Reducing Wine’s Alcohol Content

Can you make wine with lower alcohol content? Researchers at Washington State University think so. They are growing wild in a lab to study how the yeasts behave and affect flavor and alcohol levels.

Yeasts used in winemaking — typically Saccharomyces — ferment by consuming the sugars in grapes, producing alcohol. If the grapes have higher sugar levels, they may produce wine with a higher alcohol percentage. But higher alcohol can have a range of negative consequences — bitter taste, incomplete fermentation leaving residual sugar and even higher taxes for the winemaker. WSU researchers hope, by perfecting wild non-Saccharomyces yeast strains, they can help the state’s winemakers better control the fermentation process, and reap the benefits of lower alcohol percentages.

Read more (Daily Evergreen)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Egypt’s 5,000-year-old Brewery

Archaeologists from NYU and Princeton have uncovered the world’s oldest industrial-sized brewery. Located in southern Egypt near the Abydos ruins, the facility dates from 3000 B.C. Many of Egypt’s early kings were born in Abydos, so it’s assumed the brewery made ceremonial beer for ritual offerings and royal funerals.

“The fundamental significance of the Abydos brewery is its scale relative to anything else in early Egypt,” project co-leader Dr. Matthew Adams said. The brewery likely produced about 22,400 liters with each batch (possibly weekly.) “That is a huge amount of beer by any standard, even in modern terms. It’s absolutely unique.”

Read more (Wine Spectator)

- Published in Science

An Irresistible Appeal

Scientists at Caltech , using fermented juice as bait have discovered that a fruit fly can travel six million times its body length in search of food.

Flies were lured by “a tantalizing cocktail of fermenting apple juice and champagne yeast produces carbon dioxide and ethanol, which are irresistible to a fruit fly.” Scientists released buckets of fruit flies on a dry lakebed in California’s Mojave Desert, far away from any other tempting food source.

The team is studying how far the flies would travel to a food source. Certain species of fruit flies are invasive and can cause significant agricultural damage. Their results will be published in the April issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Read more (Caltech)

- Published in Science

Solving Illnesses with Fermentation?

Scientists in Russia and Egypt have developed a functional drink that’s been proven to combat anemia and malnutrition. The juice is made from beet extract, milk and probiotic bacterial strains. The scientists developed a quinoa bread, too. The goal is to keep the beverage and bread affordably priced and get them offered at grocery stores internationally.

“One should bear in mind that we are not creating a medicine, but a natural, functional food product,” said Sobhi Ahmed Azab Al-Suhaimi, professor in the Department of Technology at South Ural State University (SUSU) in Russia. “However, this juice can make up for the lack of iron, zinc, manganese and calcium in the body. One serving of the drink will contain the whole rate [sic] of minerals. Its carbohydrate content is low. Fermented juice will help to overcome anemia and to improve digestion due to probiotics.”

Scientists at SUSU worked with scientists at the University of Alexandria in Egypt. Their findings were published in the Journal of Food Processing and Preservation and Plants.

Read more (Phys.org)

The Future of Fermentation Biotechnology

Leaders in the biotechnology industry are calling fermentation “Agricultural 2.0.” As consumers continue to seek alternative protein and dairy options, more biotech companies are using fermentation to produce alt-proteins. Ricky Cassini, co-founder and CEO of natural food colourant start-up Michroma, says: “The fermentation space is thriving and there is a lot of progress around this technology.”

Here are three expected developments in fermentation processing this year:

- More dairy-free cheese products will enter the market.

- Price points for alternative proteins will drop as more players enter the market.

- Regulatory issues and naming conventions will gain in significance.

Read more (Food Navigator)

Microbes & Chocolate’s Flavor

Love the rich flavor of chocolate? Thank microbes. Scientists are researching how fermentation affects the flavor of chocolate. An article in Scientific American details how a giant cacao seed pod naturally ferments.

Cacao has a wild fermentation, meaning the farmers who harvest the pods “rely on natural microbes in the environment to create unique, local flavors.” Just as grapes take on regional terroir (the characteristic flavor imparted by a place), “these wild microbes, combined with each farmer’s particular process, confer terroir on beans fermented in each location.” Demand for high-quality cacao beans is growing, and producers who make small-batch chocolate with distinctive flavors also are seeing sales growth.

Read more (Scientific American)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Fermenting — in Space?

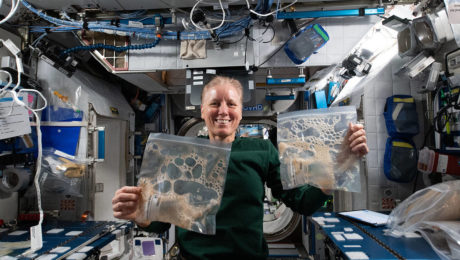

Microbes that coexist on plants influence a crop’s size, shape, color, flavor and yield. What would these microbes do in microgravity? The International Space Station (ISS) is testing to find these results.

Flight engineer Shannon Walker (pictured) shows sample bags collected for the Grape Juice Fermentation in Microgravity Aboard ISS study. Astronauts will observe the fermentation process, measuring microbial differences. Back on earth, a matching, control sample is being observed in an environmental control chamber that mimics the ISS ambient temperature. The space and earth samples then will be analyzed for changes. Both flight and ground control samples are analyzed post-investigation for genetic change.

Read more (NASA)

“One Grain to Bind Them All”

A new study on kefir found that the individual dominant species of Lactobacillus bacteria in kefir grains cannot survive in milk on their own. The bacteria need one another to create the fermented dairy drink, “feeding on each other’s metabolites in the kefir culture.”

