Washington Post Article Explores Microbes and Fermentation Science

“Science is here to explain why fermenting vegetables is not only perfectly safe but also surprisingly easy and rewarding. Spoiler: Microbes do most of the work.

In our hyper-Pasteurian, expiration date-driven era, it might be difficult to relinquish control over our food to these mysterious forces. But a small measure of understanding yields rich rewards: crisp classic sauerkraut, warmly tart beets, bright preserved lemons and just about anything else you can dream up.” Katherine Harmon Courage writes in her article for the Washington Post “Eat Voraciously” section that fermentation adds a depth to fruits and vegetables. Harmon Courage, author of the book “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome”

Read more (Washington Post)

- Published in Science

Fermented Foods Follow Trends in Ethnic, Earthy and Floral Flavors

2020 is the year of the adventurous eater. A new survey reveals 74% of people love to discover new flavors. The Innova Trends Survey highlights botanicals, spices and herbs as popular flavors that will drive the food and beverage market in the new year. Innova calls these trending ingredients as “functionally flavorful.”

Fermented food brands are active in this regard. Kombucha brands are adding more botanical flavoring to their beverages, and fermented vegetable products are experimenting with unique spice and herb combinations. Flavor is still the No. 1 factor for consumers when buying food and beverages. Fermented food brands can use the trending ingredients of 2020 to develop new products and experiment with new flavor combinations.

“Ingredients have become the stars of many products,” says Lu Ann Williams, Innova Market Insights Director of Insights & Innovation. The industry, she notes, is experimenting with more unusual ingredients to the delight of customers.

Fermented food brands can use 2020’s most popular ingredients as they develop new products. One in two consumers associate floral flavors with freshness, and they associate herbal flavors with healthiness. Flavor is still “the No. 1 factor of importance when buying food and beverages.”

Below is a breakdown of the ingredients consumers want in the New Year.

Ethnic

Today’s consumers don’t just want to have food, they want to experience their food. Innova refers to this as living vs. having.

“Consumers are really living and focusing more on experiences, and a big part of that is food and where it comes from,” Williams adds. “Consumers are also looking for richer experiences. You can have Mexican food or you can have authentic Mexican food. And you definitely have a richer experience with authentic Mexican food with a beer paired with the product, with ingredients that came from Mexico.”

Evidence that globalization is changing food, six in 10 U.S. and U.K. consumers say they “love to discover flavors of other cultures.” There was a 65% growth in food and beverages with ethnic flavors. Products with the biggest growth rate have Mediterranean and Far Eastern flavors. Meat, fish, eggs, sauces and seasonings lead the ethnic flavor categories.

Earthy

The growing sect of health-conscious consumers want green, earthy flavors. Matcha, seaweed ashwagandha, turmeric and mushroom are all trending ingredients.

Fermented food brands shouldn’t hesitate to use bitter ingredients. Consumers more and more are embracing green vegetables with bitter flavors. Spinach, kale, celery and Brussels sprouts are ingredients used in product launches.

“Bitter-toned beverages are also on trend, with gins particularly popular over the past few years, and now seeing further differentiation via a growing variation in flavors, colors and formats,” according to Innova.

Floral

Thanks to the plant-based, natural, organic, healthy eating revolution, consumers are buying food and drink products with botanical, floral flavors. These are becoming more common in beverages, especially kombucha.

Bell Flavors and Fragrances EMEA launched a concept “Feel Nature’s Variety,” capitalizing on the trend. Chamomile and lavender are two of the most popular floral flavors.

“Although many emerging botanicals need more scientific investigation to support anecdotal evidence, many consumers trust ancient, traditional herbals,” according to an article in Prepared Foods.

Spicy

Consumer interest in spicy ingredients has increased 10 years in a row, according to global flavoring company Kalsec. More than 22,000 new hot and spicy products were launched in 207, while 18,000 hot and spicy products were launched in 2016.

“I think the trend has gone from shaking a bit of hot sauce on something to give it some heat to present day where consumers have a better understanding of how chili peppers can add depth and layering of both heat and flavor,” says Hadley Katzenbach, culinary development chef at food company Southeastern Mills.

Spicy ingredients gochujang (a red chili paste) and sriracha (a hot sauce) has grown about 50% in condiments and sauces, with mole, harissa and sambal following. Spicy peppers, including peri peri, serrano, guajillo, anaheim, pasilla and arbol, are also growing.

- Published in Business

Fermentation One of Defining Food Movements from Past Decade

Food movements from the past decade have changed how we are eating. Fermenting is one of the trend-defining innovations (and resurrections), according to a list by The Sunday Times in Britain. The article, titled “We foraged, we fermented, we went vegan” — the decade that changed the way we eat,” highlights the “real increase in locality and seasonality; a revival of the crafts of foraging and pickling and fermenting.” Author Marina O’Loughlin’s other food moments from the past 10 years: diners desiring independent restaurants instead of chains, an explosion of regional food (think Sichaunese or Hunanese restaurants instead of Asian), “dinner got cool” with food festivals and food trucks, veganism turned mainstream (same with nut milk, alternative meat products, zero waste and organic produce) and people are avoiding imported ingredients. Media is changing the restaurant scene, too. Netflix, The Food Channel and social media turned food photos into art.

Read more (The Sunday Times)

- Published in Business

Tempeh Booms, Becomes Tofurky’s Fastest-Growing Product Lines

Civil Eats declares: “Tempeh, the ‘OG of Fermented Foods,’ Is Having a Moment.” More artisanal tempeh producers are selling around the country, and restaurants are beginning to sell tempeh-based dishes. The founder of Tofurky (Seth Tibbott) says tempeh is one of the company’s fastest-growing product lines, increasing 17% from 2017 to 2018. Pictured is Tibbot in front of his first tempeh incubator, in 1980.

