The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

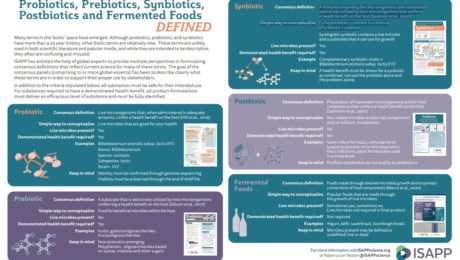

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

How a Water Kefir Producer Tanked

Scott Whitley, of failed LAB Water Kefir, shares lessons learned from launching – and then shuttering — the business. Whitley is open about his blunders, providing great insights for fermentation brands.

His first problem: Knowing nothing about the food and beverage industry, and even less about selling a fermented drink. The company used a recipe that contained fermentation blunders, so products exploded on store shelves!

Second problem: Spending too much time on low-leverage activities. The two co-founders were filling tens of thousands of bottles of water kefir themselves — something Whitley says in hindsight “was a big mistake.” They thought they were saving money but, in reality, they weren’t making enough money to stay afloat. Bottles sold for $5.50 at retail, and stores bought them for $3.30. After covering production costs, LAB Water Kefir made only $1.10 per bottle. They were bringing in a few thousand dollars per month, but expenses were over $6,500.

Third problem: Lack of consumer understanding. The brand sold well at farmers markets, where half the people who approached their stand and sampled the drink would buy a bottle. But they learned that many people didn’t know what water kefir was. Whitley shares the story of watching a man grab a bottle off the shelf, shake it, then open it to drink – and the water kefir shot out of the bottle and all over his face. Also, people don’t go to a grocery store to experiment with a new, pricey drink, so their water kefir didn’t sell well at retail.

Read more about the story behind the brand at Trends.

Read more (Trends)

- Published in Business

Ireland’s Fermented Drinks Under Scrutiny

After a study found 91% of plant-based, fermented drinks in Ireland make unauthorized health claims, the Food Safety Authority of Ireland (FSAI) has published a guide on how to produce such beverages safely and label them accurately.

The FSAI examined 32 unpasteurized drinks currently sold on the Irish market – including kombucha, kefir and ginger soda – and found that most did not comply with EU and Irish food labelling and health regulations. The study found 13% had alcohol levels above labelling thresholds, and 75% lacked required label information, like the address of the producer and “best-before” date.

“The methods used in producing unpasteurized fermented plant-based products can be difficult to manage,” notes Dr. Pamela Byrne, FSAI chief executive. “The guidance will help producers to achieve consistent production methods, safe storage, safe handling and safe transportation of fermented beverages.”

Read more (Agriland)

Fermentation vs. Fiber — Both Help, but Fermentation Shines

A diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response, according to researchers at Stanford University’s School of Medicine.The groundbreaking results were published in the journal Cell.

In the clinical trial, healthy individuals were fed for 10 weeks, a diet either high in fermented foods and beverages or high in fiber. The fermented diet — which included yogurt, kefir, cottage cheese, kimchi, kombucha, fermented veggies and fermented veggie broth — led to an increase in overall microbial diversity, with stronger effects from larger servings.

“This is a stunning finding,” says Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford. “It provides one of the first examples of how a simple change in diet can reproducibly remodel the microbiota across a cohort of healthy adults.”

Researchers were particularly pleased to see participants in the fermented foods diet showed less activation in four types of immune cells. There was a decrease in the levels of 19 inflammatory proteins, including interleukin 6, which is linked to rheumatoid arthritis, Type 2 diabetes and chronic stress.

“Microbiota-targeted diets can change immune status, providing a promising avenue for decreasing inflammation in healthy adults,” says Christopher Gardner, PhD, the Rehnborg Farquhar Professor and director of nutrition studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center. “This finding was consistent across all participants in the study who were assigned to the higher fermented food group.”

Microbiota Stability vs. Diversity

Continues a press release from Stanford Medicine News Center: By contrast, none of the 19 inflammatory proteins decreased in participants assigned to a high-fiber diet rich in legumes, seeds, whole grains, nuts, vegetables and fruits. On average, the diversity of their gut microbes also remained stable.

“We expected high fiber to have a more universally beneficial effect and increase microbiota diversity,” said Erica Sonnenburg, PhD, a senior research scientist at Stanford in basic life sciences, microbiology and immunology. “The data suggest that increased fiber intake alone over a short time period is insufficient to increase microbiota diversity.”

Justin and Erica Sonnenburg and Christopher Gardner are co-authors of the study. The lead authors are Hannah Wastyk, a PhD student in bioengineering, and former postdoctoral scholar Gabriela Fragiadakis, PhD, now an assistant professor of medicine at UC-San Francisco.

A wide body of evidence has demonstrated that diet shapes the gut microbiome which, in turn, can affect the immune system and overall health. According to Gardner, low microbiome diversity has been linked to obesity and diabetes.

