The World of Fermented Foods

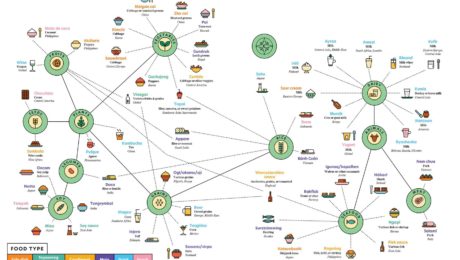

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Does Geography Matter for Sourdough Flavor?

Results of the first large-scale study of sourdough starters were released last week — and the conclusions are fascinating, challenging myths about sourdough. Scientists from four different universities studied 500 sourdough starters from four continents, with an aim to determine microbial diversity.

“We didn’t just look at which microbes were growing in each starter,” says Erin McKenney, co-author of the paper and an assistant professor of applied ecology at North Carolina State University. “We looked at what those microbes are doing, and how those microbes coexist with each other.”

The most striking finding: geography doesn’t matter.

Sourdough enthusiasts preach that location and climate will alter sourdough flavor. San Francisco has long held bragging rights for the most distinctive taste profile. But, of the 500 samples, there was little evidence of geographic patterns.

“This is the first map of what the microbial diversity of sourdoughs looks like at this scale, spanning multiple continents,” says Elizabeth Landis, co-lead author of the study and a PhD student at Tufts. “And we found that where the baker lives was not an important factor in the microbiology of sourdough starters.”

Alex Corsini, CEO and founder of sourdough pizza brand Alex’s Awesome Sourdough (and TFA advisory board member), says the research “demystifies the misconception that sourdough is only good in certain pockets of the world such as San Francisco.” Great sourdough, he says, is about the raw materials.

“It further shows why sourdough is ubiquitous all over the world — starters can thrive anywhere as nature provides the magic and bakers just need to be in a position to coax out a result without ruining the magic — the magic here being the microbial balance needed to ferment and levain baked goods,” Corsini says.

The research also found there is no one single variable responsible for sourdough variations, bucking conventional baking wisdom.

“What we found instead was that lots of variables had small effects that, when added together, could make a big difference,” says Angela Oliverio, co-lead author of the study and a former PhD student at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “We’re talking about things like how old the sourdough starter is, how often it’s fed, where people store it in their homes, and so on.”

As a commercial sourdough producer, Corsini values the “low and slow” process to master a sourdough batch, especially when making it consistently on a large scale. Alex’s Awesome Sourdough undergoes a 70-hour ferment using high-quality flour, filtered water and a decades-old starter.

“Although location makes little or no impact on the starters microbial ecosystem, regulating temperature and time is fundamental and adjustments need to be made based on the location you are in (hot climate, cold climate, humidity, etc.) to get a desired result,” Corsini says. “We make slight adjustments throughout the year to ensure a consistent texture and flavor in our dough.”

The study found variations in dough rise rates and aromas were due to acetic acid bacteria, “a mostly overlooked group of sourdough microbes.” The bacteria slowed the rise time and gave the sourdough a vinegary smell. Researchers were “surprised” that 29.4% of the samples contained acetic acid bacteria.

“The sourdough research literature has focused almost exclusively on yeast and lactic acid bacteria,” says Ben Wolfe, co-author of the study, associate professor of biology at Tufts University (and also a TFA advisory board member). “Even the most recent research in the field hadn’t mentioned acetic acid bacteria at all. We thought they might be there to some extent, since bakers often talk about acetic acid, but we were not expecting anything like the numbers we found.”

The 500 sourdough starters studied mostly came from home bakers in the U.S. and Europe. Researchers performed DNA sequencing for each sample, narrowing down to 40 starters as being representative of the diversity of the original array.

Those 40 were: assessed by sensory professionals for aroma profile, chemically analyzed to determine the organic compounds released by each and then measured for dough rise time.