Read more (Civil Eats)

- Published in Business

Fermentation: Ingredient of the Future?

Is fermentation the ingredient of the future? As more consumers fear technologically-processed food, manufacturers are turning to ancient processing methods to make ingredients. Nutritional Outlook published an interesting article detailing how manufacturers are using fermentation to extract ingredients from foods. It’s a sustainable solution that produces ingredients like MSG, cultured dextrose and the sugar alcohol erythritol. Erythritol, for example, is produced by some fruits and mushrooms in very small quantities. But by fermenting the fruits and vegetables, an economical, high-quality sweetener is produced. The article notes “in an environment that prizes transparency, fermentation present a refreshingly open book. …Fermentation may not strike the romantic chord of tugging an ingredient from the soil, but it’s unambiguously traceable, quantifiable, and safe.” Brands like Impossible Foods (plant-based meat) and EverSweet (sweetener) both use fermentation to extract ingredients.

Read more (Nutritional Outlook)

- Published in Business

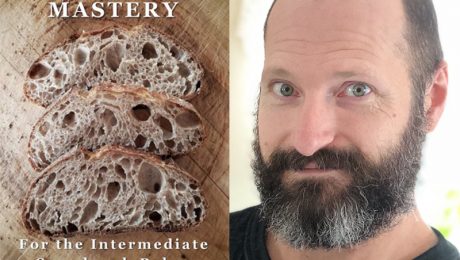

Q&A with Trevor Wilson, Author of “Open Crumb Mastery”

Ask Trevor Wilson how to bake a perfect sourdough boule and Wilson will happily spill his secrets. A rare breed in the realm of professional bakers, Wilson aims to enlighten everyone from hobbyists to master fermenters in the art of creating a great sourdough.

“It’s a fascinating thing. The idea that a simple mixture of flour and water can house a symbiotic culture of wild yeast and bacteria, and that this mixture can be used to leaven bread entirely without the aid of commercial yeast seems astounding to me,” says Wilson, author of the book “Open Crumb Mastery” and the kneading hands behind the blog Breadwerk. His popular Instagram account is full of close-up videos of a knife cutting into a steamy sourdough crust and magazine-worthy images of a gorgeous inner crumb.

“Even after all these years, I still get excited at the thought. There’s just so many possibilities! Every sourdough culture is unique, and therefore the breads made from these cultures are unique as well. I’ve worked with many different starters over the course of my career, and the range of different flavors that can be achieved is simply mind-blowing. Sourdough is more than just a style of bread, it’s a process. A craft. A way of life, really.”

Wilson quit his computer drafting job nearly 20 years ago to bake full-time. He spent 10 years baking at Klingers Bread Company in Vermont, an experience he says was “better education than any baking school could ever provide.” His refreshing philosophy on baking is “that good bread is more than just nutrients and technique — it’s the attention and care you put into it.”

Below, a Q&A with Wilson from his home on the a small island off the coast of Vermont.

How did you first become interested in sourdough baking?

It was actually quite by chance. I was flipping channels on the television when I happened upon a show called “Baking Bread with Father Dominic.” Here was this Benedictine Monk – robes and all – baking bread by hand on public broadcasting. I was drawn in immediately! There was just something so appealing about the simplicity and tradition of it (not to mention the fun of getting your hands deep into the dough). I had to give it a try!

The very first chance I had I decided to make a cinnamon raisin loaf. It was for the family Christmas gathering. I just used the ingredients on hand at my mom’s house – cheap bleached all-purpose flour and a package of long-expired yeast that had been sitting in the pantry for years. As you might imagine, it came out terrible. Dense and underbaked. Like a brick. It didn’t rise at all. Nobody even touched it. But it didn’t matter. I was hooked!

I started baking bread every day – my own recipes because I just have to tinker with things like that – and read everything I could get my hands on. It wasn’t long before I discovered sourdough and sourdough starters. That’s when I truly became obsessed.

Tell me what intrigues you about sourdough.

It’s a fascinating thing. The idea that a simple mixture of flour and water can house a symbiotic culture of wild yeast and bacteria, and that this mixture can be used to leaven bread entirely without the aid of commercial yeast seems astounding to me. Even after all these years, I still get excited at the thought. There’s just so many possibilities! Every sourdough culture is unique, and therefore the breads made from these cultures are unique as well. I’ve worked with many different starters over the course of my career, and the range of different flavors that can be achieved is simply mind-blowing. Sourdough is more than just a style of bread, it’s a process. A craft. A way of life, really.

How did you get your start in artisan bread baking? You’ve worked for multiple artisan bread bakers in Vermont, like Klingers Bread Company and O Bread.

Shortly after I got hooked on bread baking, I decided that this was it – this is how I wanted to spend my life. I was certain of it. Even though I had recently graduated tech school and was ready to start my career as a computer aided drafter – something which I actually really enjoyed – there was no question in my mind that bread baking was my calling. There was just one problem . . . I couldn’t bake a decent loaf for the life of me!

Since I had no clue what I was doing, I figured the first thing I should do is get a clue. I knew I could go back to school and study bread and pastry arts. But I didn’t really care much about pastry at the time, and it seemed rather foolish to pay to learn a skill when I could just get a job at a bakery and get paid to learn that skill instead. So that’s what I did. I applied to every bakery in the area, and I was fortunate that Klingers Bread Company took me in and trained me.

I say I was fortunate because at the time (back in 2000) they were one of the few local bakeries that focused primarily on sourdough breads. And that’s what I was most interested in learning. The ten years I spent with them was better education than any baking school could ever provide. Learning to bake bread at high volume under the constraints of ever-changing production conditions, schedules and demands will teach you so much about the process, the craft, and the business. I wouldn’t trade those days for the world.

Where are you currently working as a baker?

Currently I’m baking at home! But not for production. Primarily it’s for educational purposes (and for fun). My business these days is mainly online. I probably spend more time in front of the computer than at my bench. There are pros and cons to this. It’s nice that I’m able to set my own work schedule and be my own boss (and that I don’t need to wake up at 2 a.m. anymore), but I miss the camaraderie of the bakery and the joys of production baking.

Your blog is full of great insights. I love your philosophy that good bread is more than just nutrients and technique – it’s the attention and care you put into it. Tell me more about that.

I believe that the value of a food is determined by more than just the quality of its ingredients or the recipe with which it is made. There is a subtle and intangible “something” that can be added as well – if the food is made with care and attention, that is. Call it a piece of soul, if you will. This is especially true for something as dynamic and responsive as sourdough. A baker who bakes with heart adds a piece of soul to every loaf. That is the true nourishment of sourdough bread.

Tell me about your book, “Open Crumb Mastery.” It’s a guide for intermediate sourdough bakers.

Well, I wrote it to answer one of the most common questions in bread baking, “How do I get an open crumb?” It seemed to me that most of the answers to this question were either entirely wrong or, at best, severely lacking in nuance. There was actually very little literature on the topic, and what there was usually just glossed over the intricacies of the subject. Simply adding more water to your dough – the answer most commonly given – is terrible advice for newer bakers. They have a hard enough time handling dough as it is, how is making it even wetter and stickier going to help them? What was needed was a book that actually did justice to the topic, and since no one else had written such a book, I figured I might as well do it myself.

I aimed the book at the “intermediate” baker primarily because I didn’t want to waste space covering the same old information that is covered in every other bread book out there. How many times do we need to read the same five day method for creating a sourdough starter? How many times do we need to rehash the same information about ingredients and procedure? The reason all these books covered the same topics over and over again is because they each had to provide information with the beginner in mind. But the problem is that by the time you’ve covered everything the beginner needs to know, you’ve practically run out of space! All that’s left is the recipe section! There’s no room for depth of discussion. Because I self-published my book, I could write whatever I wanted. So I skipped all that and went straight to the good stuff.

You just released your second edition. Tell me what is new in this updated book.

There’s actually quite a bit of new material – almost 100 pages worth (including plenty of new pictures since the first edition was kind of lacking in that department). The main addition to the book comes in the form of a new section dedicated to understanding how the methods discussed in the previous sections relate to other loaf qualities such as shape, height, and volume. There is more to a loaf than just its crumb. The original edition just lightly touched upon these topics; the new edition gives them their due. Along with some other additions (such as a discussion of whole grain, and a couple new crumb analyses focusing on retarding bulk fermentation), the new material provides a more complete picture regarding how the variables of technique and method affect the entirety of the final product.

Describe the open crumb technique.

That’s a tough one. It’s such a deep discussion that I could never do it justice in an interview alone. That’s why I wrote a book! My main point is that open crumb is primarily a matter of fermentation and dough handling. Hydration, while important, is only a distant third.

You said “Open crumb is 80% fermentation and handling.” Tell me more about that.

It seems to me that much in life follows the Pareto Principle – that 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. Bread baking is no exception. When it comes to achieving an open crumb, fermentation and dough handling will provide you with 80% of the effect. Therefore, it seems prudent to me that a baker interested in open crumb should spend the bulk of their time learning the skills of fermentation and handling. That will provide the highest return on time invested.

And make no mistake, these are skills. Skill takes time to develop. Practice is paramount. Only through experience will a baker learn to master fermentation and dough handling. But it’s a necessary and vital part of the craft. There’s really no way around it. For any baker that’s seeking to achieve an open crumb, they must start with fermentation and dough handling.

What makes a fermented sourdough unique from other breads?

It’s all about that sourdough culture! The starter is the heart and soul of it all. It provides qualities to bread that commercial baker’s yeast simply can’t replicate. Now whether that’s for better or worse is a matter of opinion. Not every style of bread benefits from the use of sourdough. There’s a large world of bread out there, and yeast breads certainly have their place.

But sourdough has its place as well. And judging by the growing interest, its place seems to be expanding day by day. For good reason, I think. Sourdough possesses a combination of crust, crumb and flavor that is difficult – if not near impossible – to achieve with baker’s yeast alone. Especially flavor. It’s just so much more complex than yeast bread. Deeper. More interesting. Intriguing, even. The acids and other flavor and aroma compounds generated by a sourdough starter are what make sourdough breads truly stand out. Comparable crust and crumb might be had with yeast breads that are long-fermented and skillfully made, but the flavor of sourdough can’t be copied and can’t be faked. Only the real thing will do.

How do you ferment your sourdough?

Many different ways. As I often say, the method makes the bread. How you choose to ferment your dough will have a huge impact on the bread’s flavor, as well as many other qualities of the final loaf. Different methods of managing fermentation will therefore result in different breads. So the manner in which you choose to ferment a dough is dependent upon what kind of bread you are making, and what qualities you are seeking in a loaf. When you include other variables such as folding methods/schedules, shaping techniques, starter maintenance routine, etc. then the possibilities really are endless. It’s up to each baker to ferment and handle their dough in a way that works best for them and their needs.

Tell me about the sourdough starter you use.

That’s a tricky question, because I use many different starters. In fact, you can say I have a bit of an addiction. I love trying out new starters – and I have a fridge full of them! Some are better suited for certain flavors or styles of bread than others, but still, I often bring different starters into rotation based on nothing more than whim. I just like playing around with them. Many I’ve created myself, but quite a few I’ve purchased as well.

I’d say my favorite starter (you could call it my main starter since I use it more often than any of the others) is an “Alaskan” starter that I got from the last place I worked. They had purchased it online but hadn’t had any success in getting it active. I took it home and brought it to life, and I knew it was a keeper from the first test loaf I ever made with it. It practically brought tears to my eyes. The flavor was so close to the old Pioneer Sourdough I’d grown up eating in Southern California that I simply couldn’t believe it. It was a flavor I’d been searching for — and had yet to find — since I first started baking sourdough. That old bakery closed a long time ago and so I thought I might never experience that taste again. It’s a bit of a fickle starter, and I don’t always get that perfect flavor from it, but when I do it’s a glorious thing.

More and more retail news show sales of sourdough bread are increasing. Why do you think more people are buying sourdough bread?

Over the last 35 years or so, there’s been a strong “push” by bakers themselves to bring awareness to this style of bread. The old methods of sourdough baking had practically gone extinct in many parts of the world (though they were still thriving in others). This was especially true in the United States, where factory-made sandwich bread had almost completely taken over the market. For many, sourdough was something either long forgotten or completely unknown. For those bakers back in the day who were making bread the old way, it was quite the struggle to find customers.

Fortunately, over the years they – and those who followed – have managed to bring awareness to the pleasures and benefits of sourdough bread. It wasn’t always an easy sell. But through education and promotion, sourdough is now part of the scene and here to stay. You might even say it’s become rather trendy. The reasons are many: nutrition and health, flavor, crust, crumb, history and tradition, etc. It seems to me that artisan sourdough bread is the food fashion of the moment, but then, I might be a bit biased here.

Do you think consumers awareness of fermented foods is increasing?

Awareness of fermented foods is definitely increasing. Quite drastically, I might add. It seems that fermented foods are everywhere nowadays, with more and more popping up on the shelf every day. And that’s a good thing as far as I’m concerned. The more that folks are exposed to these foods, the more they will be enjoyed — and eventually adopted as a natural part of the cuisine. That brings more interest, more variety, and more flavor to the food scene.

What challenges do fermented food producers face?

There are many challenges faced by the current crop of fermented food producers, and different industries face different challenges. Probably one of the bigger challenges that crosses over many categories of fermented foods is simply getting consumers – many of whom have had little exposure to these types of foods – to open their minds and give fermented foods a try. This is especially true for producers that market raw ferments with live cultures. Most of us have grown up in a world of pasteurization and sterilization. The idea of a raw fermented product – though perfectly natural throughout most of history – may seem unnatural to those who have no history with it. Needless to say, educating the market will be an ongoing challenge.

Another major challenge these days is simply the matter of competition. With more and more producers jumping onto the fermented foods bandwagon, competition keeps growing and growing. Of course, this is regional and market based. So long as the market keeps growing, then there is more room for additional producers. But in places where the market has slowed, or that are already oversaturated with producers, expanding competition will cut into already slim profit margins.

I see this all the time in the baking industry. New artisan bakeries are constantly opening up on a daily basis. Many are (similarly) making a trendy style of dark, crusty, high-hydration bread. So it’s becoming more and more difficult for these bakeries to distinguish their product from all the rest (at least in the saturated urban areas). Baking is a hard business with slim margins, and it is made harder all the more when you have a bakery selling the same kind of bread on every corner. I fear that many of these bakers – even those who bake outstanding bread – will be forced to close shop in the not-too-distant future.

What are the fermented food industry strengths?

Its biggest strength is its growing popularity. As more and more folks are exposed to the wonderful variety and flavors of fermented foods, and as more become aware of their health and nutrition benefits, the good word will continue to spread. The market is growing rapidly, and will likely continue to do so for quite some time. Producers of fermented foods are well-positioned to grow their businesses as the industry continues to expand and evolve.

Where do you see the future of the fermented food industry?

It’s hard to say. I’ve spent an entire career in just one small segment of the industry. With “nose to the bench,” so to speak, I’ve had a rather limited view of the fermented food industry as a whole. I’m no trend forecaster. It seems to me that authors such as Michael Pollan, Sally Fallon, and Sandor Katz (to name a few) were instrumental in bringing us to this place of awareness and appreciation for wholesome and traditional foods that we now find ourselves in today. Who’ll step up next and where do we go from here? That’s the million-dollar question.

What’s your advice to other entrepreneurs starting a fermentation brand?

Know your product, know your market, know your margins.

The first one is usually the easiest – most of the folks that are jumping into the fermented food business are doing so precisely because they are so passionate about their product. No need to elaborate this point.

The second is vital to those who actually wish to sell a product. Who is your target customer? Where are they? Why should they buy from you? Are you selling wholesale or retail? Or both? Are you selling at farmer’s markets? Whole foods markets? Supermarkets? Are you selling to restaurants, delis, or other food preparation establishments? Are you selling online? In catalogs? At local farm stands? Who’s your competition? Where do they sell? How does your product differ from theirs? Why should a customer purchase your product instead of theirs? What is your value proposition?

When you have answers to these questions (and many more) then you can begin to understand your market. Understanding your market helps you to understand how best to sell to it. Often times in the food business (particularly in craft foods), customers don’t just want to buy a product to eat. They’re looking for a higher value. Can you sell them that higher value? Can you sell them history and tradition? Can you sell them nutrition and health? Can you sell them a story, or a feeling, or an idea? Can you sell them a way of thinking? A way of life? A community? The business that can sell these things is the business that succeeds.

The third point speaks to the bottom line. So many new entrepreneurs jump into the food business out of passion and idealism, but they forget the business part in “food business.” It is a business, and don’t forget it. If you can’t turn a profit or manage cashflow, then you won’t be in business very long. From an operations standpoint, efficient production is profitable production. So focus on efficiency.

Inefficient production includes things like making too many different products in order to appeal to every taste instead of focusing on and maximizing the big sellers (Pareto Principle again), using wildly different production methods for different products when you could combine and/or streamline the processes instead (i.e. completely different recipes for different products instead of using just one or two base recipes that can then have specialty ingredients simply added to them in order to create different products), and poorly designed production environments that don’t allow for economy of motion (if you’re running around all over the place like a chicken with its head cut off then you may need to improve your floor layout). Those are just a few examples of inefficient production.

Be especially careful how you grow and never lose sight of your margins. Many new business owners are too quick to accept large accounts in an effort to expand their business – especially if they’re struggling. But far too often they come to regret that decision, particularly smaller craft producers. Large operations are built to benefit from economies of scale, but small local producers often struggle due to limitations in batch size, work space, and available labor. So accepting large accounts results in more batches which results in more labor. As labor costs go up, profit margins go down. The end result is a lot more work for just a little bit more money. Quality tends to go down, capacity gets maxed out for little added profit, and cashflow gets tied up in additional inventory. Now you’re stuck, unable to pay bills, and unable to take on new or more profitable accounts. Avoid that situation like the plague.

It’s pretty simple really; a dollar saved is a dollar kept whereas a dollar earned is but a dime kept. That’s margin. Efficiency saves you dollars. Responsible cost cutting saves you dollars (so long as it doesn’t come at the cost of quality or efficiency). And intelligent growth saves you dollars. If you can produce efficiently, earn a profit, and effectively manage growth and cash flow, then you’ll do just fine.

- Published in Food & Flavor

New Food Laws Taking Effect in 2020

Thousands of new state laws were passed across America this year, and dozens affect fermentation businesses — small and large — as well as home fermenters.

Government agencies are loosening some strict health code and alcohol regulations, laws that made running an artisanal business difficult. There are also new opportunities being created that allow craft breweries to expand their operations, such as entertainment districts where beer can be sold and enjoyed legally.

Read on for the breakdown of 2019 food laws passed in each state

Alaska

SB16 — Expands state alcohol licenses to include recreational areas. After the Alaska Alcoholic Beverage Control Board began cracking down on alcohol licenses in 2017, several recreational sites were denied licenses to sell alcohol. The bill, known as “Save the Alaska State Fair Act,” now expands license types to the state fair, ski areas, bowling alleys and tourist operations.

Arizona

HB2178 — Removes red tape for small ice cream stores and other milk product businesses to manufacture and sell dairy products. The bill, called the “Ice Cream Freedom Act,” allows smaller mom and pop businesses to make milk-based products without complying with state regulations designed for large dairy manufacturers.

Arkansas

HB1407 — Prohibits false labeling on agricultural products edible by humans. That includes misleading labels, like labeling agricultural products as a different kind of food or omitting required label information.

HB1556 — Ends the “undisclosed and ongoing investigations” of the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board, the Alcoholic Beverage Control Division, and the Alcoholic Beverage Enforcement Division.

HB1590 — Limits the number off-premise sales of wine and liquor in the state to one permit for every 7,500 residents in the county or subdivision. Small farm wines are the exception to the new law.

HB1852 — Allows a microbrewery to operate in a dry county as a private club, without approval from the local governing body.

HB1853 — Amends the Local Food, Farms, and Jobs Acts to increase the amount of local farm and food products purchased by government agencies (like state parks and schools).

SB348 — Establishes a Hard Cider Manufacturing Permit. Cider brewers can apply for the annual $250 permit, authorizing the sale of hard cider. Producers may not sell more than 15,000 barrels of hard cider a year.

SB492 — Establishes temporary or permanent entertainment areas in wet counties where alcohol can be carried and consumed on the public streets and sidewalks.

California

AB205 — Revises the definition of beer to mean that beer may be produced using “honey, fruit, fruit juice, fruit concentrate, herbs, spices, and other food materials, and adjuncts in fermentation.”

AB377 — A follow-up to the state’s landmark California Homemade Food Act in 2018, the new bill would clarify the implementation process of last year’s bill. The California Home Food Act made it legal for home cooks to operate home-based food production facilities. The law, though, was only enacted if a county’s board of supervisors voted to opt-in to offer the permits. Only one county in California has opted in (Riverside). County health officials are avoiding singing on the bill because of potential food safety risks.

AB619 — Permits temporary food vendors at events to serve customers in reusable containers rather than disposable servingware. The “Bring Your Own Bill” also clarifies existing health code, allowing customers to bring their own reusable containers to restaurants for take-out.

AB792 — Establishes a minimum level of recycled content (50%) in plastic beverage bottles by 2035. The world’s strongest recycling requirement, the law would help reduce litter and boost demand for manufacturers to use recycled plastic materials.

AB1532 — Adds instructions on the elements of major food allergens and safe handling food practices to all food handler training courses.

Connecticut

HB5004 — Raises minimum wage to $15 by 2023.

HB6249 — Charges 10 cents for single-use plastic bags by 2021.

HB7424 — Raises sales tax from 6.35% to 7.35% for restaurant meals and prepared foods sold elsewhere, like in a grocery store. Also repeals the $250 biennial business entity tax.

Delaware

HB130 — Bans single-use plastic bags by 2021.

SB105 — Raises minimum wage to $15 by 2024.

HB125 — Facilitates growth and expansion of craft alcoholic beverage companies, raising amount of manufactured beer to 6 million barrels.

Florida

SB82 — Prohibits a municipality from regulating vegetable gardens on residential properties.

Idaho

HB134 — Regulates where beer and wine can be served, now including public plazas.

HB151 — Charges licensing fees for temporary food establishments based on the number of days open. Fees will gradually increase through 2022.

Illinois

HB3018 — Amends Food Handling Regulation Enforcement Act, requiring a restaurant prominently display signage indicating a guest’s food allergies must be communicated to the restaurant.

HB3440 — Allows customers to provide their own take-home containers when purchasing bulk items from grocery stores and other retailers.

HB2675 — An update to state liquor laws, the bill removes hurdles for craft distilleries to operate. Craft distilleries would be allowed to more widely distribute their products themselves, rather than distributing under the state’s three-tier liquor distribution system that separates producers, distributors and retailers.

SB1240 — Imposes a 7 cent tax on each plastic bag at checkout, with 2 cents staying with the retailers. The remaining 5 cents per bag would fix a statewide budget deficit.

Indiana

HB1518 — Creates a special alcohol permit for the Bottleworks District. The $300 million, 12-acre urban mixed-use development in the Coca-Cola building will serve as a culinary and entertainment hub in downtown Indianapolis.

Iowa

SF618 — Increases the limit on alcohol in beer from 5% to 6.25%.

SF323 — Canned cocktail and premixed drinks served in a metal can, up to 14% alcohol by volume, will now be regulated like beer.

Kentucky

HB311 — Requires proper labeling of cell-cultured meat products that are lab produced.

HB468 — Expands defined items permitted for sale by home-based processors.

Louisiana

HR251 — Designates week of September 23-29 as Louisiana Craft Brewer Week.

SB152 — Establishes definition for agriculture products. Prohibits anyone from mislabeling a meat edible to humans.

SR20 — Designates week of September 3-9th as Louisiana Craft Spirits Week.

Maine

LD289 — Prohibits stores from selling or distributing any disposable food containers that are made entirely or partially of polystyrene foam (Styrofoam).

LD454 — Provides funding and staffing needed to give local students and nutrition directors the resources needed to purchase and serve locally grown foods.

LD1433 — Bans two toxic, industrial chemicals (phthalates and PFAS) from food packaging. Maine becomes first state in the nation to ban the two chemicals.

LD1532 — Bans all single-use plastic bags in the state. Law will be enacted by April 2020, at which time shoppers can pay 5 cents for a plastic bag. Maine is the fourth state to pass a ban, joining California, New York and Hawaii.

LD1761 — Increases amount of barrels craft beer and hard cider manufacturers can produce in a year. The cap increased from 50,000 gallons to 930,000 gallons (approximately 30,000) barrels. The law also makes it easier for a small brewery to get out of a contract with a large distributor.

Maryland

SB596 — Defined mead as a beer for tax purposes.

HB1010 — Updates state beer laws by increasing taproom sales, production capabilities, self-distribution limits and hours of operation. Known as the Brewery Modernization Act, the law is aimed to create jobs and increase economic impact.

HB1080 — No restrictive franchise law provisions for brewers that produce 20,000 barrels a year or less.

HB1301 — Sales tax will be collected on Maryland buyers from online sellers, helping small businesses compete with online retailers.

Massachusetts

HB4111 — Raises minimum wage by 75 cents a year until it reaches $15 in 2023.

Michigan

HB4959 — Gives state Liquor Control Commission the power to seize beer, wine, mixed spirit and mixed wine drinks, in order to inspect for compliance with the state’s extraordinarily detailed and complex “liquor control” regulatory and license regime. Bill also repeals a one-year residency requirement imposed on applicants for a liquor wholesaler license, after the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a similar Tennessee law as a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause.

HB4961 — Prohibit licensed liquor manufacturers from requiring licensed wholesalers to give the manufacturer records related to the distribution of different brands, employee compensation or business operations that are not directly related to the distribution of the maker’s brands.

SB0320 — Eliminates mandate that businesses with a liquor license must post a regulatory compliance bond with the state.

Minnesota

HF1733 — Updates the state’s omnibus agriculture policy law, including: create a custom-exempt food handlers license for those handling products not for sale; extend the state’s Organic Advisory Task Force by five years; allow the agriculture department to waive farm milk storage limits is the case of hardship, emergency, or natural disaster, and modify milk/dairy labelling requirements; modify labelling for cheese made with unpasteurized milk; expand the agriculture department’s power to restrict food movement after an emergency declaration; modify eligibility and educational requirements for beginning farmer loans and tax credits.

Mississippi

SB2922 — Prohibits labeling non-meat products as meat, like animal cultures, plants and insects.

Montana

HB84 — Changes tax on wine to 27 cents per liter, and a tax on hard cider at 3.7 cents per liter.

SB358 — Raises alcohol license fee for resorts from $20,000 to $100,000 each.

Nebraska

LR13 — Establish and enforce definitions for plant-based milk and dairy. Proper product labeling would be enforced for milk and dairy food products that are “truthful, not misleading, and sufficient to different non-dairy derived beverages and food products.”

Nevada

SB345 — Authorizing pubs and certain wineries to transfer certain malt beverages and wine in bulk to an estate distillery; authorizing a wholesale dealer of liquor to make such a transfer; authorizing an estate distillery to receive malt beverages and wine in bulk for the purpose of distillation and blending; revising when certain spirits that are received or transferred in bulk are subject to taxation.

New Hampshire

HB598 — Establish a commission to study beer, wine, and liquor tourism in New Hampshire. The commission will specifically develop a plan for tourism, including establishing tourist liquor trails with signage along the highway, suggest changes to liquor laws that would enhance tourist experiences at state wineries, breweries and liquor manufacturers and suggest how to allow a “farm to table” dinner featuring New Hampshire produced food items and local alcoholic beverages.

HB642 — Defining ciders with alcohol content greater than 6% (but no more than 12%) as specialty beers.

New Jersey

A15 — Raises the state minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024, raising in $1 increments every year.

SB1057 — Establishes a loan program for capital expenses for vineyards and wineries in New Jersey.

New Mexico

SB149 — Change name of Alcohol and Gaming commission to Alcoholic Beverage Control Division.

SB413 — Allows breweries to: sell beer at 11 a.m. on Sundays; have private celebration permits for events like weddings and graduation parties; no minimum standards (50 barrels a year or 50 percent of all sales coming from beer brewed on site) for businesses to hold a small brewer license; eliminate excise tax, with breweries paying $.08 per gallon on the first 30,000 barrels produced.

New York

AB6019 — Encourage expansion of fresh fruits and vegetables in community gardens.

AB 8419 — Enacts the farm laborers fair labor practices act, granting collective bargaining rights, workers’ compensation and unemployment benefits to farm laborers

SB578 — New option for any brewer or distiller to file their taxes electronically.

SB1263 — Allows mead (honey-based wine) and braggot brewers to apply for a state farm meadery license. Similar to a farm winery, brewery, distillery and hard cider license, the law recognizes the boom in the craft beverage industry in the state. As a licensed meadery, mead-makers who use 100% New York honey will quality for additional benefits: offer onsite tastings, sell products by glass in their tasting rooms, sell takeout packages, offer other New York farm-produced beer, wine, cider and spirits.

SB3281 — Amends current Alcoholic Beverage Control law, authorizing the sale of cider, mead, braggot and wine at games of chance.

SB4812 — Amend current Alcoholic Beverage Control law, permitting New York State Fair concessionaires to issue a temporary State Liquor license to sell alcoholic beverages on the state fairgrounds.

SB5675 — Amend current Alcoholic Beverage Control law, authorizing issue of liquor license to a business located within 200 feet of a religious institution in multiple counties.

North Carolina

HB363 — Adds a third tier to the craft beer system — mid-level brewers. Now brewers can self-distribute 50,000 barrels of product. Called North Carolina’s Craft Beer Distribution & Modernization Act, the law also expands liquor licensing to college-level NCAA events, where drinking is currently unregulated. Currently, the law only applies to beer and wine.

North Dakota

HB1190 — Amend code to allow a winery to be issued a license without the previous requirements for how much wine is allowed to be produced in a year.

HB2079 — Amends code regarding pasteurized milk, authorizing a state milk sanitation rating and sampling surveillance officer for the rating and certification of milk and dairy products.

SB2343 — Adds microbrew pub as an official brewer licensee under city code. A microbrew pub may manufacture on the licensed premises, store, transport, sell to wholesale malt beverage licensees, and export no more than 10,000 barrels of malt beverages annually; sell malt beverages manufactured on the licensed premises; and sell alcoholic beverages regardless of source to consumers for consumption on the microbrew pub’s licensed premises. A microbrew pub may not engage in any wholesaling activities.

Oklahoma

SB544 — Requires limits on licensing fees for businesses who only sell at farmers markets.

SB608 — Requires manufacturers of the top 25 wine and spirit brands to sell their products to any state-licensed wholesaler. The law requires equal sales of the top brands, potentially creating a competitive market. The matter is currently being heard by the Supreme Court, as some businesses believe this eliminates a free market.

Oregon

HB3239 — Removes the limit of how many on-premises sales licenses that a distillery can have.

SB247 — Adds containers for kombucha and hard seltzer to the types of beverage containers covered by Oregon’s Bottle Bill. The Bottle Bill establishes laws that require stores and distributors to accept certain empty beverage containers and pay a 10-cent refund value for each container.

Pennsylvania

HB947 — Amends the Liquor Code established in 1951, to provide further definitions for licenses and regulations for liquor, alcohol and malt and brewed beverages.

Rhode Island

SB620 — Increases the amount of malt beverages that could be sold on premises at a craft brewery.

South Dakota

SB68 — Prohibits labeling cell-cultured protein as meat.

SB124 — Allows a retailer, carrying their own merchandise purchased from a wholesaler, to transport alcoholic beverages to the retailer’s licensed business.

Tennessee

SB358 — Requiring unpasteurized butter sold to the public must bear a warning on the package label. The warning was approved by the legislature and added to state code.

SB 1082 — Allows premises authorized to serve wine to also serve high alcohol content beer. Requires training for applicants for server permits, consisting of no less than 3.5 hours of alcohol awareness training. Clarifies premises authorized to sell alcoholic beverages to include tables and chairs outside the front wall of the licensee’s building.

Texas

HB1545 — Allows craft breweries to sell beer to-go in Texas. Though wineries have been able to sell to customers for years, breweries have been unable because of alcohol beverage code written in 1935.

HB4542 — Adds brewpub to local tax code for businesses involved in manufacturing and distribution of alcoholic beverages.

SB572 — Expands state cottage food law to include opportunities for people to make low-risk products in home kitchens and sell them to consumers. Cottage food products now include fermented products, pickled vegetables, acidified canned goods and frozen fruits and vegetables.

Utah

HB33 — Defines the term “produce” as a food that is: fruit, vegetable, mix of intact fruits and vegetables, mushroom, sprout from any seed source, peanut tree nut, or herb and a raw agricultural commodity. Known as the Utah Wholesome Food Act, the law also expands the definition of “food establishment” to include farms.

HB453 — Defines specific business that can have a recreational beer license, specifically banning karaoke bars and ax-throwing businesses from getting a license.

SB132 — Drops 3.2% beer in favor of 4% brew, allowing the stronger beers to be sold in grocery and convenience stores. Stronger beers would still be sold in liquor stores operated by the Utah Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control.

Vermont

SB113 — Bans single-use plastic bags on July 1, 2020 and requires a fee of at least 10 cents for paper bags. Bans polystyrene foam contains, plastic stirrers and plastic straws.

Virginia

HB1960 — Allows distillers to product and market low alcohol volume products.

HB2634 — Makes every “dry” county in the state a “wet” county. Allows sale of mixed beverages by licensed restaurants (and the Board of Directors of the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority) by any municipality. If the county, town or district holds a referendum and the majority vote prohibits alcohol sales, then alcohol sales are banned in that jurisdiction.

- Published in Business

Fermented Seaweed Products Use 2020’s Super Ingredient

Seaweed will be 2020’s super ingredient, according to Bloomberg. The regenerative ocean plant is being used by entrepreneurs in fermented food products like hot sauce, tea, alcoholic beverages and even kimchi and sauerkraut. Atlantic Sea Farms in Maine is the largest kelp aquaculture business in the U.S. and makes Sea-Chi (spicy marine version of kimchi) and Sea-Beet Kraut (beets, carrots and kelp). Atlantic Sea Farms, run by former diplomat Briana Warner, plants to expand its harvest and production from 250,000 pounds this year to 600,000 pounds in 2020.

Read more (Bloomberg)

- Published in Food & Flavor

U.S. Olive Growers Petition FDA to Adopt First-Ever Industry Standards

By: American Olive Oil Producers Association

The American Olive Oil Producers Association and Deoleo, the world’s largest producer of olive oil, submitted a citizen petition to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to adopt science-based, enforceable standards for olive oil.

“Buying quality extra virgin olive oil is hard, but not because there aren’t quality products on supermarket shelves. It’s because there are just no rules to stop bad actors from misrepresenting what they’re selling,” said Adam Englehardt, Chairman of the American Olive Oil Producers Association.

“It was in this vacuum that California adopted a state-based grading and labeling standard in 2014. Family farms like mine supported those regulations because it allowed growers and producers a real opportunity to compete. A half-decade later our state is known around the world for its commitment to quality,” said Englehardt.

The new standards for olive oil, which FDA would be empowered to promulgate after a final rule pending a public comment period, would mark the first time the federal government has regulated the category. Citizen petitions for Standards Of Identity have resulted previously in the adoption of regulations for a variety of other food products.

Stakeholders involved are confident that the petition demonstrates the need to adopt the proposed science-based olive oil standards to provide honest and fair dealings in the interest of consumers while promoting a vibrant and competitive industry.

“We believe consumers have the right to know what they’re buying, but the absence of an enforceable regulatory environment makes this difficult,” said Ignacio Silva, President and CEO of Deoleo. “The petition provides an incredible opportunity to improve quality across the category and most importantly, it will restore consumer trust in olive oil. We support science-based grading standards because we’re committed to quality. It’s just that simple.”

A 2015 investigation by the National Consumers League into olive oil mislabeling found six of eleven national brands had misrepresented quality grades to consumers. A separate, four-year audit of the category between 2015 and 2019 found half of all products available to consumers today failed to meet international quality standards.

Consumers deserve to know what they are buying and should be confident that they are receiving the value and health benefits that correspond with the quality grade of olive oil they desire. The clear definition of grades set forth in the petition for extra virgin, virgin and olive oil do this and allow US consumers to choose a suitable price point to meet their preferences.

Bubbling Over: Is Fermentation More Than a Fad

We asked three fermentation experts if recent popularity of fermented foods is a fading trend or a new food movement. These industry professionals weigh in on their predictions for fermentation’s future. The fermenters include Katherine Harmon Courage (author of “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome”), Aneta Lundquist (owner of 221 BC Kombucha) and Alex Lewin (author of “Real Food Fermentation” and “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond”)

Do you think the surge of fermented food and drinks is a trend will disappear or a new food movement here to stay?

Katherine Harmon Courage, author of “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome”: It’s here to stay. I expect to see it expanding and incorporating into more people’s lives. There is really compelling research with the health benefits, but there’s also these amazing flavors for those of us who weren’t raised with it. Like kimchi. Once you eat kimchi, food seems bland and lacking without it. Koreans describe it as “You need kimchi with every meal.” They can’t imagine eating it without. The flavor and texture experience is a big part of eating. We shouldn’t be forcing it down for our health, but truly enjoying it.

Aneta Lundquist, Owner 221 BC Kombucha: The future is fermented. Stretching back as far as human history itself, the origins of fermentation are hard to track down. People have been teaming up with microbes for much longer than we know. Almost every culture appears to have embraced fermentation for millennia but without a deeper understanding of it’s purpose. Fortunately for us, today’s science became “microbes-curios” and surprised us with some terrific findings. One of the most important ones is that we actually are ONE large thriving ecosystem and its survival is based on an ongoing symbiotic dance between microbial and human cells. Those cells communicate with each other and the outside world, exchange their DNAs and they even shape human behaviors. Now, in the 21st Century, we finally started embracing this profound partnership because of its obvious benefits (gut-brain connection, anti-inflammatory properties, digestive help, depression and Alzheimer aid… this list is almost endless). And there is no way back from here. Demand on fermenting foods is going to only grow from now on. As soon as so called “good microbes” from fermented food find a safe home in human guts, they will call for more of its kind. This is how “they” operate! Suddenly, people will crave kombucha, sauerkraut and kimchi-ferment generally. And that is exactly what we are observing now.

Alex Lewin, author of “Real Food Fermentation” and “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond”: Fermentation is not a new technology — in fact, it is one of our oldest! People have been doing it for millennia, and microbes have been doing it on their own since before humans even darkened the earth.

So by the numbers, it qualifies as a trend or movement.

But it’s definitely not a fad.

And to be fair, in some parts of the world, fermentation was never “out of fashion”. In Korea, for instance, kimchi has been a staple food for a very long time, often eaten with every meal.

My forecast for North America is that fermentation will continue to grow.

This is because fermentation is the meeting point of a few trends that are on the rise here:

– Health. We are more interested in health (and concerned about health) now than we have been at any time in recent memory. We are learning more about gut health and how it affects the rest of human physiology. Fermented foods are directly related to gut health.

– Food. North Americans watch more food TV than ever before, and celebrity chefs are as famous as pro athletes. People are eating things on a regular basis that their parents had never heard of.

– Sustainability/Infrastructure Resilience. Producing and preserving food without reliance on electricity and other infrastructure is an important thing that we as individuals can do to prepare for an uncertain future that will include climate change and may include dramatic societal change and partial or total infrastructure collapse.

- Published in Business