“We wanted to conduct a proof-of-concept study that could test whether microbiota-targeted food could be an avenue for combatting the overwhelming rise in chronic inflammatory diseases,” Gardner said.

The researchers focused on fiber and fermented foods due to previous reports of their potential health benefits. High-fiber diets have been associated with lower rates of mortality. Fermented foods are thought to help with weight maintenance and may decrease the risk of diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease.

The researchers analyzed blood and stool samples collected during a three-week pre-trial period, the 10 weeks of the diet, and a four-week period after the diet when the participants ate as they chose.

The findings paint a nuanced picture of the influence of diet on gut microbes and immune status. Those who increased their consumption of fermented foods showed effects consistent with prior research showing that short-term changes in diet can rapidly alter the gut microbiome. The limited changes in the microbiome for the high-fiber group dovetailed with previous reports of the resilience of the human microbiome over short time periods.

Designing a suite of dietary and microbial strategies

The results also showed that greater fiber intake led to more carbohydrates in stool samples, pointing to incomplete fiber degradation by gut microbes. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that the microbiome of a person living in the industrialized world is depleted of fiber-degrading microbes.

“It is possible that a longer intervention would have allowed for the microbiota to adequately adapt to the increase in fiber consumption,” Erica Sonnenburg said. “Alternatively, the deliberate introduction of fiber-consuming microbes may be required to increase the microbiota’s capacity to break down the carbohydrates.”

In addition to exploring these possibilities, the researchers plan to conduct studies in mice to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which diets alter the microbiome and reduce inflammatory proteins. They also aim to test whether high-fiber and fermented foods synergize to influence the microbiome and immune system of humans. Another goal is to examine whether the consumption of fermented foods decreases inflammation or improves other health markers in patients with immunological and metabolic diseases, in pregnant women, or in older individuals.

“There are many more ways to target the microbiome with food and supplements, and we hope to continue to investigate how different diets, probiotics and prebiotics impact the microbiome and health in different groups,” Justin Sonnenburg said.

Other Stanford co-authors are Dalia Perelman, health educator; former graduate students Dylan Dahan, PhD, and Carlos Gonzalez, PhD; graduate student Bryan Merrill; former research assistant Madeline Topf; postdoctoral scholars William Van Treuren, PhD, and Shuo Han, PhD; Jennifer Robinson, PhD, administrative director of the Community Health and Prevention Research Master’s Program and program manager of the Nutrition Studies Group; and Joshua Elias, PhD.

Researchers from the nonprofit research center Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub also contributed to the study. Here’s the complete press release from Stanford Medicine News Center.

Kefir Brands Respond

The kefir brands recently tested for their probiotic claims are challenging the results.

In May, a study found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic counts and “contained species not included on the label.” The Journal of Dairy Science Communications published the peer-reviewed work by researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University.

“Based on the results…there should be more regulatory oversight on label accuracy for commercial kefir products to reduce the number of claims that can be misleading to consumers,” reads the study. “Classification as a ‘cultured milk product’ by the FDA requires disclosure of added microorganisms, yet regulation of ingredient quality and viability need to be better scrutinized. All 5 kefir products guaranteed specific bacterial species used in fermentation, yet no product matched its labeling completely.”

Researchers tested two bottles of each of five major kefir brands: Maple Hill Plain Kefir, Siggi’s Plain Filmjölk, Redwood Hill Farm Plain Goat Milk Kefir, CoYo Kefir and Lifeway Original Kefir. Bottles were measured for microbial count and taxonomy to validate label claims.

The Fermentation Association reached out to the five brands involved and asked for their responses to the results. Redwood Hill and Lifeway both submitted detailed statements. Maple Hill, Siggi’s and CoYo did not return multiple requests for comment.

Probiotic Count

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs), and the study found kefir from both Lifeway and Redwood Hill contained fewer CFUs than what was claimed on the label. But these brands — who send their products to third-party labs for testing — said the results are not accurate.

Lifeway refutes the assertion that their Original Kefir did not meet the claimed probiotic count. Lifeway references U.S. Food and Drug Administration food labeling laws, which dictate that a product “must provide all nutrient and food component quantities in relation to a serving size.” Lifeway’s label on their 32-ounce bottle says that the serving size of kefir is 1 cup, making the claim of 25-30 billion CFUs per serving size accurate.

The study results, Lifeway notes in their statement, were “premised upon an erroneous assumption that Lifeway claims it has 25-30 billion CFUs per gram” rather than per serving size.

“The authors’ flawed assumption is perhaps a result of their lack of familiarity with FDA labeling requirements or a result of merely overlooking the details in order to support their intended conclusions going into the testing,” reads a statement from Lifeway.

In fact, Lifeway points out, the study’s “erroneous conclusion premised upon the flawed assumption…actually proves the accuracy of Lifeway’s claim of 25-30 billion CFUs per (8 ounce) serving.”

