Why are Sauerkraut and Kimchi Sales Up During the Pandemic?

People are turning to acidic dishes like sauerkraut and kimchi to protect themselves from the COVID-19 virus. Though there is no scientific evidence that foods like kimchi and sauerkraut will prevent spread of the virus, sales are booming. Health experts say it’s because cabbage is a superfood filled with antioxidants and vitamin C, and the fermented condiments are filled with probiotics that support the gut microbiome. Consumers are hypothesizing that coronavirus death rates in Germany and South Korea because sauerkraut and kimchi are traditional food staples in the two countries. In January, South Korea’s national health ministry issued a press release stressing that kimchi offers no protection against the virus. That hasn’t stopped Americans from buying it – sauerkraut sales surged 960% in March, while kimchi sales jumped 952% in February.

Doctors emphasize that the best way to prevent coronavirus infection is to avoid becoming exposed. Hand washing, social distancing and mask wearing are encouraged.

Read more (New York Post)

Farmer, Nutrition Activist Uses Fermentation Methods to Create Healthier School Lunches

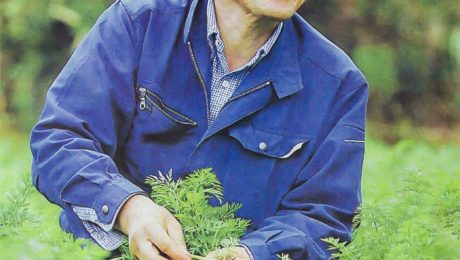

An organic farmer and nutrition activist is teaching schools and daycare centers in Japan to grow their own vegetable garden using fermented compost from recycled food waste, then incorporate into school lunches those fresh vegetables with traditional Japanese fermented foods (like miso and pickles). Two years after the program’s launch, absences due to illness have dropped from an average of 5.4 days to 0.6 days per year.

Farmer Yoshida Toshimichi “is a devout believer in the power of microbes.” Using centuries of Japanese folks wisdom that is supported by modern science, Toshimichi explains that fermentation bacteria in the compost yields hardy, insect-resistance vegetables. He says the key to a healthy immune system is maintaining a diverse and balanced gut microbiota. “Lactobacilli and other friendly microbes found in naturally fermented foods can help maintain a healthy environment in the gut, just as they do in the soil,” continues the article. Microorganisms in fermented foods like miso and soy sauce will help balance gut flora. “Organic vegetables, meanwhile, provide the micronutrients and fiber on which those friendly bacteria thrive. In addition, phytochemicals found in vegetables—especially, fresh organic vegetables in season—are thought to guard against inflammation, which is associated with cancer and various chronic diseases,” the article reads.

Toshimichi has authored books on his farming and nutrition practices and is featured in the two-part documentary film “Itadakimasu,” which translates to “nourishment for the Japanese soul.”

Read more (Nippon)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

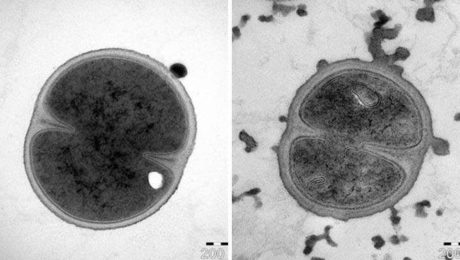

Peptide Found on Fermented Veggies Aids Antibiotics Research

Microbiologists in Sweden discovered a major breakthrough in antibiotics. Their research found an antibacterial peptide, plantarcin, can be combined with antibiotics to kill the staphylococcus bacteria (MRSA). Staph is a major problem in healthcare, which causes difficult wound infections and, in severe cases, sepsis. This plantarcin peptide comes from good bacteria — it’s found on fermented vegetables, which serve as a natural preservative for the food. The results of the study were published in the journal Scientific Reports. “Administering lower doses of antibiotics when treating infections in turn reduces the risk of further development of antibiotic resistance, which today is a major global threat to public health,” says Torbjörn Bengtsson, professor in medical cell biology at Örebro University.