“I think it’s also important to stress that this study is observational — so it can allow us to identify relationships, but doesn’t necessarily prove that specific microbes are responsible for creating specific characteristics,” says Wolfe. “A lot of follow-up work needs to be done to figure out, experimentally, the role that each of these microbial species and environmental variables plays in shaping sourdough characteristics.”

“And while bakers will find this interesting, we think the work is also of interest to microbiologists,” Landis adds. “Sourdough is an excellent model system for studying the interactions between microbes that shape the overall structure of the microbiome. By studying interactions between microbes in the sourdough microbiome that lead to cooperation and competition, we can better understand the interactions that occur between microbes more generally — and in more complex ecosystems.”

The research, “The Diversity and Function of Sourdough Starter Microbiomes,” was done with support from a National Science Foundation grant.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

The Science Behind Sourdough

Sourdough has become the darling of the pandemic pantry, as people experiment with a starter of microbes in their home kitchen. Scientists are just beginning to “discover that the microbes in a sourdough depend not just on the native microbial flora of the baker’s house and hands, but also on other factors like the choice of flour, the temperature of the kitchen, and when and how often the starter is fed,” according to an article in Scientific American. The magazine interviewed multiple microbiologists on the science behind a great sourdough loaf.

“When we study sourdough science, we learn that we know remarkably little for a technology that’s — what? — 12,000 years old,” says Anne Madden, a microbiologist at North Carolina State University.

Read more (Scientific American)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Stopping “Sourfaux” in the UK

Artisan bread bakers in the UK are banding together for Sourdough September, pushing for new government legislation to stop the rise of “sourfaux” bread. Laws in the UK allow retailers to sell unwrapped bread loaves without displaying an ingredient list.

Writes the Real Bread Campaign organizer Chris Young: “In the hands of skilled Real Bread bakers, this longer, slower fermentation, allows lactic acid bacteria in the starter to cause changes in the dough that result in bread with a glossy crust and crumb, and a greater complexity of flavour and aroma.”

The UK government promised in 2018 to protect consumers from buying products erroneously label led as “sourdough.” But no action has been made. More than 50 UK bread bakeries have launched their own labeling promise, signing The Sourdough Loaf Mark scheme last month, urging all bread makers to display a full ingredient list.

Read more (Food Navigator)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Sour Sells

American’s flavor choice of 2020: the funkier, the better. Fermentation reigns as sour becomes a selling point. A new article in Yahoo Life highlights fermented food and drink ancient roots and modern revival. A naturopathic doctor, kombucha brand leader, food influencer, wine shop owner and chef/owner of two Korean restaurants share their thoughts on why people love the “interesting and complicated” flavors of fermented food. Fermentation delivers on gut health benefits, is made with clean, unprocessed ingredients, preserves seasonal ingredients and “tells a story.”

The article continues: “They’re nuanced, many-layered. Kimchi and sourdough alike smack of acid and sour-sweet brine, even for those of us with less-than-refined palates. They taste like the process of aging. And while the wellness revolution would have us believe that fermented food’s uptick in popularity is merely a product of the fact that we’re eternally prepared to flirt with anything that just might make us feel better, the phenomenon cuts deeper than that. There’s something to be said for flavor that comes with a narrative — that tastes of its own timeline.”

Read more (Yahoo Life)

- Published in Food & Flavor

“Backslop Romance” — Inoculation, Not Contamination

By: Marina Jade Phillips, Trellis & Co.

The first two months of 2018 marked both my first trip to Mexico and my first bicycle tour. Living on two wheels did not slow my fermentation habit; I toted stainless steel jars of fermented vegetables in my panniers. I credit consuming lacto-bacteria with my lack of stomach troubles that can plague travelers in South America. Regularly introducing healthy bacteria into our digestive tract is a great way of inoculating our body with microbes that are on our team. The amount of attention probiotics have received in recent years is long overdue. Traditional cultures have known about the delicious and health-promoting qualities of fermented foods for hundreds of years, even before it was scientifically proven.