Redwood Hill Farm, too, refutes the study’s conclusion. Their Goat Milk Kefir currently includes the phrase “millions of probiotics per sip” on its label. The label referenced in the study was an old version that claimed “hundreds of billions” of probiotics, which was discontinued last year. According to Redwood Hill Farm, that old label was based on third-party testing that confirmed hundreds of billions of CFUs per 8-ounce serving. But careful review of the kefir’s probiotic counts in 2019-2020 found some CFUs in the hundreds of billions and others in the tens of billions. Redwood Hill changed their label to millions rather than billions “to be absolutely sure that we could meet our target claim on a consistent basis.”

Variation in CFU counts is common in traditional plating testing techniques. Redwood Hill referenced a study published in Nutritional Outlook that found that plating results can vary 30-50%.

“Given the challenges around probiotic CFU enumeration, we were not too surprised to see a discrepancy between the number of CFUs in our Goat Milk Kefir found in the study and our past analyses,” reads the statement from Redwood Hill Farm. “Like all living organisms, probiotics are challenging to control and measure. A particular microorganism’s ability to reproduce is impacted by a variety of factors, including temperature, oxygen level, variations in the nutrient composition of the milk, and pH level. Our kefir has a sixty-day shelf life and during that time the different types of bacteria in the product will peak and die-off in relation to the conditions those particular bacteria like. For example, fermented dairy products naturally become more acidic (lower pH) as they age and while some bacteria thrive in acidic environments, others’ reproduction is stunted. This makes the exact CFU count rather volatile not only from bottle to bottle, but also throughout the timespan between when that bottle leaves our facility and when it expires.”

Redwood Hill Farm’s most recent testing measured 400 million CFUs per gram or 96 billion per serving (1 cup). These figures compare with what the study found — 193 million CFUs per gram or 46 billion per serving.

“Although the University of Illinois study found only half the probiotic cells that our study did, this is actually not that wide of a variation in bacteria reproduction based on all of the conditional factors outlined above,” their statement reads.

Species Count

The study’s test results found all kefir brands contained species not on the label. Lifeway notes their culture claims are based on the time of manufacture, not on expiration date. “Moreover, the authors validate that all of the claimed culture species except for the bifidos, Leuconostoc and L. reuteri, (which could be at a low concentration due to time of shelf-life), were identified in their testing,” reads Lifeway’s statement.

Redwood Hill Farm says that, based on the study results (that “2 Lactobacillus delbrueckii subspecies or 3 Lc. lactis subspecies could not be identified” in their kefir), they are pursuing further analysis. They’ve contacted their culture supplier for further insight, and are sending new samples to a third-party lab.

“These cultures are at the heart of the product and are what transforms the goat milk into a yogurt drink with its characteristic thick and creamy texture and tart flavor,” reads the Redwood Hill Farm statement. “It’s difficult to understand how these core active agents in the kefir could not be present in the product at any stage in its lifecycle.”

DNA vs. Plating Methodology

The study utilized both DNA sequencing and traditional plating methodologies, even though plating testing alone is considered the industry standard for kefir. Plating testing for kefir is done in a microbiology laboratory where it’s incubated to determine bacteria colony growth.

The study itself notes: “Limitation of DNA-based sequencing methods could explain why taxa stated on labels were not detected and why unclaimed viable species were identified.”

Lifeway points out: “This concession as to testing limitations is critical to note as it is but one explanation of many as to why various species may have not been detected. First and foremost, the authors fail to validate the DNA extraction method to establish that it delivers all the available DNA in the type of dairy product analyzed; for example, they do not appear to have broken down the calcium bonds. Further, they appear to not have undertaken the required extra enzymatic treatments. Moreover, for their microanalysis, they are using MRS [a method for cultivation of lactobacilli] but only incubating for 48 hours. As most kefir products would contain a significant amount of Lactococci, there is a high chance of not detecting this species unless you go to 72 hours of incubation. Another unknown important factor in the testing is the time period within the cycle of the shelf-life of the product that was tested. This is critical as the longer the product sits on a shelf, the fewer number of live and active bacteria will be present.”

Meanwhile, Redwood Hill Farm says “our team will continue to educate ourselves on the application of DNA sequencing technology to fermented food product probiotic count analysis and what opportunities and limitations this methodology may offer versus traditional plating techniques.”

- Published in Science

What’s the Actual Probiotic Count of Commercial Kefir?

A new peer-reviewed study from researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic count and “contained species not included on the label.”

Kefir, widely consumed in Europe and the Middle East, is growing in popularity in the U.S. Researchers examined the bacterial content of five kefir brands. Their results, published in the Journal of Dairy Science, challenge the “probiotic punch” the labels claim.

“Our study shows better quality control of kefir products is required to demonstrate and understand their potential health benefits,” says Kelly Swanson, professor in human nutrition in the Department of Animal Sciences and the Division of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Illinois. “It is important for consumers to know the accurate contents of the fermented foods they consume.”

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs). The more probiotics, the greater the health benefit.

According to a news release from the University of Illinois: “Most companies guarantee minimum counts of at least a billion bacteria per gram, with many claiming up to 10 or 100 billion. Because food-fermenting microorganisms have a long history of use, are non-pathogenic, and do not produce harmful substances, they are considered ‘Generally Recognized As Safe’ (GRAS) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and require no further approvals for use. That means companies are free to make claims about bacteria count with little regulation or oversight.”

To perform the study, the researchers bought two bottles of each of five major kefir brands. Bottles were brought to the lab where bacterial cells were counted and bacterial species identified. Only one of the brands studied had the amount of probiotics listed on its label.

“Just like probiotics, the health benefits of kefirs and other fermented foods will largely be dependent on the type and density of microorganisms present,” Swanson says. “With trillions of bacteria already inhabiting the gut, billions are usually necessary for health promotion. These product shortcomings in regard to bacterial counts will most certainly reduce their likelihood of providing benefits.”

The news release continues:

When the research team compared the bacteria in their samples against the ones listed on the label, there were distinct discrepancies. Some species were missing altogether, while others were present but unlisted. All five products contained, but didn’t list, Streptococcus salivarius. And four out of five contained Lactobacillus paracasei.

Both species are common starter strains in the production of yogurts and other fermented foods. Because those bacteria are relatively safe and may contribute to the health benefits of fermented foods, Swanson says it’s not clear why they aren’t listed on the labels.

Although the study only tested five products, Swanson suggests the results are emblematic of a larger issue in the fermented foods market.

“Even though fermented foods and beverages have been important components of the human food supply for thousands of years, few well-designed studies on their composition and health benefits have been conducted outside of yogurt. Our results underscore just how important it is to study these products,” he says. “And given the absence of regulatory scrutiny, consumers should be wary and demand better-quality commercial fermented foods.”

Q&A: Sophie Burov, Secret Lands Farm

When Sophie and Alexander Burov moved to Toronto, Canada, from Moscow, Russia, in 2007, farming wasn’t on their radar. Both entrepreneurs — she in fashion, he in mining — they were accustomed to life in one of the biggest cities in the world, not to rural farming. And their knowledge of fermented dairy was limited to taste — Alexander loved the tangy kefir he’d been drinking since childhood; Sophie devoured cheese and yogurt.

Sophie was a sheep’s milk aficionado, having tried it years earlier, She had fallen in love with its flavor, but soon learned how hard it was to find fresh sheep’s milk, especially in her native Russia. So when she met a producer at a farmer’s market in Canada, Sophie felt inspired to make her own sheep’s milk products.

“At that moment, I couldn’t even imagine running a farm,” Sophie says. She volunteered at a local dairy and sheep farm, quickly learning that: “Business is business and farming is business too, but it’s love as well. Farming is a lot of love.”

Today, Sophie, Alexander and their son Roman run the 150-acre Secret Lands Farms, south of Owen Sound in Ontario, Canada. Utilizing old-world European farming traditions, they produce a range of artisanal sheep’s milk dairy products at their on-site creamery: kefir, two varieties of yogurt, and 25 cheeses. Their kefir — made from centuries-old Tibetian grains — is also the base for their cheeses. Secret Lands is the only producer in Canada (and one of few in North America) using kefir grains as a culture for cheese.

“Seeing is believing — but tasting is falling in love,” Sophie says. “When you taste our product, you can feel the love.”

Sophie recently spoke with TFA; below are highlights from the interview.

The Fermentation Association: You purchased the farm seven years ago. Farming is hard work! Tell me what made you decide to purchase a farm?

Sophie Burov: Yes, we purchased it in 2013. The idea came about eight years ago. You know sometimes when you reach a point when you need to reconsider the purpose of your life and what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, what’s the purpose of your existing?

The agricultural sector is huge in Canada but not dairy sheep farming , so I started thinking about it as a hobby farm and we’d still live in the city, but it turned in a different direction because if you want just a hobby, it will only be your hobby. If you want something serious, your life and dedication is different when it’s your life. I believe it’s from guidance from God, I was praying a lot.

Looking back, this is the hardest job me and my husband have ever done. But it’s rewarding mentally. I believe in the spirit of the land and the animals and what you’re doing through the product you give to people, you become a bridge connection between the land and the people. Through the product, you can tell much more than through words.

If you want to go farming for money and there’s no love between you and the animals, forget it. There has to be love between you and the animals. Everyday they are teaching us how to be better human beings because sheep are very social. They are also very appreciative animals. They give back their love. If they’re struggling, you’re struggling with them.

We were very, very lucky, because we found the first sheep dairy farmers and breeders in North America — Axel Meister and his wife, Chris Buschbeck [owner of WoolDrift Farm in Markdale, Grey County, Ontario]. They brought this flock from Germany in the middle of the ‘80s and they started developing this flock in the middle of North America. When we decided to do this farm, we met Axel and started going to his farm and volunteering and he was guiding us, telling us what books to read and what to pay attention to with the sheep. His wife Chris is a vet for sheep and she helps us with our sheep.

