“Our Customers Do Not Even Know What is a Fermented Item”

Fermentation is cloaked in mystery for many — it’s bubbly, slimy, stinky and not always Instagram-ready. In The Fermentation Association’s recent member survey, this lack of

understanding of fermentation and its flavor and health attributes among consumers was cited by 70% of producers as a major obstacle to increased sales and acceptance of fermented products.

“We get so many questions from our readers about fermentation. People are very interested, but have very, very little knowledge about it,” says Anahad O’Connor, reporter for The New York Times. O’Connor has written about fermented foods multiple times in the last few months, and those articles were among The Times’ most emailed pieces of 2021. “I think there’s a huge opportunity to educate consumers about fermented foods, their impact on the gut and health in general.”

O’Connor spoke on consumer education as part of a panel of experts during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. Panelists — who included a producer, retailer, scientist, educator and journalist — agreed consumer education is lacking. But the methods of how to fill that gap are contested.

How to Tell Consumers “What is a Fermented Food?”

There are differences between what is a fermented product and what is not — a salt brine vs. vinegar brine pickle, or a kombucha made with a SCOBY or one from a juice concentrate, for example.

“I can tell you that the majority of our customers do not even know [what is a] fermented item,” says Emilio Mignucci, vice president of Philadelphia gourmet store Di Bruno Bros., which specializes in cheese and charcuterie. When customers sample products at the store, they can easily taste the differences between a fermented and a non-fermented product, Mignucci says. But he feels the health benefits behind that fermented product are not the retailer’s responsibility to communicate. “I need you guys [producers] to help me deliver the message.”

“Retailers like myself, buyers, we want to learn more to be able to champion [fermented foods] because, let’s face it, fermented foods is a category that’s getting better and better for us as retailers and we want to speak like subject matter experts and help our guests understand.”

Now — when fermentation tops food lists and gut health is mainstream — is the time for education.

“This microbiome world that we’re in right now is sort of a really opportune moment to really help the public understand what fermented foods are beyond health,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member).

Kombucha Brewers International (KBI) created a Code of Practice to address confusion over what is or is not a kombucha. KBI is taking the approach that all kombucha is good, pasteurized or not, because it’s moving consumers away from sugar- and additive-filled sodas and energy drinks.

“That said, consumers deserve the right to know why is this kombucha at room temperature and this kombucha is in the fridge and why does this kombucha have a weird, gooey SCOBY in it and this one is completely clear,” says Hannah Crum, president of KBI. “They start to get confused when everything just says the word ‘kombucha’ on it.”

KBI encourages brewers to be transparent with consumers. Put on the label how the kombucha is made, then let consumers decide what brand they want to buy.

Should Fermented Products Make Health Claims?

Drew Anderson, co-founder and CEO of producer Cleveland Kitchen (and also on TFA’s Advisory Board), says when they were first designing their packaging in 2013, they were advised against using the term “crafted fermentation” on their label because it would remind consumers of beer or wine. But nowadays, data shows 50% of consumers associate the term fermentation with health.

“In the last five to six years, it’s changed dramatically and people are associating fermentation as being good for them, which is good for my products,” he says.

Cleveland Kitchen, though, does not make health claims on their fermented sauerkraut, kimchi and dressings. Anderson says, as a small startup, they don’t have the resources to fund their own research. They instead attract customers with bold taste and striking packaging.

“We’re extremely cautious on what we say on the package because we don’t have an army of lawyers like Kevita (Pepsi’s Kombucha brand), we don’t have the Pepsi legal team backing us here,” Anderson says. Cleveland Kitchen submits new packaging designs in advance to regulators, to make sure they’re legally acceptable before rolling them out.

O’Connor says taste is the No. 1 driver for consumers. This is why healthful but sticky and stinky natto (fermented soybeans) is not a popular dish in America, but widely consumed in Japan.

“Many American consumers, unfortunately, aren’t going to gravitate toward that, despite the health benefits,” he says.

Crum disagrees. “Health comes first,” she says. As more and more kombucha brands emphasize lifestyle, and don’t even advertise their health benefits, she feels they are doing a disservice to the consumer. “Why pay that much money for kombucha if you don’t know it’s good for you too?”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Fermentation Tourism

The state of Pennsylvania has created a unique tourist experience, Pickled: A Fermented Trail. The self-guided, culinary tour showcases fermented food and drink from around the state.

The fermented trail is broken into five regional itineraries, and includes historic businesses, artisanal food makers and large producers. Stops range from an Amish gift shop that ferments root beer to a master chocolatier, from a kombucha taproom to a fermentation-focused restaurant, and from a fourth-generation cheesemaker to a convenience store that makes its own pickles, sauerkraut and vinegar. Mary Miller, cultural historian and professor, spent two years designing the trail.

“Cultured foods have been part of PA’s culinary culture since the beginning,” reads the Visit Pennsylvania Pickled: A Fermented Trail website. “Many groups that have migrated to Pennsylvania throughout history were fond of fermented foods for both health and flavor, as well as for preserving food through the winter.”

The website also features a history of fermented food and drink, both regionally and globally. It shares a brief overview of root beer, which was created in Pennsylvania as a sassafras-based, yeast-fermented root tea. And it notes that, while Germans brought sauerkraut to the state, the Chinese are believed to have been the first to ferment cabbage.

The fermented trail is one of Pennsylvania’s four new culinary road trips, along with those highlighting charcuterie, apples and grains. These paths aim to showcase the state’s culinary history, and preserve its foodways.

This unique culinary adventure — the first we have seen at TFA — could be a model for tourism in other states and countries.

Read more (Food & Wine)

- Published in Business

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

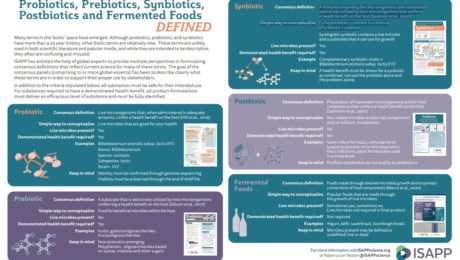

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

Fermentation in Anthropology

Fermented foods have had an impact on human evolution, and they continue to affect social dynamics, according to a new collection of 16 studies in the journal Current Anthropology. This research explores how “microbes are the unseen and often overlooked figures that have profoundly shaped human culture and influenced the course of human history.”

The journal’s special edition, Cultures of Fermentation, features work from multiple disciplines: microbiology, cultural anthropology, archaeology and biological anthropology. Researchers were based all over the globe.

“Humans have a deep and complex relationship with microbes, but until recently this history has remained largely inaccessible and mostly ignored within anthropology,” reads the introduction, Cultures of Fermentation: Living with Microbes. “Fermentation is at the core of food traditions around the world, and the study of fermentation crosscuts the social and natural sciences.”

The impetus for the articles was a 2019 symposium organized by the non-profit Wenner-Gren Foundation. This organization aims to bring together scholars to debate and discuss topics in anthropology.

“Fermentation is at the core of food traditions around the world, and the study of fermentation crosscuts the social and natural sciences,” the introduction continues. The aim of the symposium and corresponding research was to “foster interdisciplinary conversations integral to understanding human-microbial cultures. By bridging the fields of archaeology, cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, microbiology, and ecology, this symposium will cultivate an anthropology of fermentation.”

Here is a listing the included studies:

- Predigestion as an Evolutionary Impetus for Human Use of Fermented Food (Katherine R. Amato,Elizabeth K. Mallott, Paula D’Almeida Maia, and Maria Luisa Savo Sardaro). Using research on nonhuman primates, researchers conclude that “fermentation played a central role in enabling our earliest ancestors to survive in the forested grasslands in Africa where key anatomical features of our species emerged. Fermentation occurs spontaneously in nature. Most nonhuman primates cannot metabolize fermented products, but humans evolved the capacity to use them as fuel. …By breaking down tough and toxic plant species, fermentation helped humans meet the caloric requirements associated with their growing brains and shrinking guts. These anatomical changes both stemmed from and fueled the emergence of collective forms of know-how — microbial and human cultures fed on one another, in this view of the human past.”

- Toward a Global Ecology of Fermented Foods (Robert R. Dunn, John Wilson, Lauren M. Nichols, and Michael C. Gavin). This ecological view of fermentation maps the “emergence and divergence of the world’s many varieties of fermented foods.”