Backslop is Such Beautiful Word

Contamination and inoculation are two sides of the same food processing coin: the impact of a small quantity of the right or wrong material can be drastic. The former is the stuff of nightmares for food companies forced to recall tainted products, and suffering travelers perched atop or hunched over a toilet. The latter is how fermented flavors have been passed down through time, sometimes across generations, from one bottle, crock, or barrel to the next. Inoculation is so ubiquitous to the craft that traditional sausage makers gave it a name: backslop.

Backslop, unsavory as it may sound, simply refers to the practice of saving a bit of the last successful batch and incorporating it into the new one, ensuring a small number of the micro-organisms that populated the previous batch will go forth and multiply. There are several reasons why this technique is valuable to both professionals and home cooks. Foremost, the time required for complete fermentation decreases dramatically. A new jar of sliced cabbage or jug of fresh squeezed fruit juice is teeming with all kinds of bacteria and yeast, some of which will produce the desired results, and some of which will produce something inedible.

By introducing a healthy colony early in the process, desirable microbes get a head start and usually out compete less desirable ones in the race to inhabit a new environment. If those microbes have a particularly unique characteristic (champagne yeast produces more carbon dioxide than other wine yeasts, for instance), that character can be reproduced, sometimes leading to outstanding strains by which certain makers and regions become famous.

A 5-Year Love Affair

In more humble corners of the globe, far from French vineyards, I once had a relationship with a sourdough starter that lasted five years.

A sourdough culture becomes more complex with age, and as time went by she (yes, she—around her first birthday I named her Henrietta) developed her own unique flavor. One morning, I came into my kitchen and saw Henrietta’s container on the floor, licked almost all the way clean. A dog had gotten up on the counter, somehow removed the lid, and all but devoured my precious bread making ally. I scraped the dried crust of starter that remained from the edges of the bowl and rehydrated it with water.

Over the next few days I added a bit more flour and water at regular intervals, and in less than a week my robust friend was back in action. I could have sighed, cursed dogs under my breath, and made a new starter, but I was attached to Henrietta, and thrilled to revive her with such little material.

The beginning fermenter has a few options for ensuring success. Of course, there is always the option of simply hoping for the best. Usually, if the food to be fermented is fresh and healthy and the containers and hands in contact with it are clean, odds are in our favor that the microbes that make things sour and bubbly are going to win. However, a splash of the liquid floating around the top of high-quality yogurt (look for something with “active cultures”) will introduce a bit of the right bacteria and speed the process along. A small slosh of juice from a thoroughly fermented sauerkraut or brined vegetable jar will help get the next one going.

Those interested in experimenting with fermented dough will be delighted to know that a sourdough starter is incredibly easy to make: stir equal parts flour and water every day until it smells sour. Wild yeast lands on top of the mixture and is incorporated with every stirring.

Aid this process by dropping an unwashed and unsprayed berry (grapes work best) into the mixture for a couple of days (retrieve the berry before it starts breaking down). Yeast which covers the skins of all fruits will slough off and populate the latent starter. To keep this culture thriving, the sourdough baker saves a small amount of the starter and adds to it more flour and water. Starters exist that are rumored to be hundreds of years old, passed down in just this way.

Practice Safe Fermenting

Interestingly, foods that are not fermented are more prone to contamination from bacteria that can make us very ill, and in the worst cases, kill us. The culprits in large and small-scale food poisonings are often raw and unfermented vegetables. By fostering beneficial bacteria in a salty and acidic environment, we can safely enjoy raw vegetables with all their fiber and nutrient content without the risk of ingesting pathogens.

About Trellis & Co.: We started as a family business created by a bioengineer living on a homestead in one of the remotest areas in the Lower 48. When “running to the store” is a 4-hour drive, every purchase must be a robust and functional investment. Here at Trellis + Co. we design products worth investing in.