TFA: How long did it take you to become experts at sheep farming?

SB: We are still learning. The first three years were extremely, extremely difficult. It was a hard time because, working as a volunteer at these different farms, it was very different compared to doing it yourself because all the ups, they’re yours, and all the downs, they’re yours.

TFA: Where do you sell your products?

SB: We sell at the farmers market on Saturday and home delivery twice a week. I believe home delivery is another bridge between the customers and us. If they have questions, we’re always here to answer. It’s not the easiest way to do it, but I believe that for small farmers and small producers, it’s the best way to connect with your customers and make money. We tried to work with retail stores, but retail chains, they are squeezing you. There’s no money for small farms. You can increase your flock, your production, to make more money, but we do not wish to become huge. For now it’s an ideal model for us to sell through online sales to all of the Canadanian provinces

TFA: What is a typical day like at the farm?

SB: Everyday is different. From the beginning, we were working like slaves. It was very unhealthy, all of us were sleeping just an hour, working at the farm then driving to the farmers market. Sometimes our working time was 22 hours a day, it was killing us. But now it’s easier because we have people who can help us in production and my husband Alex has people helping him on the farm, so it’s a little easier. [Secret Lands has anywhere from 8-10 employees, depending on the season].

The most difficult period of the year is lambing season. My husband and son are not sleeping at all. They have naps, but then they’re back to the barn. We do lambing once a year for a few months in spring. We do not do artificial insemination, we do it the way nature intended. The sheep are pasture-raised, grass-fed and no hormones.

TFA: You are Russian natives, where kefir originates from. Did you have kefir before starting the farm?

SB: Yes, kefir started in Russia, it began end of the 19th Century. It came from the Caucasus Mountains. But to be honest, when I started thinking about farming and a sheep dairy farm, I didnt even think about kefir, I was thinking about just yogurt because at that moment I was a yogurt and cheese person. I have hated kefir since I was a kid. My husband has been loving it since he was born.

But when we met our sheep breeder, at that moment he gave me a glass of kefir at his farm. He was just producing kefir for himself, I tried it and thought this was interesting. He gave me a handful of kefir grains, and I made kefir and brought it to our church community for people to try and share with people our idea of what we would be doing on the farm. One lady started asking me so many questions about kefir. And I realized my knowledge about kefir is null. I went back home and started my research and I was just shocked. It was so amazing, it was my ah-ha moment. Kefir is incomparable with yogurt in nutrition. Then my amazement was doubled, tripled, because sheep’s milk kefir, the product is different, the amount of calcium is much higher than cow’s or goat’s milk. In the kefir variation, our body will assimilate twice the calcium and protein.

The real kefir — made from kefir grains — it’s very limited on the market because it’s difficult to make. Seven years ago I had a handful of kefir grains, but now I can produce nine pails of 15 liters each of kefir at the same time. It’s not a huge amount actually if we compare it to someone who does it commercially. It’s impossible to make money with that amount of product. When people ask why our product is high priced, I tell them because it’s the real stuff.

TFA: Tell me some of the benefits of sheep’s milk kefir.

SB: It’s a natural probiotic, it’s the most natural probiotic in the whole world. Some scientists are saying it has 50 different variations of probiotics.

If you are taking pills or taking kefir from commercial cultures, you are not digesting the good bacteria. But if you take the real kefir, it’s becoming you and it works. People ask “Why am I supposed to drink it all the time? What’s the reason?” I tell them even the best troops in the whole world can do a lot, but if you are not feeding them, they become weak. These troops are fighting the bacteria in your body and they’re fighting nonstop, invisibly fighting bad bacteria in your body. People need to understand there’s no miracle. You can’t drink a glass or a liter and that’s all. You need to do it constantly and it will give you the health benefits from the nutrients and vitamins. I drink half a glass for my breakfast and and half a glass at night.

In kefir, your body assimilates the nutrients and vitamins. Sheep’s milk is easier to digest because it’s closest to mother’s milk, more than goat or cow milk — it’s a superior milk. You can even freeze this milk, we freeze it for the winter time and when you defrost it, it doesnt change the structure. The globule of the fat in sheeps milk is four times smaller than cow’s milk. It’s easiest to digest for people, especially with lactose issues. Same with our cheese made from kefir, it has the same benefits.

TFA: What about your other fermented products? Tell me about the baked milk yogurt.

SB: The baked milk yogurt can be confusing to people because they say “Doesn’t it kill all the probiotics in your yogurt?” No, we are slow cooking it, and then we add cultures. It is Russian and Ukrainian, this process of making yogurt. It goes back to history when people in villages were baking bread in a wooden oven. It was always pre-heated, they would put milk in a cast iron pot or clay pot. It would stay there overnight, and the water is evaporating and the milk sugar is caramelizing. We call it the healthiest creme brulee. It has the taste of caramel, but no sugar or caramel added because of the process of the caramelization of the lactose.

TFA: You make traditional yogurt, too?

SB: Yes, we are working with cultures from Italy. I tried to work with what’s available here, but it gave me a really sour, tart taste. It was too genetically modified, and that genetically modified culture is not allowed in Europe. We’re bringing all our cultures for our yogurt from Europe.

TFA: Tell me more about your cheeses.

SB: We do different varieties of cheeses called kefir cheese, we use zero commercial cultures. We are using only kefir. It takes more time, it changes a little bit of the taste for the cheese, but it’s the same culture. We’re able to produce fresh cheese to a few-years-old Pecorino. But it’s the same culture.

David Archer, he wrote The Art of the Natural Cheesemaker, I met him just before we started making kefir cheese. At that moment, his book had just released and people introduced us at the farmers market. He came to our farm and we spent a month together in our small-size commercial kitchen and creamery and he helped convert everything to kefir cheeses.

I’m always asking people just think about the history of the cheesemaking, cheesemakers they didn’t use the cultures from the lab, it was a natural fermentation. It was the same farm with the same bacteria, they’ve been doing different varieties of cheese, but it depends on your region because the environment is different. Sometimes, you don’t know what’s involved because the weather is different, the humidity is different and even our mood is different. If you’re not in a good mood, it comes out in the cheese.

Same with kefir cheese, we’re using the same kefir as a culture for our milk, and it gives us different results. Even with our soft-ripened cheeses, Camembert and Brie, the rind we are growing, it does not have any artificial bacteria that people put on top of the cheese to grow a rind. Kefir gives this ability to grow the rind naturally. But you need to be thoughtful and it involves a lot of labor because you need to keep your eye on the cheese everyday to see what’s growing on top. And you need to develop the right bacteria for the rind of the cheese.

TFA: Is the process to make a kefir cheese different from a traditional cheese?

SB: A little bit, but now much. The process to make it takes more time than traditional cheesemaking because you need to add kefir and wait. But it’s worth it because it’s a superior food that brings you all the good protein. It’s easier to digest compared to even meat because it’s naturally fermented.

TFA: How long did it take you to perfect these recipes?

SB: It’s an ongoing process. From the beginning I didn’t plan to do 25 cheeses. But I was surprised, people started asking me at the farmers market if I would make hard cheese. Now Pecorino is our top seller and our main product, it’s a sheep’s milk cheese made of full-fat, whole sheep’s milk.

Sometimes people are suspicious — “Oh a Russian, doing Pecorino in Canada?” But when they taste it, they love it.

Even as small producers, we are like big producers, because we are doing a big range of products. We have four more cheeses planned for the future. The sheep’s milk gouda is in the aging room now.

TFA: How does the taste of a fermented sheep’s milk product taste compared to fermented goat or cow dairy?

SB: Sheep’s milk is very sweet and high in fat, but good fat. It’s very smooth and creamy. My first impression when I tried a glass of sheep’s milk, it was like I was drinking the best cow’s cream of my life. It’s rich, but not heavy because the globule of the fat is very small. It gives richness, but at the same time, lightness. It’s so full of the different nodes of the taste. It’s sweet but not overly sweet, it’s balanced. The quality of the milk affects all the range of the products that we do.

Sheep milk is a very good balance between rich and light.This taste goes through the product. It’s totally different from goat milk, it doesn’t have a strong taste. Many people don’t like the taste of goat milk, the smell and taste. Sheep doesn’t have that strong taste at all.

TFA: I love that you are very invested in the welfare of your animals.

SB: For me the most important, I care how people are treating the animals. If the animals are healthy, free-range, pasture-raised, people are taking good care of them, they’re not giving them chemical-produced silo. We’re giving our animals fermented hay because it’s easier to digest. Year-round, our animals are grass-fed. We are not just farmstead producers, we are much more. Our main concern is the health of our soil. The quality of the product, the health of the product, it starts from the health of our lamb. Only good soil can guarantee good health for your animals.

TFA: Where do you see the future of fermented products?

SB: I believe in the future of fermentation. However, it’s not easy. For example, back in Russia, back in Europe, my family we’ve been doing sauerkraut since I can remember. Even here in Canada, living in downtown Toronto, even when we were in a condo, I was making sauerkraut. And kombucha.

But people are losing that connection to their food. They need the right guidance to reconsider their eating habits. I believe it will take some time to change, but we are optimistic.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

The Many Sides of Kefir

When Julie Smolyansky began working at her family’s Lifeway Foods business, her father advised her: “Don’t talk about the bacteria. People in America freak out about the bacteria on their food.” So when Lifeway became the first company in the U.S. to put “probiotic” on a label in 2003, it wasn’t a big surprise when customers began calling, asking for the company’s non-probiotic version of kefir.