Read more (Phys.org)

The Science of Yeast, the Microbe in your Pandemic Bread

Humans have been baking fermented breads for at least 10,000 years, but commercial yeast and flour companies have never seen demand so high. National Geographic shares “a story for quarantined times, about extremely tiny organisms that do some of their best work by burping into uncooked dough.”

Scientists describe the microbes behind the work fermenting the bread. “It’s this wonderful living thing you’re working with,” says Anne Madden, a North Carolina State University adjunct biologist who studies microbes. She and partner scientists showed recently that when bakers in different locales use exactly the same ingredients for both starter and bread, their loaves come out smelling and tasting different. “Which I think is fantastic,” she says. “It’s evidence of the unseen. And as a microbiologist, you so rarely get to measure things about microbes with your nose and your taste buds.”

Read more (National Geographic)

- Published in Science

Bubbling Over: How to Prevent Mold in Sauerkraut

Three fermentation experts weigh in on one of the most common problems in fermenting vegetables: mold prevention. The fermenters include fermentation chef David Zilber (head of fermentation at Noma) and fermented sauerkraut producers Meg Chamberlain (co-owner of Fermenti Farm) and Courtlandt Jennings, (founder and CEO of Pickled Planet and TFA advisory board member).

How do you handle prevent mold in sauerkraut?

David Zilber, Noma: That is something you are constantly trying to fight back, especially when you lacto-ferment in something like a crock. There are so many variables that go into making a successful ferment. How clean was your vessel before you put the food in there? How clean were your hands, your utensils? How much salt did you use? How old was the cabbage you were even trying to ferment in the first place? Every little detail is basically another variable in the equation that leads to a fermented product being amazing or terrible. It’s a little bit like chaos theory, it’s a little bit like a butterfly flapping its wings in Thailand and causing a tornado in Ohio. But with lots of practice, you’ll begin to understand that, if it was 30 degrees that day, maybe things were getting a little too active, maybe the fermentation was happening a little bit too quickly. Maybe I opened it a couple times more than I should of and it was open to the air instead of being covered. So there’s lots of variables. But I would say that, if you’re having a lot of trouble with mold, just up the salt percentage by a couple percent. It will make for a saltier sauerkraut, but it will actually help to keep those microbes at bay. (Science Friday)

Meg Chamberlain, Fermenti Farm: You must allow the ferment to thrive by creating a favorable environment with “Good Kitchen Practices.” So, to prevent mold in your ferment start by using only purified water, like reverse osmosis, distilled or boiled and cooled and-no tap water(municipal). Only use vegetable-based soap that is NOT anti-bacterial, like a good castile soap. Finally, only use dry fine Sea Salt, no mineral/no gourmet or iodized. Keep Fermenting and do not get discouraged! #youcanfermentthat #diyfermentation #idfermentthat

Courtlandt Jennings, Pickled Planet: Preventing mold when making sauerkraut is all about a controlled atmosphere. How well you maintain your situational cleanliness and fermenting atmosphere is my best clue for you. There are many ways to control atmosphere and every situation will be different based on many factors but be dillegent and your ferments will improve with practice.

This may not seem like an answer but it’s directional… as is most advice unless dealing with a consultant. Good luck and may the ferment force be with you!

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Sourdough Library Catalogues Hundreds of “Mothers”

The man behind the world’s only sourdough library shares how he maintains a collection of 125 sourdough mothers from all over the world. The mothers are stored in Mason jars in a chilled cabinet. Library founder Karl De Smedt cares for them in France, refreshing the jars every two months with back stocks of the original flours used (and contributed) by the providers. De Smedt travels the world for new mothers, prioritizing “renown, unusual origins, the type of flour used, and the starter’s approximate age.” He adds up to two dozen new sourdoughs each year, ranging from cooking schools, home-bakers, pizzerias, artisan and industrial bakers.

“Most importantly, the sourdough must come from a spontaneous fermentation, and not inoculated with a commercial starter culture,” De Smedt says. “Sourdough is the soul of many bakeries. When bakers entrust you with their souls, you’d better take care of it.”

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Science

What Gives Kimchi its Bacteria Superpower?

A fascinating study by the World Institute of Kimchi (WiKim) found that the cabbage in kimchi is a key source of lactobacilli in the fermented product. Garlic also contributes to the lactobacilli, while ginger and red pepper did not contribute. Of note, neither cabbage or garlic alone could replicate the final community of fermented kimchi. All vegetables were needed to bring the full bacterial community. The findings were published in the journal Food Chemistry. Researchers say it’s a building block to further understand food.

Peter Belenky, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology who analyzed the study, said: “I think really what it tells us is that, yes, some ingredients bring specific bacteria, but you really need everybody working together in order to bring the full community.”

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Science

Fermenting “Cowcohol”

Oregon-based TMK Creamery is using the leftover whey byproduct from their cheese and fermenting it into vodka. They call it “cowcohol” and the flavor has a carmel-like sweetness with a smooth finish. Owner Todd Koch learned about the method from Dr. Paul Hughes, assistant professor of Distilled Spirits at Oregon State University. Hughes began experimenting with fermenting whey into a spirits base and has now helped more than a dozen creameries all over the U.S. ferment their whey into alcohol.

Fermenting upcycles the whey while bringing some attention to the animals, Koch said. Artisanal creameries typically have to pay thousands of dollars to dispose of whey in landfills.

From Atlas Obscura: Whey fermentation offers a brave, new world for small creameries, both in decreasing their environmental footprint and ensuring financial security in an age of mass conglomeration. For Koch, a life-long, self-proclaimed “cow person,” the possibilities of bovine booze are a relief to him and his beloved herd. “Going through college, I was like ‘Man, if I could just figure out how to get cows to make alcohol, we’d be set,’” he says. “So I guess we’re one step closer here.”

Read more (Atlas Obscura)

How Fermented Food Affects Our Gut

Americans are hearing the term “microbiome” a lot lately. It’s become a common phrase in health food marketing. But the microbiome is still uncharted territory in science.

Dr. Shilpa Ravella, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center, says a large army of trillions of bacteria lives on or in us, and we can alter that bacteria by fueling it with the right (or wrong) foods.

“There are also ways of preparing food that can actually introduce good bacteria, also known as probiotics, into your gut. Fermented foods are teeming with helpful probiotic bacteria, like lactobacillus and bifidobacteria,” Ravella says.

Fermented food and drink are critical to caring for gut bacteria. Because fermented products are minimally processed and provide nutrient-rich variety to diets, she adds.

But that doesn’t mean all fermented products are created equally. Yogurt is a beneficial food, for example, but some brands add too much sugar and not enough beneficial bacteria that the yogurt may not actually help.

Ravella shared her insight in a TedED talk. As the director of Columbia’s Adult Small Bowel Program, she works with patients plagued by gut issues.

“We don’t yet have the blueprint for exactly which good bacteria a robust gut needs, but we do know it’s important for a healthy microbiome to have a variety of bacterial species,” she adds. “Maintaining a good balanced relationship with them is to our advantage.”

Gut bacteria breaks down food the body can’t digest, produces important nutrients, regulates the immune system and protects our bodies from harmful germs.

Though multiple factors affect our microbiome – the environment, medications and even whether or not we were birthed vaginally or through a C-section – the food we eat is one of the most powerful allies for the microbiome.

“Diet is emerging as one of the leading influences on the health of our guts,” Ravella adds. “While we can’t control all these factors, we can manipulate the balance of our microbes by paying attention to what we eat.”

In addition to fermented food and drink, fiber is also key. Dietary fiber in foods like fruit, vegetables, nuts, legumes and whole grain are scientifically proven to colonize the gut.

“While we’re only beginning to understand the vast wilderness inside our guts, we already have a glimpse of how crucial our microbiomes are for digestive health,” Ravella says. “We have the power to fire up the bacteria in our bellies.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Fermentation Grows Sustainable Alternative for Protein

The new wave of protein is not plant-based — it’s fermented.

“Fermentation is really cultivating microbes,” says Thomas Jonas, CEO and co-founder of Sustainable Bioproducts. “And it’s incredibly efficient. Microbes duplicate very fast. So when you think about the double time for a cow or a pig, you’re talking about years. When you talk about microbes, you’re talking about hours. … This is nature’s technology. Nature is really the No. 1 biotech engineer in the world.”

The current agriculture system is incredibly inefficient. Livestock continues to be the world’s largest user of land resources. Pasture land consumes 80% of total agricultural land. Fermented organisms are emerging as new sources of proteins and ingredients.

Leaders in the biotech industry shared how science is looking beyond plants to create food at a panel sponsored by The Good Food Institute.

Is Microbe Fermentation the New Era of Farming?

Sustainable Bioproducts creates a 50% protein based food ingredient from a microbe cultivated in the volcanic springs at Yellowstone National Park. Jonas explains that these fungal strains, called extremophiles, naturally produce a complete protein when grown in a controlled environment. Sustainable Bioproducts will soon move to a 36,000-square foot facility in Chicago’s former meatpacking district for production. The facility will take up just 0.7 acres. Compare the amount of food Sustainable Bioproducts produces to the equivalent of cow meat and 7,000 acres of grazing land would be needed for the cows.

“It’s the next generation of very efficient farming. I think what we want to get through farming are the nutrients that we need for our food. And microbes can do this tremendously efficiently,” Jonas said.

By fermenting proteins in bioreactors versus deriving the protein from plants or raising it and slaughtering it on a feedlot, food scientists can do a lot with the health profiles.

Michele Fite, chief commercial officer for Motif FoodWorks, said they work with microbes to adjust sensory attributes, like taste, smell, flavor and texture. “We can help so we don’t have to compromise taste or nutrition when consumers are looking to access plant based foods,” she said.

Adds Anja Schwenzfeier, business development manager for Novozymes: “You want to produce specific proteins that might already exist, but you want to do that more efficiently and more sustainably. You deal with molecules you’re already familiar with.”

“It’s not so much about creating a completely new protein. Right now we’re looking into how we can improve ingredients we already work with through fermentation.”

Fermentation as a Marketing Advantage

Panel moderator Jeff Bercovici, a writer for the Los Angeles Times, asked how biotech companies are meeting consumers in the development of fermented meat alternatives.

“(There is an) evolution of consumer attitude towards their food, which in some ways are really driving them very quickly to embrace meat alternatives, but in some ways there are some counter currents in terms of people wanting to eat whole foods, natural foods, foods with shorter ingredient lists,” Bercovici said.

The panel noted fermentation has long been a stable in the history of food, from beer to yogurt to cheese. As fermentation is making a comeback, it’s a “marketing advantage,” Bercovici notes, “now it’s a net positive, it generates consumer excitement.”

Fite at Motif FoodWorks said they’ve conducted research on meat alternative users. These consumers are currently buying meat alternatives because they believe it’s healthier than red meat and even chicken. “They want to be in this space,” she said. Consumers voice that meat alternatives are more sustainable, better for the environment, better for animal welfare and equally nutritious.

“They’re open to technology helping to solve that issue for them,” she said. “These consumers are more open to technical solutions than consumers that are a lot older have been in the past…there’s a gateway for these consumers to technical advancements, because they believe it aligns with their values.”

Adds Mark Matlock, senior vice president of food research at Archer Daniels Midland Company: “To me, it’s really refreshing to have some consumers who are embracing technology to this degree, to the extent that they may lead the mainstream their direction.”

Battling Land Use Challenges

As the global population grows, the great challenge to the environment over the next decade will be making more food with less space.

The average American consumes 215 pounds of meat a year. Raising that meat uses 32 million acres of land, and produces 82 million metric tons of greenhouse emissions.

“The real challenge for the planet is not going to be ‘Are we going to have enough oil or carbohydrates?’ it’s ‘Are we going to have enough protein?’” Matlock said. “We create protein the way a cow creates protein. … we have to think: where are our rare resources going to be put?”

A third of the corn crop grown in America feeds livestock.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science