Our lifestyle inspired our line of garden-to-table kitchen tools. As gardeners, cooks, and canners, we develop creative solutions to our own kitchen conundrums and pass on that wisdom to you. Also, since we’re kind of obsessed with the planet, our products are designed to last a lifetime — keeping money in your pocket and garbage out of landfills.

- Published in Food & Flavor

The Science of Yeast, the Microbe in your Pandemic Bread

Humans have been baking fermented breads for at least 10,000 years, but commercial yeast and flour companies have never seen demand so high. National Geographic shares “a story for quarantined times, about extremely tiny organisms that do some of their best work by burping into uncooked dough.”

Scientists describe the microbes behind the work fermenting the bread. “It’s this wonderful living thing you’re working with,” says Anne Madden, a North Carolina State University adjunct biologist who studies microbes. She and partner scientists showed recently that when bakers in different locales use exactly the same ingredients for both starter and bread, their loaves come out smelling and tasting different. “Which I think is fantastic,” she says. “It’s evidence of the unseen. And as a microbiologist, you so rarely get to measure things about microbes with your nose and your taste buds.”

Read more (National Geographic)

- Published in Science

Sourdough Library Catalogues Hundreds of “Mothers”

The man behind the world’s only sourdough library shares how he maintains a collection of 125 sourdough mothers from all over the world. The mothers are stored in Mason jars in a chilled cabinet. Library founder Karl De Smedt cares for them in France, refreshing the jars every two months with back stocks of the original flours used (and contributed) by the providers. De Smedt travels the world for new mothers, prioritizing “renown, unusual origins, the type of flour used, and the starter’s approximate age.” He adds up to two dozen new sourdoughs each year, ranging from cooking schools, home-bakers, pizzerias, artisan and industrial bakers.

“Most importantly, the sourdough must come from a spontaneous fermentation, and not inoculated with a commercial starter culture,” De Smedt says. “Sourdough is the soul of many bakeries. When bakers entrust you with their souls, you’d better take care of it.”

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Science

How Can Artisan Bakers Scale Up Without Hurting Fermentation Process?

Open crumb and flavor depth are hallmarks of a fermented, artisan bread. But as artisan bakers scale up production, “fermentation has been the ultimate challenge,” according to Baking Business. “It is critical to a craft bread’s profile, and bakers are often unwilling to compromise on this step.” Making extra dough can decrease the fermentation process if not handled properly. Baking Business, the baking industry e-zine, explores how artisan bread bakers are using automated fermentation to transport mixing bowls, proof and oven load, without losing the artisan style.

Read more (Baking Business)

- Published in Business

More People Isolation Bake

Wired writes about the “Stay at Home Bread Boom,” which is causing flour and yeast to sell out on grocery store shelves. More people are baking at home during the coronavirus outbreak, some to start a new hobby and others out of necessity because bread is also selling out. Stephen Jones, a wheat breeder and the director of Washington State University’s Bread Lab, recommends people start with sourdough because it doesn’t require yeast. “You can start a sourdough culture in just a couple days. I mean, you just basically mix flour and water and let it sit there, and the bacteria and yeast will come to it. So that’s a nice experiment.”

Jones also encourages people not to get discouraged by the perfect “Instagram bread load.” He explains: “Well it’s open crumb, so it’s — it’s called the Hairy Forearm Crumb Shot. It’s somebody holding up a rustic loaf that’s been cut in half and has these huge bubbles in it and things like that. People think if they can’t do that, they’re failing at baking. It’s part of this notion that your bread has to look perfect to be good, right? People should take pressure off themselves in that way.”

“It doesn’t surprise me in this environment that people are baking, because they need to and they want to. But I think an important part too is how little time it takes to bake a loaf of bread. Not totally, but in terms of the work that’s required when you’re actually working on the bread, that can be about 20 minutes. Even if you’re doing a long ferment, and it goes for a full day and then you bake it … including prep and folding and cleanup, you’re talking about 20 minutes out of your day. The rest of the time is waiting.”

Read more (Wired magazine)

- Published in Health