Americans have come a long way. Consumers today search for the “live, cultured” label on fermented dairy, and gut health is a critical component of the modern diet. Smolyansky and Raquel Guajardo, author/educator, shared their thoughts on kefir during the TFA webinar The Many Sides of Kefir.

“Fermented foods were not part of the American diet, and the way that kefir and fermented foods in general were used in other parts of the world from Asian to Eastern Europe to even India and Mexico, these cultures all have fermented foods as one of their pillars as their foods sources and their health and wellness cultures,” Smolyansky says. “It wasn’t until immigration from all these other countries that we started talking about kimchi or kefir or lassi or you name your cultured kind of special food.”

In the U.S., the average person consumes 9-10 cups of fermented dairy a year. Contrast that statistic with Europe, where the average consumption is 28 cups a month.

“When you’re born consuming it and you’ve developed that taste palette, then it’s very easy to play in the space and have a diet that’s very rich in probiotics and kefir and all sorts of other fermented foods,” Smolyansky says, adding that the situation is changing in the U.S. Now, “people are hungry for it, they want it, once they learn about it, once they taste it, they fall in love with it, they’re hooked.”

Lifeway’s kefir’s sales have soared. The company was valued at $12 million when Smolyansky took over in 2002 — now it’s valued into the hundreds of millions. And even more customers have found kefir during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they adopt healthier lifestyles.

Guajardo has seen her online classes increase during COVID. The Mexico-based educator co-authored the book “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond” with Alex Lewin, TFA advisory board member, who moderated the webinar.

“People say ‘You’re crazy, why do you teach what to do at home what you can buy in the supermarket?’ But my business has been growing that way,” she says, adding that health benefits are the main selling point for her classes. “Why would people buy sauerkraut or kefir if you’re not explaining the benefits?”

Dairy Kefir vs. Water Kefir

Guajardo, who makes both dairy kefir and water kefir (also known as tibicos) stresses that the grains used to make each are “totally different.” Kefir grains are living bacteria and yeast microorganisms clumped together with milk proteins and sugars. They are gelatinous and white, almost like cottage cheese. Water kefir grains are also made from living bacteria and yeast microorganisms, but they’re clumped together with sugar and have a translucent, crystal-like appearance.

“Water kefir” is not the appropriate term, Guajardo and Smolyansky agree, instead calling it by its traditional Mexican name, tibicos. And they feel that using kefir or tibicos grains in coconut or almond milk and calling it kefir is also inappropriate. Smolyansky favors using a description like cultured coconut milk or beverage, but not kefir.

The National Dairy Council and Codex Alimentarius, the international food code, both state kefir is a fermented dairy product made from the milk of a lactating mammal. Smolyansky points to the many peer-reviewed studies on kefir, verifying it is full of probiotics and nutrients. Water kefir and non-dairy kefir have not been studied, and can’t guarantee the same health benefits.

“Just by throwing the name onto anything and just bastardizing the definition, we completely dilute any of the research that’s ever been done [on kefir], it would dilute the history, the folklore. So we are very passionate about protecting the name,” Smolyansky says. “My ancestors made sure that kefir survived for 2,000 years, and it’s critical that we don’t dilute it now that it’s having a moment, now that it’s popular.”

Smolyansky’s family emigrated to the United States from the then Soviet Union in the late ‘70s. Her father, Michael, began Lifeway Foods in Chicago in 1986.

“We have to respect the standards and what these definitions mean or it will be the Wild West and people won’t know what they’re buying,” she adds. She shares the labelling of ice cream as an example — ice cream is considered dairy while non-dairy products have other names, like sorbet, gelato or non-dairy frozen dessert.

Can Kefir Grow Like Yogurt?

Yogurt has paved the way for kefir to expand its consumer base in the U.S. Both are fermented dairy products with tangy tastes. But for kefir to achieve widespread, mainstream adoption like yogurt, significant education is needed. Thousands of peer-reviewed studies prove kefir contains a higher concentration of probiotics than yogurt — and a wider range of beneficial bacteria. For kefir to grow, this message needs to reach consumers.

“It’s a different set of microbes,” Lewin says. “Kefir is fermented with yeast and yogurt isn’t. Kefir has a larger family of microbes.”

Smolyansky is passionate that kefir cannot be compared to the products of the major. yogurt companies.

“The yogurt produced in the United States is so over-produced and so over-pasteurized that there’s practically nothing living in it after it’s been processed,” she says. “It’s one of the biggest problems with yogurt in the U.S.”

Lifeway regularly sends their products to be tested for probiotics, measuring Colony Forming Units (CFUs), the active microorganisms in a food product. Smolyansky says eating probiotics is critical in a germ-phobic, antibody-heavy society, where we’re over-sanitizing due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“If our bodies aren’t fighting an outside kind of pathogen, it starts to fight itself,” she says. “One of the ways to counteract this disruption in our microflora is by the use and the introduction of consistently replenishing microflora including diversity of bacteria, a variety of food sources that offer bacteria, the diversity and kind [of bacteria] is always the king. It makes for great food environments in the gut.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

“One Grain to Bind Them All”

A new study on kefir found that the individual dominant species of Lactobacillus bacteria in kefir grains cannot survive in milk on their own. The bacteria need one another to create the fermented dairy drink, “feeding on each other’s metabolites in the kefir culture.”

