiter and smoother; in others, less fuzzy. (In the competitive test cases, the wild mold did not evolve as quickly or noticeably.)

In follow-up analyses, Wolfe and his team tried to identify genomic mutations that might explain the quick evolution but didn’t find any obvious culprits. “It’s not necessarily just genetic,” Wolfe said. “There’s something about growing in this cheese environment that likely flips an epigenetic switch. We don’t know what triggers it, and we don’t know how stable it is.”

Researchers suspect that the microbes used in most fermented foods—including cheese, but also beer, wine, sake, and others—were unintentionally domesticated, and that they evolved different flavors and textures in reaction to growing in a food environment. Wolfe says his lab’s study suggests that wild strains could be domesticated intentionally to produce new kinds of artisanal foods.

Starting with cheese, of course. “The fungi that are used to make American camembert are French,” said Wolfe, “but maybe we can go out and find wild strains, bring them into the lab, and domesticate them. We could have a diverse new approach to making cheese in the United States.”

###

The American Society for Microbiology is the largest single life science society, composed of more than 30,000 scientists and health professionals. ASM’s mission is to promote and advance the microbial sciences.

ASM advances the microbial sciences through conferences, publications, certifications and educational opportunities. It enhances laboratory capacity around the globe through training and resources. It provides a network for scientists in academia, industry and clinical settings. Additionally, ASM promotes a deeper understanding of the microbial sciences to diverse audiences.

- Published in Science

Break Out the Kimchi: Study Finds Spicy Kimchi Cures Baldness

Spicy kimchi cures baldness and thickens hair, according to a new scientific report published in the World Journal of Men’s Health. Researchers from Dakook University in South Korea studied men in early stages of hair loss who consumed a kimchi probiotic drink twice a day. After a month, hair count increased from 85 per square centimeter to 90; after four months, hair count increased to 92. Results were even faster and prevalent for female patients with hair loss, who went from an average of 85 hairs per square centimeter to 92 after one month. Hair thickness also increased. This is exciting research for people suffering from hair loss; the kimchi and probiotic product is a natural, safer alternative to hair regrowth drugs. Current hair regrowth drugs have adverse side effects, like irregular heartbeat, weight gain and diarrhea.

Read more (World Journal of Men’s Health)

- Published in Science

Gut Health Hot Food Trend, But Consumers Confused Over Science and Additives

As more people battle digestive problems, they’re turning to brands offering gut health solutions. Digestive health is the third most sought after health benefit in the latest International Food Information Council Food & Health Survey, behind weight loss and energy.

Though it’s a hot topic, it’s a space challenged with unsupported health claims and confusing ingredient additives. During a panel hosted by Food Navigator, four industry leaders shared insight into the growing gut health category.

“What we’ve learned is that many of our consumers come into our brand typically with serious, long term digestive health challenges. Bloating, regularity challenges, IBS,” said Mitchell Kruesi, senior brand manager for Goodbelly, which creates probiotic drinks and snacks. “They’ve tried supplements in the past, but weren’t super enthusiastic about them because often times taking a supplement felt medicinal to them. After that, they continue to seek out other probiotic options that are both effective, but also food-based so that it’s easy to fit in their routine.”

Demystifying Probiotics

Plagued with health issues and fed-up with pills, consumers are desiring food brands that aid digestive health. Flavor, though, is key.

“That delicious taste…it sets up an everyday usage routine, which is critical with probiotics,” Kruesi said.

Probiotics is a confusing territory for consumers. Should probiotics be consumed in pills or as a strain added to food? How much should be taken?

Elaine Watson, Food Navigator editor, quoted GT Dave, founder of GT Kombucha: “In my mind, anything raw and fermented deserves to use the term ‘probiotic.” Watson asked the panelists if there’s a perception that all fermented foods contain probiotics because they contain live, active cultures – and should food advertising probiotics be verified by clinically proven studies?

“I think consumers are quite confused still around the whole topic, in all honestly. Live, active cultures are used to make fermented food beverages – but unlink probiotics, they’re typically not studied and shown to provide a health benefit,” said Angela Grist, Activia US marketing director. Really in order to be considered a probiotic, they would need to meet the criteria of survival and research-validated health benefits and also this point around strain specificity.”

Grist said probiotics need to survive the passage through the digestive track to the colon. Activia has five survival studies showing the benefits of probiotics.

Ben Goodwin, co-founder of Olipop, added he’s conducted genetic assays around the underlying culture banks of fermented food and beverages and “there have definitely been organisms in the culture banks which are deleterious for human health. So not everything that’s fermented is automatically good for human health, there’s all sorts of different biological modes that organisms can interact with each other and some become parasitic or become determinantal to your probiotic when consumed, so something to keep in mind.”

Note that the panel did not feature a raw, fermented food brand; the companies included on the panel all add probiotic strains to their food and drink product.

In a separate interview with The Fermentation Association, Maria Marco, professor in the Department of Food Science and Technology at the University of California, Davis, said there is a lot of confusion around probiotics, even among industry representatives. Marco, though, agrees with Grist and Goodwin. She says clinical studies on fermented foods are necessary.

“Although it might be possible to separate out the individual components of foods for known health benefits (e.g. vitamin C), the benefits of many foods are likely the result of multiple components that are not easily separated,” Marco said. “Yogurt consumption is a great example of a fermented food that, through longitudinal studies, was shown to be inversely associated with CVD risk.”

In one of Marco’s studies at UC Davis titled “Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond,” Marco and her research associates concluded that fermented foods: are “phylogenetically related to probiotic strains,” “an important dietary source of live microorganisms,” and the microbes in fermented foods “may contribute to human health in a manner similar to probiotics.” The study adds: “Although only a limited number of clinical studies on fermented foods have been performed, there is evidence that these foods provide health benefits well-beyond the starting food materials.”

Educating Consumers

The panel said that the food industry is responsible for displaying integrity in their marketing on probiotic benefits.

“We believe it’s critical for leading brands in the space…to really educate consumers on, first, what probiotics are,” said Kruesi with Goodbelly. Consumers are seeking out probiotics for a specific health benefit, but most don’t know what strain they need to address their issue, he noted.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that aid the digestive system by balancing gut bacteria.

Currently, the demographic of consumers buying products geared toward gut health are millennial females in coastal cities. Both Activia and Olipop sell to more women than men (Activia customers are 60 percent female and 40 percent male; Olipop customers are 55 percent female and 45 percent male).

Goodwin said Olipop is hoping to tap into the rapidly declining soda market. Soda is a $65 billion industry, with 90 percent household penetration. But more consumers are turning to healthier options than unnatural, sugar-filled soda.

“We’ve tried to take on the extra responsibility as a brand of formulating something that’s spun forward, delicious and really approachable so that we can meet a real health need in a way that’s actually supported by research,” Goodwin said. “(Olipop) is not only low sugar, low calorie, it also has this digestive health function but obviously doesn’t taste like vinegar because it’s not a kombucha.”

Solving Digestive Stress

Products by Activia, Goodbelly, Olipop and Uplift Food (the fourth panel member) are “meant to be a mass solution for the lack of fiber prebiotics and nutritional diversity in the modern diet,” Goodwin said. Fiber contains prebiotics, which aid probiotics.

The USDA’s dietary guidelines recommend adult men require 34 grams of fiber, while adult women require 28 grams of fiber (depending on age). The reality, though, is that most Americans get about half the recommended fiber a day, only 15 grams. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 60-70 million Americans are affected by digestive diseases.

Compare that to the diet of hunter-gatherers, who eat about 100-150 grams of fiber each day and maintain incredibly healthy guts or microbiome. The microbiome is the community of commensal microorganisms in our intestines, fed by fiber, probiotics and prebiotics.

“As it stands now, basically we’re putting in a starvation system for a lot of the microorganisms currently in your gut,” Goodwin said. “The average industrialized consumer has about 50 percent less diversity and abundance of beneficial microorganisms than the hunger-gatherers alive on the planet tonight.”

Future of Gut Health Products

Grist with Activia said probiotics need to be consumed in adequate, regular amounts to provide health benefits, or else probiotics will not consume the digestive track.

Kara Landau, dietitian and founder for Uplift Foods which makes prebiotic foods, added that each individual has a unique bacterial make-up, and providing diverse food to support the microbiome is critical.

Landau said the future of gut health probiotics will be selling a specific probiotic strain, one that a consumer can target for their desired health benefit. Prebiotics – “the fuel for the probiotics” – are also key, and a new part of the digestive health puzzle that brands need to communicate and simplify for consumers.

“Prebiotics are still very much in their infancy when it comes to consumer understanding,” Landau said. “Seeing them alongside probiotics enhances the clarity of their benefits.”

- Published in Science

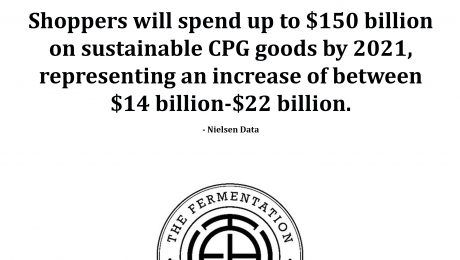

Sustainability Sells, Shoppers will Spend $150 Billion on Sustainable Goods by 2021

Sustainability sells. Shoppers will spend up to $150 billion on sustainable CPG goods by 2021, representing an increase of between $14 billion-$22 billion. – Nielsen Data

- Published in Business

Tim Spector: Stop Dieting, Start Diversifying What You Eat

Restrictive diets aren’t the secret to staying slim. The key is diversity says Tim Spector, professor and author of the book “The Diet Myth.” Eating foods high in fiber, fermented products and food loaded with micronutrient polyphenols are scientifically proven to improve weight and help the complex microbiome flourish.

“This is where we’ve lost track, we’ve tried to simplify it and we’ve tried to say that calories in equals calories out and that one-size-fits-all and that if everyone has these 2,000 calories a day, they’ll be perfect. And of course, that advice has led to the whole world getting fatter,” Spector says in an interview on webisode Health Hackers. “[People have been taught] erroneous advice that fat is bad for you therefore avoid all things with fat, even healthy things.”

The Health Hackers episode is titled “Why your diet may never work until you get to know your microbiome.” Journalist Gemma Evans interviews Spector in his London research lab. Spector is a professor of genetics at King’s College in London. He has published over 800 research articles, and Reuters ranked him as the top 1% of the worlds must published scientists.

Spector began researching the microbiome seven years ago, when he became sick and wanted to know which diet would help him heal. His early delve into the microbiome fascinated him.

“We hadn’t understood the gut microbiome, which is this whole new organ in our bodies that was previously ignored,” Spector says. “I really got into this whole field and diverted my group’s research interest into discovering more about that microbiome that we all have. We’re all so different in our microbes, and this difference is how we all respond differently to foods and it explains a lot of mysteries.”

Microbiome is a Living Community

Spector describes the microbiome as a living community of trillions of microbes that produce chemicals, vitamins and hormones. Ninety-nine percent of microbes are in the gut, most in the lower gut or colon. Human cells only make up 43% of the human body — the rest are microbe cells.

Healthy microbiomes are full of diverse species. They help avoid overeating or under eating because a healthy microbiome self regulates.

“The healthier your microbiome, the healthier your body is in general because it means that your immune system is being well balanced and not overresponding,” he says. “It’s giving you resistance against its infections; it’s not overreacting to give you allergies.”

Researchers like Spector study the microbes with fecal samples. He says you can tell more about a person and what they’re eating through their fecal matter. Many commercial companies today advertise accurate health measurements by measuring genes through DNA samples.

“As a geneticist, that’s rubbish,” Spector says. “Statistically, it might be true, but actually at a personally level, it’s virtually no use. Our microbes are so much different than our DNA makeup. We share any, for example, 20 to 30 percent of our microbes [between] any two people. And so, understand how that community is and what’s different should mean that I can tell whether someone is healthy or whether they’re more likely to get fat or diabetes, [by] looking at the general diversity [of their microbes]. And I can also try and now use this information when you’ve got thousands of people to predict what the best foods are for people.”

Healthy Eating Myth Busting

It’s fascinating insight into the future of predictive health. Spector’s book, “The Diet Myth,” detailed how the health industry has failed the general public for roughly the past 30 years. People were told to eat low-fat foods, count their calories and get lots of exercise. Spector calls that advice “very old-fashioned, very 20th Century.”

“We only really understood food around those primitive concepts in these very broad categories of fats and sugars and proteins and we’ve ignored one of the big ones, which is fiber,” Spector says.

Diets cannot revolve around the three blocks of fats, sugar and protein. What matters, Spector says, is the total amount of chemicals consumed and the effects on the body. Take, for example, a banana. A banana can’t be defined in one of the three categories because it’s made up of 600 chemicals. Once a banana is ingested and combines with gut microbes it converts to 6,000 chemicals.

Making the microbiome more complex: everyone will react differently to that same banana. The effects of the chemicals produced will present differently in each individual.

Diversifying Diets — and Microbes

“Virtually all diets, people end up restricting what they eat which actually has a long-term effect of reducing your microbes and therefore they’re less able to cope with modern living,” he adds.

Spector said you cannot generalize healthy eating guidelines with broad generalizations when it comes to the microbiome because everyone will react differently. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome.

“But if you had to have one rule, people on very restrictive diets don’t do well and people who have the more diverse diets…are healthier,” he says. This is because a diverse diet is full of different nutrients and, in turn, build a diverse group of microbes. Spector compares the microbiome to a garden – the nutrients consumed are like the fertilizer helping the plants or microbes grow.

As the head of the Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College, Spector has studied the effect of microbes in twins. In one study, two mice with different weights were analyzed. The overweight mouse with less diverse microbes was given a fecal transplant from his twin, the skinnier mouse with a healthier microbiome. Once that healthier mouse was given the fecal transplant, the overweight mouse continued to lose weight, even when overfed.

“So those microbes are doing a really good job working overtime to convert metabolically to keep that stuff away from going into fat. They’re burning it up in ways we don’t really understand,” Spector says. “Your chances of having good microbes will increase the more you’ve got of them. So the people who have very limited number of microbes, who have very limited diets where they’re just on processed foods, have an increasingly smaller amount of nutrients in there and only a few microbe species like that restrictive species and they elbow the others out and then they can’t react in healthy ways:

Society has to stop demonizing junk food, Spector says, “we have to get away from the idea that these things are so deadly.” Eating a fast-food burger once a year could actually be good for the microbiome, Spector argues, because it will “wake up your system.”

Another study on mice found that mice who consumed lots of fiber (chickpeas, lentils), then were given a high-fat meal didn’t put on weight. Spector said it’s because they had a solid base, and then were given a high-fat meal once in moderation.

Spector is against the concept of clean eating (“There’s no such thing.”) and even processed food (“What’s processed food? It’s cheese. It’s milk. It depends where you draw the line.”). But he says ultra-processed food with harsh chemicals should be kept to an absolute minimum. Ultimately, no one should take a black and white view on food and limit what they eat.

What Should We Eat?

So what should we eat? Spector highlighted four food and drinks that help gut health: foods high in fiber, complex plants, fermented foods and polyphenols.

Fiber is important because it’s what microbes live off. Fiber is hard to digest early in the digestive track, so the nutrients reach the colon before being absorbed. Most ultra-processed foods are so full of sugar that they are absorbed extremely early in the digestive process. Microbes are destroyed by starving them of fiber — microbes can be wiped out if not fed fiber for long periods of time.

Complex plants, Spector advises, prioritizing vegetables first and fruit second. Fermented foods are full of the live bacteria critical for gut health. Spector suggests fermented foods like kefir, yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha, Japanese fermented soy and even quality fermented chocolate. Polyphenols are an energy source for microbes, and can be found in any food like blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, olive oil, dark chocolate, seeds, coffee and green tea.

As far as pill supplements, Spector points out that there’s no scientific evidence yet that probiotic supplements benefit healthy people.

“I’m generally in favor of using food – yogurt, kefir, cheese — rather than expensive supplements,” he says.

- Published in Science

Fermenting Techniques of Three Northern California Sauerkraut Makers Highlighted

Who is enjoying some sauerkraut at their July 4th BBQs? Pacific Sun magazine featured three Northern California sauerkraut makers — Sonoma Brinery, Wildbrine and Wild West Ferments. The article highlights the different fermenting techniques of the three brands and features this fascinating insight from David Ehreth, president and managing partner at Sonoma Brinery:

“If I can go nerd on you for a moment,” Ehreth warns, before diving into a synopsis about the lactobacillus bacteria that exist on the surface of all fresh vegetables. “You can’t remove them by washing.” What’s more, they immediately begin to feed and reproduce — but not in a bad way, unless they’re a bad actor, he insists.

“Those bacteria will really stake out their turf,” says Ehreth. “They’re very territorial. They go to war with each other.” The incredible part of it is that the four horsemen of the food industry — listeria, E. Coli, botulinum, and salmonella—are on lactobacilli’s hit list. None survive. Five bacteria enter — one bacterium leaves.

Quoting the Food and Drug Administration, Ehreth states, “There has been no documented transmission of pathogens by fermented vegetables.”

Read more (Pacific Sun)

- Published in Science