- Prehistoric Fermentation, Delayed-Return Economies, and the Adoption of Pottery Technology (Oliver E. Craig). Craig explores the central role of pottery in “people’s ability to amass the kinds of surpluses that allowed human communities to lay down roots.” Pots were ideal as the storage vessels that made it possible to domesticate microbes.

- Seeking Prehistoric Fermented Food in Japan and Korea (Shinya Shoda). This study focuses on fermentation’s rise in prehistoric Japan and Korea along with each country’s respective cultural achievements.

- Cultured Milk: Fermented Dairy Foods along the Southwest Asian–European Neolithic Trajectory (Eva Rosenstock, Julia Ebert, and Alisa Scheibner). Using archaeological evidence of fermentation, researchers track the “emergence of lactase persistence in sites where dairying made an early appearance. It appears that people ate cheese and yoghurt well before they drank milk: only a small subsection of the human population retains the enzymes needed to digest lactose into adulthood.”

- Missing Microbes and Other Gendered Microbiopolitics in Bovine Fermentation (Megan Tracy). Industrial dairy farms are finding “missing microbes” in cows, Tracy highlights in her study. Newborn calves are separated from their mothers in industrialized dairy farms, and thereby lose the critical gut connections that would have been made by drinking breast milk.

- Living Machines Go Wild: Policing the Imaginative Horizons of Synthetic Biology (Eben Kirksey). Kirksey profiles the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition in Boston, where living creatures made through genetic engineering tools are regarded as machines. “…life is being remade in novel and surprising ways as iGEM students use increasingly fast and cheap genetic engineering tools.”

- From Immunity to Collaboration: Microbes, Waste, and Antitoxic Politics (Amy Zhang). Research details “urban waste activists in China who are practicing a quiet form of resistance to the policies of the authoritarian state by using the fermentation of eco-enzymes to heal sickened rivers, bodies, and soils.”

- The Nectar of Life: Fermentation, Soil Health, and Bionativism in Indian Natural Farming (Daniel Münster). Münster delves into agricultural politics in India. He concludes that “fermentation’s effects are unpredictable: there is always more than one story to tell.”

- Microbial Antagonism in the Trentino Alps: Negotiating Spacetimes and Ownership through the Production of Raw Milk Cheese in Alpine High Mountain Summer Pastures (Roberta Raffaetà). Raffaetà investigates cheesemaking in the Italian alps, contrasting three different approaches — farmers who don’t use contemporary cheesemaking methods and only use microbes found in their terroir, , industrialized cheese producers,; and high-mountain farmers who mix cheesemaking elements from different times, such as using a standardized starter with local cultures.

- Protecting Perishable Values: Timescapes of Moving Fermented Foods across Oceans and International Borders (Heather Paxson). Raw milk cheese, cured meats and assorted ferments get their flavor from microbes. Paxson documents how transportation and distribution can erode the microbial content of these products, especially international imports. She concludes supply chains (especially international) should be further explored to make transporting products with live microbes viable.

- Enduring Cycles: Documenting Dairying in Mongolia and the Alps (Björn Reichhardt, Zoljargal Enkh-Amgalan,Christina Warinner, and Matthäus Rest). This research details the Dairy Cultures Ethnographic Database, an open resource featuring photos and videos of dairy production, landscapes and livestock in the Alps. Interviews, oral histories and folk songs are also included.

- Preserving the Microbial Commons: Intersections of Ancient DNA, Cheese Making, and Bioprospecting (Matthäus Rest). Rest traces the history and spread of dairying in Mongolia, Europe and the Near East. She concludes by calling on scientists and local producers to protect the “microbial commons” from “patenting and commodification.”

- Taste-Shaping-Natures: Making Novel Miso with Charismatic Microbes and New Nordic Fermenters in Copenhagen (Joshua Evans and Jamie Lorimer). This research for this paper took place at Noma in Copenhagen, and studied how fermentation allows the restaurant to tread a fine line “between ecologically responsible localism and the nativism associated with the rise of Denmark’s anti-immigrant right. Noma’s chefs have hit upon kōji, Japan’s “national fungus,” which they turn loose on Danish ingredients.”

- Bamboo Shoot in Our Blood: Fermenting Flavors and Identities in Northeast India (Dolly Kikon). Kikon explores fermented bamboo, a delicacy in India, and how it’s part of the local the community.

- Fermentation in Post-antibiotic Worlds: Tuning In to Sourdough Workshops in Finland (Salla Sariola). Sariola describes fermentation “as a politically progressive form of performance art.” She documents activities in China, where fermentation is used to “challenge the modernist regimes of purification that have turned microbes into the enemy. To learn to live better with microbes is to learn to live better with other kinds of difference — those associated with ethnicity, race, national origins, sexual orientation, ability, and age.”

- Published in Science

The São Jorge Cheese

On the remote, volcanic island of São Jorge in the middle of the Atlantic is what Insider calls “Portugal’s best-kept secret” — its eponymous cheese.

The weather conditions on the island make it perfect for cheesemaking, an art that began there 500 years ago. It’s humid, so cheese can rest at room temperature, packing the cheese with moisture. Cows (there are over 10,000 on the island, double the number of the human inhabitants) can graze year round.

São Jorge cheese is rich, with “hints of spiciness, and a grassy scent.” One of four dairy farmers on the island, João, ascribes the flavor to the cheesemaking process, which preserves “the flavors of the island in the cheese by not killing the native cultures that are present in the milk.” The milk is kept raw, unpasteurized and whey from the day before is used to ferment the milk instead of adding fermenting agents.

Read more (Insider)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Primeval Poop Profiles

Studies of ancient poop found “humans as long as 2,700 years ago in the Iron Age were already using sophisticated techniques in flavoring the fermented foods.” They especially loved pairing pale ale with blue cheese.

A paper published in Current Biology detailed how researchers used paleo fecal samples found in salt mines in Austria to analyze the food ancient people were consuming. Their stool dehydrated in the salt, creating an ideal, preserved sample.

Researchers from the Institute for Mummy Studies, the University of Trento and the Vienna Museum of Natural History also found industrialization transformed the Western diet. Humans used to have healthier, more biodiverse gut microbiomes “because they were eating unprocessed foods.”

Frank Maixner, one of the paper’s lead authors, believes combining archaeology and microbiology could “illuminate the greater puzzle of human history.”

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Chhurpi — Cheese from Chauri

Have you heard of chhurpi, the world’s hardest cheese? Developed thousands of years ago in a remote Himalayan village, it’s made from milk from a chauri (a cross between a male yak and a female cow) and is a favorite snack in pockets of eastern India, Nepal and Bhutan.

The protein-rich, low-fat cheese gets softer the longer it’s chewed — and people will chew on small cubes for hours. Chhurpi has low moisture content, making it edible for up to 20 years. It’s used in curries and soups or chewed as a snack (especially by yak herders during their long travels).

Chhurpi is fermented for 6-12 months, then stored in animal skin. It’s healthy and nutrient-rich, as chauri graze on herbs and grass in the high alpine mountains.

“It is said hard chhurpi takes anything between minutes to hours to soften, after which it tastes like a dense milky solid with a smoky flavour as it dissolves slowly. The so-called world’s hardest cheese is admittedly not everyone’s cup of tea, and I never could bite into one so far, but Nepalis across the country adore it,” writes BBC writer Neelima Vallangi.

Read more (BBC)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality

Fermented foods are produced through controlled microbial growth — but how do industry professionals manage those complex microorganisms? Three panelists, each with experience in a different field and at a different scale — restaurant chef, artisanal cheesemaker and commercial food producer — shared their insights during a TFA webinar, Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality.

“Producers of fermented foods rely on microbial communities or what we often call microbiomes, these collections of bacteria yeasts and sometimes even molds to make these delicious products that we all enjoy,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University, who moderator the webinar along with Maria Marco, PhD, professor at University of California, Davis (both are TFA Advisory Board members).

Wolfe continued: “Fermenters use these microbial communities every day right, they’re working with them in crocks of kimchi and sauerkraut, they’re working with them in a vat of milk as it’s gone from milk to cheese, but yet most of these microbial communities are invisible. We’re relying on these communities that we rarely can actually see or know in great detail, and so it’s this really interesting challenge of how do you manage these invisible microbial communities to consistently make delicious fermented foods.”

Three panelists joined Wolfe and Marco: Cortney Burns (chef, author and current consultant at Blue Hill at Stone Barns in New York, a farmstead restaurant), Mateo Kehler (founder and cheesemaker at Jasper Hill in Vermont, a dairy farm and creamery) and Olivia Slaugh (quality assurance manager at wildbrine | wildcreamery in California, producers of fermented vegetables and plant-based dairy).

Fermentation mishaps are not the same for producers because “each kitchen is different, each processing facility, each packaging facility, you really have to tune in to what is happening and understand the nuance within a site,” Marco notes. “Informed trial and error” is important.

The three agreed that part of the joy of working in the culinary world is creating, and mistakes are part of that process.

“We have learned a lot over the years and never by doing anything right, we’ve learned everything we know by making mistakes,” says Kehler.

One season at Jasper Hill, aspergillus molds colonized on the rinds of hard cheeses, spoiling them. The cheesemakers discovered that there had been a problem early on as the rind developed. They corrected this issue by washing the cheese more aggressively and putting it immediately into the cellar.

“For the record, I’ve had so many things go wrong,” Burns says. A koji that failed because a heating sensor moved, ferments that turned soft because the air conditioning shut off or a water kefir that became too thick when the ferment time was off. “[Microbes are] alive, so it’s a constant conversation, it’s a relationship really that we’re having with each and every one on a different level, and some of these relationships fall to the wayside or we forget about them or they don’t get the attention they need.”

Burns continues: “All these little safeguards need to be put in place in order for us to have continual success with what we’re doing, but we always learn from it. We move the sensor, we drop the temperature, we leave things for a little bit longer. That’s how we end up manipulating them, it’s just creating an environment that we know they’re going to thrive in.”

Slaugh distinguishes between what she calls “intended microbiology” — the microbes that will benefit the food you’re creating — and “unintended microbiology” — packaging defects, spoilage organisms or a contamination event.

Slaugh says one of the benefits of working with ferments at a large scale at wildbrine is the cost of routine microbiological analysis is lower. But a mistake is stressful. She recounted a time when thousands of pounds of food needed to be thrown out because of a contaminant in packaging from an ice supplier.

“Despite the fact that the manufacturer was sending us a food-grade or in some cases a medical-grade ingredient, the container does not have the same level of sanitation, so you can’t really take these things for granted,” Slaugh says.

Her recommendations include supplier oversight, a quality assurance person that can track defects and sample the product throughout fermentation and a detailed process flow diagram. That document, Slaugh advises, should go far beyond what producers use to comply with government food regulations. It should include minutiae like what scissors are used to cut open ingredient bags and the process for employees to change their gloves.

“I think this is just an incredible time to be in fermented foods,” Kehler adds. “There’s this moment now where you have the arrival of technology. The way I described being a cheesemaker when I started making cheese almost 20 years ago was it was like being a god, except you’re blind and dumb. You’re unleashing these universes of life and then wiping them out and you couldn’t see them, you could see the impacts of your actions, but you may or may not have control. What’s happened since we started making cheese is now the technology has enabled us to actually see what’s happening. I think it’s this groundbreaking moment, we have the acceleration of knowledge. We’re living in this moment where we can start to understand the things that previously could only be intuited.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Fermentation vs. Fiber — Both Help, but Fermentation Shines

A diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response, according to researchers at Stanford University’s School of Medicine.The groundbreaking results were published in the journal Cell.

In the clinical trial, healthy individuals were fed for 10 weeks, a diet either high in fermented foods and beverages or high in fiber. The fermented diet — which included yogurt, kefir, cottage cheese, kimchi, kombucha, fermented veggies and fermented veggie broth — led to an increase in overall microbial diversity, with stronger effects from larger servings.

“This is a stunning finding,” says Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford. “It provides one of the first examples of how a simple change in diet can reproducibly remodel the microbiota across a cohort of healthy adults.”

Researchers were particularly pleased to see participants in the fermented foods diet showed less activation in four types of immune cells. There was a decrease in the levels of 19 inflammatory proteins, including interleukin 6, which is linked to rheumatoid arthritis, Type 2 diabetes and chronic stress.

“Microbiota-targeted diets can change immune status, providing a promising avenue for decreasing inflammation in healthy adults,” says Christopher Gardner, PhD, the Rehnborg Farquhar Professor and director of nutrition studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center. “This finding was consistent across all participants in the study who were assigned to the higher fermented food group.”