The research, conducted by EMBL (Europe’s laboratory for life and sciences) and Cambridge University’s Patil group and published in Nature Microbiology, illustrates a dynamic of microbes that had eluded scientists. Though scientists knew microorganisms live in communities and depend on each other to survive, “mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited,” according to a press release on the research.

“Cooperation allows them to do something they couldn’t do alone,” says Kiran Patil, group leader and author of the paper. “It is particularly fascinating how L. kefiranofaciens, which dominates the kefir community, uses kefir grains to bind together all other microbes that it needs to survive — much like the ruling ring of the Lord of the Rings. One grain to bind them all.”

To make kefir, it takes a team. A team of microbes.

The group studied 15 samples of kefir, one of the world’s oldest fermented food products. Below are highlights from a press release on the published results.

A Model of Microbial Interaction

Kefir first became popular centuries ago in Eastern Europe, Israel, and areas in and around Russia. It is composed of ‘grains’ that look like small pieces of cauliflower and have fermented in milk to produce a probiotic drink composed of bacteria and yeasts.

“People were storing milk in sheepskins and noticed these grains that emerged kept their milk from spoiling, so they could store it longer,” says Sonja Blasche, a postdoc in the Patil group and an author of the paper. “Because milk spoils fairly easily, finding a way to store it longer was of huge value.”

To make kefir, you need kefir grains, which must come from another batch of kefir. They cannot be made artificially. The grains are added to milk, to ferment and grow. Approximately 24 to 48 hours later (or, in the case of this research, 90 hours later), the kefir grains have consumed the available nutrients. The grains have grown in size and number, and are removed and added to fresh milk — to begin the process anew.

For scientists, kefir is more than just a healthy beverage: it’s an easy-to-culture model microbial community for studying metabolic interactions. And while kefir is quite similar to yogurt in many ways – both are fermented or cultured dairy products full of ‘probiotics’ – kefir’s microbial community is far larger, including not just bacterial cultures but also yeast.

A “Goldilocks Zone”

While scientists know that microorganisms often live in communities and depend on their fellow community members for survival, mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited. Laboratory models historically have been limited to two or three microbial species, so kefir offers – as Patil describes – a ‘Goldilocks zone’ of complexity that is not too small (around 40 species), yet not too unwieldy to study in detail.

Blasche started this research by gathering kefir samples from several sources. Though most were obtained in Germany, they may have originated elsewhere, grown from kefir grains passed down through the years..

“Our first step was to look at how the samples grow. Kefir microbial communities have many member species with individual growth patterns that adapt to their current environment. This means fast- and slow-growing species and some that alter their speed according to nutrient availability,” Blasche says. “This is not unique to the kefir community. However, the kefir community had a lot of lead time for coevolution to bring it to perfection, as they have stuck together for a long time already.”

Cooperation is key

Finding out the extent and nature of cooperation among kefir microbes was far from straightforward. Researchers combined a variety of state-of-the-art methods, such as metabolomics (studying metabolites’ chemical processes), transcriptomics (studying the genome-produced RNA transcripts) and mathematical modelling. These processes revealed not only key molecular interaction agents like amino acids, but also the contrasting species dynamics between grains and milk.

“The kefir grain acts as a base camp for the kefir community, from which community members colonise the milk in a complex yet organised and cooperative manner,” Patil says. “We see this phenomenon in kefir, and then we see it’s not limited to kefir. If you look at the whole world of microbiomes, cooperation is also a key to their structure and function.”

In fact, in another paper from Patil’s group (in collaboration with EMBL’s Bork group) in Nature Ecology and Evolution, scientists combined data from thousands of microbial communities across the globe – from in soil to in the human gut – to understand similar cooperative relationships. In this second paper, the researchers used advanced metabolic modelling to show that the co-occurring groups of bacteria, groups that are frequently found together in different habitats, are either highly competitive or highly cooperative. This stark polarization hadn’t been observed before, and sheds light on evolutionary processes that shape microbial ecosystems. While both competitive and cooperative communities are prevalent, the cooperators seem to be more successful in terms of higher abundance and occupying diverse habitats — stronger together!

Chocolate’s Beer Roots

Chocolate beer sounds like a faddish flavor, but its roots run deep. Pre-Columbian Mesoamericans fermented cacao fruit to make a beer-like drink called chicha.

“Chicha is usually made from corn, but there are regional variations made from other new-world plants like potatoes, peanuts and cacao beans,” reads an article from The Seattle Times. Chicha was studied by archaeology professors at Cornell and Berkeley who found “The roots of the modern chocolate industry can be traced back to this primitive fermented drink.”

Read more (The Seattle Times)

Primates & Fermented Food

Humans have been fermenting for thousands of years; now, an anthropologist has published evidence that several other primate species also feed on fermented food.

Katherine Amato, at Northwestern University, compiled evidence from 151 biologists who study the feeding habits of 40 primate species from Asia, Africa and the Americas. Fifteen of those species consume fruit in the late stages of fermentation, and thatermented fruit makes up 3% of their diet. Though the scale is small, the evolutionary roots are interesting.

“Of the 44 types of fruit eaten in an advanced state of fermentation, 16 had tough husks that the animals could not easily open unless they were first fermented, and 25 contained digestion-impeding or toxic chemicals like tannins and alkaloids that fermentation tends to destroy,” reads an article in The Economist on the research.

It continues: “Several of the fermented-fruit-eating primates alive today split off from the line that leads to people well over 10m years ago. Presumably, they have evolved their own genetic arrangements for dealing with fermentation products and the microbes that produce them. Nevertheless, Dr. Amato’s work suggests that human beings’ love of the fermented does, indeed, have deep evolutionary roots.”

Read more (The Economist)

- Published in Science