Scientists Discover Which Bacteria Transfer to Gut

Scientists in Italy have discovered lactic acid bacteria in fermented food transfers to the gut microbiome. Though this is a widely accepted health benefit of fermented foods, there is little scientific research linking fermented food and the microbiome. The study looked at distribution of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in humans based on location, age and lifestyle.

LAB genomes were reconstructed from about 300 foods and nearly 10,000 human fecal samples from humans from different continents.

The most frequent LAB food in the human feces: streptococcus thermophilus and lactococcus lactis, commonly found in yogurt and cheese.

“Our large-scale genome-wide analysis demonstrates that closely related LAB strains occur in both food and gut environments and provides unprecedented evidence that fermented foods can be indeed regarded as a possible source of LAB for the gut microbiome.”

Read more (Nature Communications)

Farmer, Nutrition Activist Uses Fermentation Methods to Create Healthier School Lunches

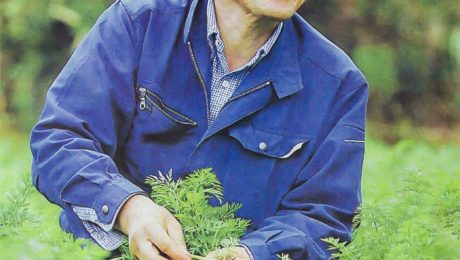

An organic farmer and nutrition activist is teaching schools and daycare centers in Japan to grow their own vegetable garden using fermented compost from recycled food waste, then incorporate into school lunches those fresh vegetables with traditional Japanese fermented foods (like miso and pickles). Two years after the program’s launch, absences due to illness have dropped from an average of 5.4 days to 0.6 days per year.

Farmer Yoshida Toshimichi “is a devout believer in the power of microbes.” Using centuries of Japanese folks wisdom that is supported by modern science, Toshimichi explains that fermentation bacteria in the compost yields hardy, insect-resistance vegetables. He says the key to a healthy immune system is maintaining a diverse and balanced gut microbiota. “Lactobacilli and other friendly microbes found in naturally fermented foods can help maintain a healthy environment in the gut, just as they do in the soil,” continues the article. Microorganisms in fermented foods like miso and soy sauce will help balance gut flora. “Organic vegetables, meanwhile, provide the micronutrients and fiber on which those friendly bacteria thrive. In addition, phytochemicals found in vegetables—especially, fresh organic vegetables in season—are thought to guard against inflammation, which is associated with cancer and various chronic diseases,” the article reads.

Toshimichi has authored books on his farming and nutrition practices and is featured in the two-part documentary film “Itadakimasu,” which translates to “nourishment for the Japanese soul.”

Read more (Nippon)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

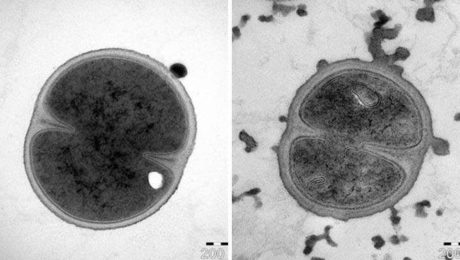

Peptide Found on Fermented Veggies Aids Antibiotics Research

Microbiologists in Sweden discovered a major breakthrough in antibiotics. Their research found an antibacterial peptide, plantarcin, can be combined with antibiotics to kill the staphylococcus bacteria (MRSA). Staph is a major problem in healthcare, which causes difficult wound infections and, in severe cases, sepsis. This plantarcin peptide comes from good bacteria — it’s found on fermented vegetables, which serve as a natural preservative for the food. The results of the study were published in the journal Scientific Reports. “Administering lower doses of antibiotics when treating infections in turn reduces the risk of further development of antibiotic resistance, which today is a major global threat to public health,” says Torbjörn Bengtsson, professor in medical cell biology at Örebro University.

Read more (Phys.org)

The Science of Yeast, the Microbe in your Pandemic Bread

Humans have been baking fermented breads for at least 10,000 years, but commercial yeast and flour companies have never seen demand so high. National Geographic shares “a story for quarantined times, about extremely tiny organisms that do some of their best work by burping into uncooked dough.”

Scientists describe the microbes behind the work fermenting the bread. “It’s this wonderful living thing you’re working with,” says Anne Madden, a North Carolina State University adjunct biologist who studies microbes. She and partner scientists showed recently that when bakers in different locales use exactly the same ingredients for both starter and bread, their loaves come out smelling and tasting different. “Which I think is fantastic,” she says. “It’s evidence of the unseen. And as a microbiologist, you so rarely get to measure things about microbes with your nose and your taste buds.”

Read more (National Geographic)

- Published in Science

How Fermented Food Affects Our Gut

Americans are hearing the term “microbiome” a lot lately. It’s become a common phrase in health food marketing. But the microbiome is still uncharted territory in science.

Dr. Shilpa Ravella, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center, says a large army of trillions of bacteria lives on or in us, and we can alter that bacteria by fueling it with the right (or wrong) foods.

“There are also ways of preparing food that can actually introduce good bacteria, also known as probiotics, into your gut. Fermented foods are teeming with helpful probiotic bacteria, like lactobacillus and bifidobacteria,” Ravella says.

Fermented food and drink are critical to caring for gut bacteria. Because fermented products are minimally processed and provide nutrient-rich variety to diets, she adds.

But that doesn’t mean all fermented products are created equally. Yogurt is a beneficial food, for example, but some brands add too much sugar and not enough beneficial bacteria that the yogurt may not actually help.

Ravella shared her insight in a TedED talk. As the director of Columbia’s Adult Small Bowel Program, she works with patients plagued by gut issues.

“We don’t yet have the blueprint for exactly which good bacteria a robust gut needs, but we do know it’s important for a healthy microbiome to have a variety of bacterial species,” she adds. “Maintaining a good balanced relationship with them is to our advantage.”

Gut bacteria breaks down food the body can’t digest, produces important nutrients, regulates the immune system and protects our bodies from harmful germs.

Though multiple factors affect our microbiome – the environment, medications and even whether or not we were birthed vaginally or through a C-section – the food we eat is one of the most powerful allies for the microbiome.

“Diet is emerging as one of the leading influences on the health of our guts,” Ravella adds. “While we can’t control all these factors, we can manipulate the balance of our microbes by paying attention to what we eat.”

In addition to fermented food and drink, fiber is also key. Dietary fiber in foods like fruit, vegetables, nuts, legumes and whole grain are scientifically proven to colonize the gut.

“While we’re only beginning to understand the vast wilderness inside our guts, we already have a glimpse of how crucial our microbiomes are for digestive health,” Ravella says. “We have the power to fire up the bacteria in our bellies.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Fermenting Techniques of Three Northern California Sauerkraut Makers Highlighted

Who is enjoying some sauerkraut at their July 4th BBQs? Pacific Sun magazine featured three Northern California sauerkraut makers — Sonoma Brinery, Wildbrine and Wild West Ferments. The article highlights the different fermenting techniques of the three brands and features this fascinating insight from David Ehreth, president and managing partner at Sonoma Brinery:

“If I can go nerd on you for a moment,” Ehreth warns, before diving into a synopsis about the lactobacillus bacteria that exist on the surface of all fresh vegetables. “You can’t remove them by washing.” What’s more, they immediately begin to feed and reproduce — but not in a bad way, unless they’re a bad actor, he insists.

“Those bacteria will really stake out their turf,” says Ehreth. “They’re very territorial. They go to war with each other.” The incredible part of it is that the four horsemen of the food industry — listeria, E. Coli, botulinum, and salmonella—are on lactobacilli’s hit list. None survive. Five bacteria enter — one bacterium leaves.

Quoting the Food and Drug Administration, Ehreth states, “There has been no documented transmission of pathogens by fermented vegetables.”

Read more (Pacific Sun)

- Published in Science