Microbiota Stability vs. Diversity

Continues a press release from Stanford Medicine News Center: By contrast, none of the 19 inflammatory proteins decreased in participants assigned to a high-fiber diet rich in legumes, seeds, whole grains, nuts, vegetables and fruits. On average, the diversity of their gut microbes also remained stable.

“We expected high fiber to have a more universally beneficial effect and increase microbiota diversity,” said Erica Sonnenburg, PhD, a senior research scientist at Stanford in basic life sciences, microbiology and immunology. “The data suggest that increased fiber intake alone over a short time period is insufficient to increase microbiota diversity.”

Justin and Erica Sonnenburg and Christopher Gardner are co-authors of the study. The lead authors are Hannah Wastyk, a PhD student in bioengineering, and former postdoctoral scholar Gabriela Fragiadakis, PhD, now an assistant professor of medicine at UC-San Francisco.

A wide body of evidence has demonstrated that diet shapes the gut microbiome which, in turn, can affect the immune system and overall health. According to Gardner, low microbiome diversity has been linked to obesity and diabetes.

“We wanted to conduct a proof-of-concept study that could test whether microbiota-targeted food could be an avenue for combatting the overwhelming rise in chronic inflammatory diseases,” Gardner said.

The researchers focused on fiber and fermented foods due to previous reports of their potential health benefits. High-fiber diets have been associated with lower rates of mortality. Fermented foods are thought to help with weight maintenance and may decrease the risk of diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease.

The researchers analyzed blood and stool samples collected during a three-week pre-trial period, the 10 weeks of the diet, and a four-week period after the diet when the participants ate as they chose.

The findings paint a nuanced picture of the influence of diet on gut microbes and immune status. Those who increased their consumption of fermented foods showed effects consistent with prior research showing that short-term changes in diet can rapidly alter the gut microbiome. The limited changes in the microbiome for the high-fiber group dovetailed with previous reports of the resilience of the human microbiome over short time periods.

Designing a suite of dietary and microbial strategies

The results also showed that greater fiber intake led to more carbohydrates in stool samples, pointing to incomplete fiber degradation by gut microbes. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that the microbiome of a person living in the industrialized world is depleted of fiber-degrading microbes.

“It is possible that a longer intervention would have allowed for the microbiota to adequately adapt to the increase in fiber consumption,” Erica Sonnenburg said. “Alternatively, the deliberate introduction of fiber-consuming microbes may be required to increase the microbiota’s capacity to break down the carbohydrates.”

In addition to exploring these possibilities, the researchers plan to conduct studies in mice to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which diets alter the microbiome and reduce inflammatory proteins. They also aim to test whether high-fiber and fermented foods synergize to influence the microbiome and immune system of humans. Another goal is to examine whether the consumption of fermented foods decreases inflammation or improves other health markers in patients with immunological and metabolic diseases, in pregnant women, or in older individuals.

“There are many more ways to target the microbiome with food and supplements, and we hope to continue to investigate how different diets, probiotics and prebiotics impact the microbiome and health in different groups,” Justin Sonnenburg said.

Other Stanford co-authors are Dalia Perelman, health educator; former graduate students Dylan Dahan, PhD, and Carlos Gonzalez, PhD; graduate student Bryan Merrill; former research assistant Madeline Topf; postdoctoral scholars William Van Treuren, PhD, and Shuo Han, PhD; Jennifer Robinson, PhD, administrative director of the Community Health and Prevention Research Master’s Program and program manager of the Nutrition Studies Group; and Joshua Elias, PhD.

Researchers from the nonprofit research center Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub also contributed to the study. Here’s the complete press release from Stanford Medicine News Center.

Vegan Cheese Matures

Vegan cheese makers are “pushing the limits of those fermentations to create … flavors and textures I’d previously thought impossible,” writes The New York Times food columnist Tejal Rao. She says the “new generation” of vegan cheese is surprisingly tastier than the bland, starchy, mass-produced vegan cheese of the early 2000s.

Missing from those first versions of vegan cheese: fermentation, a key to creating flavor. Vegan cheese now is also aged and ripened like dairy cheese to develop flavors and textures.

The microbes used to give cheeses like Gouda and Brie their distinct flavors are also critical. Vegan cheese cultures are now readily available. Aaron Bullock and Ian Marin (pictured), founders of Misha’s Kind Foods, work with proprietary cultures to create cream cheese and ricotta made from cashew milk.

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor