Ask Trevor Wilson how to bake a perfect sourdough boule and Wilson will happily spill his secrets. A rare breed in the realm of professional bakers, Wilson aims to enlighten everyone from hobbyists to master fermenters in the art of creating a great sourdough.

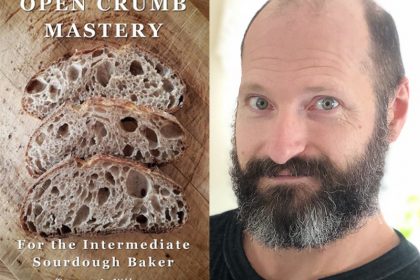

“It’s a fascinating thing. The idea that a simple mixture of flour and water can house a symbiotic culture of wild yeast and bacteria, and that this mixture can be used to leaven bread entirely without the aid of commercial yeast seems astounding to me,” says Wilson, author of the book “Open Crumb Mastery” and the kneading hands behind the blog Breadwerk. His popular Instagram account is full of close-up videos of a knife cutting into a steamy sourdough crust and magazine-worthy images of a gorgeous inner crumb.

“Even after all these years, I still get excited at the thought. There’s just so many possibilities! Every sourdough culture is unique, and therefore the breads made from these cultures are unique as well. I’ve worked with many different starters over the course of my career, and the range of different flavors that can be achieved is simply mind-blowing. Sourdough is more than just a style of bread, it’s a process. A craft. A way of life, really.”

Wilson quit his computer drafting job nearly 20 years ago to bake full-time. He spent 10 years baking at Klingers Bread Company in Vermont, an experience he says was “better education than any baking school could ever provide.” His refreshing philosophy on baking is “that good bread is more than just nutrients and technique — it’s the attention and care you put into it.”

Below, a Q&A with Wilson from his home on the a small island off the coast of Vermont.

How did you first become interested in sourdough baking?

It was actually quite by chance. I was flipping channels on the television when I happened upon a show called “Baking Bread with Father Dominic.” Here was this Benedictine Monk – robes and all – baking bread by hand on public broadcasting. I was drawn in immediately! There was just something so appealing about the simplicity and tradition of it (not to mention the fun of getting your hands deep into the dough). I had to give it a try!

The very first chance I had I decided to make a cinnamon raisin loaf. It was for the family Christmas gathering. I just used the ingredients on hand at my mom’s house – cheap bleached all-purpose flour and a package of long-expired yeast that had been sitting in the pantry for years. As you might imagine, it came out terrible. Dense and underbaked. Like a brick. It didn’t rise at all. Nobody even touched it. But it didn’t matter. I was hooked!

I started baking bread every day – my own recipes because I just have to tinker with things like that – and read everything I could get my hands on. It wasn’t long before I discovered sourdough and sourdough starters. That’s when I truly became obsessed.

Tell me what intrigues you about sourdough.

It’s a fascinating thing. The idea that a simple mixture of flour and water can house a symbiotic culture of wild yeast and bacteria, and that this mixture can be used to leaven bread entirely without the aid of commercial yeast seems astounding to me. Even after all these years, I still get excited at the thought. There’s just so many possibilities! Every sourdough culture is unique, and therefore the breads made from these cultures are unique as well. I’ve worked with many different starters over the course of my career, and the range of different flavors that can be achieved is simply mind-blowing. Sourdough is more than just a style of bread, it’s a process. A craft. A way of life, really.

How did you get your start in artisan bread baking? You’ve worked for multiple artisan bread bakers in Vermont, like Klingers Bread Company and O Bread.

Shortly after I got hooked on bread baking, I decided that this was it – this is how I wanted to spend my life. I was certain of it. Even though I had recently graduated tech school and was ready to start my career as a computer aided drafter – something which I actually really enjoyed – there was no question in my mind that bread baking was my calling. There was just one problem . . . I couldn’t bake a decent loaf for the life of me!

Since I had no clue what I was doing, I figured the first thing I should do is get a clue. I knew I could go back to school and study bread and pastry arts. But I didn’t really care much about pastry at the time, and it seemed rather foolish to pay to learn a skill when I could just get a job at a bakery and get paid to learn that skill instead. So that’s what I did. I applied to every bakery in the area, and I was fortunate that Klingers Bread Company took me in and trained me.

I say I was fortunate because at the time (back in 2000) they were one of the few local bakeries that focused primarily on sourdough breads. And that’s what I was most interested in learning. The ten years I spent with them was better education than any baking school could ever provide. Learning to bake bread at high volume under the constraints of ever-changing production conditions, schedules and demands will teach you so much about the process, the craft, and the business. I wouldn’t trade those days for the world.

Where are you currently working as a baker?

Currently I’m baking at home! But not for production. Primarily it’s for educational purposes (and for fun). My business these days is mainly online. I probably spend more time in front of the computer than at my bench. There are pros and cons to this. It’s nice that I’m able to set my own work schedule and be my own boss (and that I don’t need to wake up at 2 a.m. anymore), but I miss the camaraderie of the bakery and the joys of production baking.

Your blog is full of great insights. I love your philosophy that good bread is more than just nutrients and technique – it’s the attention and care you put into it. Tell me more about that.

I believe that the value of a food is determined by more than just the quality of its ingredients or the recipe with which it is made. There is a subtle and intangible “something” that can be added as well – if the food is made with care and attention, that is. Call it a piece of soul, if you will. This is especially true for something as dynamic and responsive as sourdough. A baker who bakes with heart adds a piece of soul to every loaf. That is the true nourishment of sourdough bread.

Tell me about your book, “Open Crumb Mastery.” It’s a guide for intermediate sourdough bakers.

Well, I wrote it to answer one of the most common questions in bread baking, “How do I get an open crumb?” It seemed to me that most of the answers to this question were either entirely wrong or, at best, severely lacking in nuance. There was actually very little literature on the topic, and what there was usually just glossed over the intricacies of the subject. Simply adding more water to your dough – the answer most commonly given – is terrible advice for newer bakers. They have a hard enough time handling dough as it is, how is making it even wetter and stickier going to help them? What was needed was a book that actually did justice to the topic, and since no one else had written such a book, I figured I might as well do it myself.

I aimed the book at the “intermediate” baker primarily because I didn’t want to waste space covering the same old information that is covered in every other bread book out there. How many times do we need to read the same five day method for creating a sourdough starter? How many times do we need to rehash the same information about ingredients and procedure? The reason all these books covered the same topics over and over again is because they each had to provide information with the beginner in mind. But the problem is that by the time you’ve covered everything the beginner needs to know, you’ve practically run out of space! All that’s left is the recipe section! There’s no room for depth of discussion. Because I self-published my book, I could write whatever I wanted. So I skipped all that and went straight to the good stuff.

You just released your second edition. Tell me what is new in this updated book.

There’s actually quite a bit of new material – almost 100 pages worth (including plenty of new pictures since the first edition was kind of lacking in that department). The main addition to the book comes in the form of a new section dedicated to understanding how the methods discussed in the previous sections relate to other loaf qualities such as shape, height, and volume. There is more to a loaf than just its crumb. The original edition just lightly touched upon these topics; the new edition gives them their due. Along with some other additions (such as a discussion of whole grain, and a couple new crumb analyses focusing on retarding bulk fermentation), the new material provides a more complete picture regarding how the variables of technique and method affect the entirety of the final product.

Describe the open crumb technique.

That’s a tough one. It’s such a deep discussion that I could never do it justice in an interview alone. That’s why I wrote a book! My main point is that open crumb is primarily a matter of fermentation and dough handling. Hydration, while important, is only a distant third.

You said “Open crumb is 80% fermentation and handling.” Tell me more about that.

It seems to me that much in life follows the Pareto Principle – that 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. Bread baking is no exception. When it comes to achieving an open crumb, fermentation and dough handling will provide you with 80% of the effect. Therefore, it seems prudent to me that a baker interested in open crumb should spend the bulk of their time learning the skills of fermentation and handling. That will provide the highest return on time invested.

And make no mistake, these are skills. Skill takes time to develop. Practice is paramount. Only through experience will a baker learn to master fermentation and dough handling. But it’s a necessary and vital part of the craft. There’s really no way around it. For any baker that’s seeking to achieve an open crumb, they must start with fermentation and dough handling.

What makes a fermented sourdough unique from other breads?

It’s all about that sourdough culture! The starter is the heart and soul of it all. It provides qualities to bread that commercial baker’s yeast simply can’t replicate. Now whether that’s for better or worse is a matter of opinion. Not every style of bread benefits from the use of sourdough. There’s a large world of bread out there, and yeast breads certainly have their place.

But sourdough has its place as well. And judging by the growing interest, its place seems to be expanding day by day. For good reason, I think. Sourdough possesses a combination of crust, crumb and flavor that is difficult – if not near impossible – to achieve with baker’s yeast alone. Especially flavor. It’s just so much more complex than yeast bread. Deeper. More interesting. Intriguing, even. The acids and other flavor and aroma compounds generated by a sourdough starter are what make sourdough breads truly stand out. Comparable crust and crumb might be had with yeast breads that are long-fermented and skillfully made, but the flavor of sourdough can’t be copied and can’t be faked. Only the real thing will do.

How do you ferment your sourdough?

Many different ways. As I often say, the method makes the bread. How you choose to ferment your dough will have a huge impact on the bread’s flavor, as well as many other qualities of the final loaf. Different methods of managing fermentation will therefore result in different breads. So the manner in which you choose to ferment a dough is dependent upon what kind of bread you are making, and what qualities you are seeking in a loaf. When you include other variables such as folding methods/schedules, shaping techniques, starter maintenance routine, etc. then the possibilities really are endless. It’s up to each baker to ferment and handle their dough in a way that works best for them and their needs.

Tell me about the sourdough starter you use.

That’s a tricky question, because I use many different starters. In fact, you can say I have a bit of an addiction. I love trying out new starters – and I have a fridge full of them! Some are better suited for certain flavors or styles of bread than others, but still, I often bring different starters into rotation based on nothing more than whim. I just like playing around with them. Many I’ve created myself, but quite a few I’ve purchased as well.

I’d say my favorite starter (you could call it my main starter since I use it more often than any of the others) is an “Alaskan” starter that I got from the last place I worked. They had purchased it online but hadn’t had any success in getting it active. I took it home and brought it to life, and I knew it was a keeper from the first test loaf I ever made with it. It practically brought tears to my eyes. The flavor was so close to the old Pioneer Sourdough I’d grown up eating in Southern California that I simply couldn’t believe it. It was a flavor I’d been searching for — and had yet to find — since I first started baking sourdough. That old bakery closed a long time ago and so I thought I might never experience that taste again. It’s a bit of a fickle starter, and I don’t always get that perfect flavor from it, but when I do it’s a glorious thing.

More and more retail news show sales of sourdough bread are increasing. Why do you think more people are buying sourdough bread?

Over the last 35 years or so, there’s been a strong “push” by bakers themselves to bring awareness to this style of bread. The old methods of sourdough baking had practically gone extinct in many parts of the world (though they were still thriving in others). This was especially true in the United States, where factory-made sandwich bread had almost completely taken over the market. For many, sourdough was something either long forgotten or completely unknown. For those bakers back in the day who were making bread the old way, it was quite the struggle to find customers.

Fortunately, over the years they – and those who followed – have managed to bring awareness to the pleasures and benefits of sourdough bread. It wasn’t always an easy sell. But through education and promotion, sourdough is now part of the scene and here to stay. You might even say it’s become rather trendy. The reasons are many: nutrition and health, flavor, crust, crumb, history and tradition, etc. It seems to me that artisan sourdough bread is the food fashion of the moment, but then, I might be a bit biased here.

Do you think consumers awareness of fermented foods is increasing?

Awareness of fermented foods is definitely increasing. Quite drastically, I might add. It seems that fermented foods are everywhere nowadays, with more and more popping up on the shelf every day. And that’s a good thing as far as I’m concerned. The more that folks are exposed to these foods, the more they will be enjoyed — and eventually adopted as a natural part of the cuisine. That brings more interest, more variety, and more flavor to the food scene.

What challenges do fermented food producers face?

There are many challenges faced by the current crop of fermented food producers, and different industries face different challenges. Probably one of the bigger challenges that crosses over many categories of fermented foods is simply getting consumers – many of whom have had little exposure to these types of foods – to open their minds and give fermented foods a try. This is especially true for producers that market raw ferments with live cultures. Most of us have grown up in a world of pasteurization and sterilization. The idea of a raw fermented product – though perfectly natural throughout most of history – may seem unnatural to those who have no history with it. Needless to say, educating the market will be an ongoing challenge.

Another major challenge these days is simply the matter of competition. With more and more producers jumping onto the fermented foods bandwagon, competition keeps growing and growing. Of course, this is regional and market based. So long as the market keeps growing, then there is more room for additional producers. But in places where the market has slowed, or that are already oversaturated with producers, expanding competition will cut into already slim profit margins.

I see this all the time in the baking industry. New artisan bakeries are constantly opening up on a daily basis. Many are (similarly) making a trendy style of dark, crusty, high-hydration bread. So it’s becoming more and more difficult for these bakeries to distinguish their product from all the rest (at least in the saturated urban areas). Baking is a hard business with slim margins, and it is made harder all the more when you have a bakery selling the same kind of bread on every corner. I fear that many of these bakers – even those who bake outstanding bread – will be forced to close shop in the not-too-distant future.

What are the fermented food industry strengths?

Its biggest strength is its growing popularity. As more and more folks are exposed to the wonderful variety and flavors of fermented foods, and as more become aware of their health and nutrition benefits, the good word will continue to spread. The market is growing rapidly, and will likely continue to do so for quite some time. Producers of fermented foods are well-positioned to grow their businesses as the industry continues to expand and evolve.

Where do you see the future of the fermented food industry?

It’s hard to say. I’ve spent an entire career in just one small segment of the industry. With “nose to the bench,” so to speak, I’ve had a rather limited view of the fermented food industry as a whole. I’m no trend forecaster. It seems to me that authors such as Michael Pollan, Sally Fallon, and Sandor Katz (to name a few) were instrumental in bringing us to this place of awareness and appreciation for wholesome and traditional foods that we now find ourselves in today. Who’ll step up next and where do we go from here? That’s the million-dollar question.

What’s your advice to other entrepreneurs starting a fermentation brand?

Know your product, know your market, know your margins.

The first one is usually the easiest – most of the folks that are jumping into the fermented food business are doing so precisely because they are so passionate about their product. No need to elaborate this point.

The second is vital to those who actually wish to sell a product. Who is your target customer? Where are they? Why should they buy from you? Are you selling wholesale or retail? Or both? Are you selling at farmer’s markets? Whole foods markets? Supermarkets? Are you selling to restaurants, delis, or other food preparation establishments? Are you selling online? In catalogs? At local farm stands? Who’s your competition? Where do they sell? How does your product differ from theirs? Why should a customer purchase your product instead of theirs? What is your value proposition?

When you have answers to these questions (and many more) then you can begin to understand your market. Understanding your market helps you to understand how best to sell to it. Often times in the food business (particularly in craft foods), customers don’t just want to buy a product to eat. They’re looking for a higher value. Can you sell them that higher value? Can you sell them history and tradition? Can you sell them nutrition and health? Can you sell them a story, or a feeling, or an idea? Can you sell them a way of thinking? A way of life? A community? The business that can sell these things is the business that succeeds.

The third point speaks to the bottom line. So many new entrepreneurs jump into the food business out of passion and idealism, but they forget the business part in “food business.” It is a business, and don’t forget it. If you can’t turn a profit or manage cashflow, then you won’t be in business very long. From an operations standpoint, efficient production is profitable production. So focus on efficiency.

Inefficient production includes things like making too many different products in order to appeal to every taste instead of focusing on and maximizing the big sellers (Pareto Principle again), using wildly different production methods for different products when you could combine and/or streamline the processes instead (i.e. completely different recipes for different products instead of using just one or two base recipes that can then have specialty ingredients simply added to them in order to create different products), and poorly designed production environments that don’t allow for economy of motion (if you’re running around all over the place like a chicken with its head cut off then you may need to improve your floor layout). Those are just a few examples of inefficient production.

Be especially careful how you grow and never lose sight of your margins. Many new business owners are too quick to accept large accounts in an effort to expand their business – especially if they’re struggling. But far too often they come to regret that decision, particularly smaller craft producers. Large operations are built to benefit from economies of scale, but small local producers often struggle due to limitations in batch size, work space, and available labor. So accepting large accounts results in more batches which results in more labor. As labor costs go up, profit margins go down. The end result is a lot more work for just a little bit more money. Quality tends to go down, capacity gets maxed out for little added profit, and cashflow gets tied up in additional inventory. Now you’re stuck, unable to pay bills, and unable to take on new or more profitable accounts. Avoid that situation like the plague.

It’s pretty simple really; a dollar saved is a dollar kept whereas a dollar earned is but a dime kept. That’s margin. Efficiency saves you dollars. Responsible cost cutting saves you dollars (so long as it doesn’t come at the cost of quality or efficiency). And intelligent growth saves you dollars. If you can produce efficiently, earn a profit, and effectively manage growth and cash flow, then you’ll do just fine.