The research, conducted by EMBL (Europe’s laboratory for life and sciences) and Cambridge University’s Patil group and published in Nature Microbiology, illustrates a dynamic of microbes that had eluded scientists. Though scientists knew microorganisms live in communities and depend on each other to survive, “mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited,” according to a press release on the research.

“Cooperation allows them to do something they couldn’t do alone,” says Kiran Patil, group leader and author of the paper. “It is particularly fascinating how L. kefiranofaciens, which dominates the kefir community, uses kefir grains to bind together all other microbes that it needs to survive — much like the ruling ring of the Lord of the Rings. One grain to bind them all.”

To make kefir, it takes a team. A team of microbes.

The group studied 15 samples of kefir, one of the world’s oldest fermented food products. Below are highlights from a press release on the published results.

A Model of Microbial Interaction

Kefir first became popular centuries ago in Eastern Europe, Israel, and areas in and around Russia. It is composed of ‘grains’ that look like small pieces of cauliflower and have fermented in milk to produce a probiotic drink composed of bacteria and yeasts.

“People were storing milk in sheepskins and noticed these grains that emerged kept their milk from spoiling, so they could store it longer,” says Sonja Blasche, a postdoc in the Patil group and an author of the paper. “Because milk spoils fairly easily, finding a way to store it longer was of huge value.”

To make kefir, you need kefir grains, which must come from another batch of kefir. They cannot be made artificially. The grains are added to milk, to ferment and grow. Approximately 24 to 48 hours later (or, in the case of this research, 90 hours later), the kefir grains have consumed the available nutrients. The grains have grown in size and number, and are removed and added to fresh milk — to begin the process anew.

For scientists, kefir is more than just a healthy beverage: it’s an easy-to-culture model microbial community for studying metabolic interactions. And while kefir is quite similar to yogurt in many ways – both are fermented or cultured dairy products full of ‘probiotics’ – kefir’s microbial community is far larger, including not just bacterial cultures but also yeast.

A “Goldilocks Zone”

While scientists know that microorganisms often live in communities and depend on their fellow community members for survival, mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited. Laboratory models historically have been limited to two or three microbial species, so kefir offers – as Patil describes – a ‘Goldilocks zone’ of complexity that is not too small (around 40 species), yet not too unwieldy to study in detail.

Blasche started this research by gathering kefir samples from several sources. Though most were obtained in Germany, they may have originated elsewhere, grown from kefir grains passed down through the years..

“Our first step was to look at how the samples grow. Kefir microbial communities have many member species with individual growth patterns that adapt to their current environment. This means fast- and slow-growing species and some that alter their speed according to nutrient availability,” Blasche says. “This is not unique to the kefir community. However, the kefir community had a lot of lead time for coevolution to bring it to perfection, as they have stuck together for a long time already.”

Cooperation is key

Finding out the extent and nature of cooperation among kefir microbes was far from straightforward. Researchers combined a variety of state-of-the-art methods, such as metabolomics (studying metabolites’ chemical processes), transcriptomics (studying the genome-produced RNA transcripts) and mathematical modelling. These processes revealed not only key molecular interaction agents like amino acids, but also the contrasting species dynamics between grains and milk.

“The kefir grain acts as a base camp for the kefir community, from which community members colonise the milk in a complex yet organised and cooperative manner,” Patil says. “We see this phenomenon in kefir, and then we see it’s not limited to kefir. If you look at the whole world of microbiomes, cooperation is also a key to their structure and function.”

In fact, in another paper from Patil’s group (in collaboration with EMBL’s Bork group) in Nature Ecology and Evolution, scientists combined data from thousands of microbial communities across the globe – from in soil to in the human gut – to understand similar cooperative relationships. In this second paper, the researchers used advanced metabolic modelling to show that the co-occurring groups of bacteria, groups that are frequently found together in different habitats, are either highly competitive or highly cooperative. This stark polarization hadn’t been observed before, and sheds light on evolutionary processes that shape microbial ecosystems. While both competitive and cooperative communities are prevalent, the cooperators seem to be more successful in terms of higher abundance and occupying diverse habitats — stronger together!

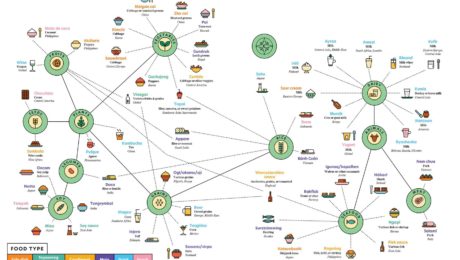

The World of Fermented Foods

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor