Fermented Food Waste Increases Crop Growth

Scientists have found a sustainable solution for dealing with both food waste and soil health. They’ve discovered fermented food waste boosts bacteria that increases crop growth, makes plants more resistant to pathogens and reduces carbon emissions from farming.

“Beneficial microbes increased dramatically when we added fermented food waste to plant growing systems,” said Deborah Pagliaccia, the microbiologist who led the research at University of California Riverside (UCR). “When there are enough of these good bacteria, they produce antimicrobial compounds and metabolites that help plants grow better and faster.”

The UCR research team used two types of fermented byproducts: beer mash (byproduct of beer production) and food waste discarded by grocery stores; neither tested positive for salmonella or any other pathogenic bacteria.

Read more (Science Daily)

- Published in Science

Pandemic Spurs Fermented Beverages

The coronavirus continues to drive sales of fermented drinks. Lifeway’s kefir, Farmhouse Culture’s kraut juice, Probitat’s fermented planted-based smoothies, Flying Ember’s hard kombucha and Buoy Hydration’s fermented drinks all report increased sales as consumers take a bigger interest in the immune-enhancing benefits of fermented beverages.

“As demand ramps up for immune-enhancing products, manufacturers have an opportunity to innovate with immune-supporting ingredients and flavors,” says Becca Henrickson, marketing managed of Wixon, a flavor and seasoning company. “When flavoring beverages with immune support ingredients, selecting flavors that increase or complement a product’s health perception is optimal.”

Read more (Food Business News)

New Strains Drive Probiotic Market

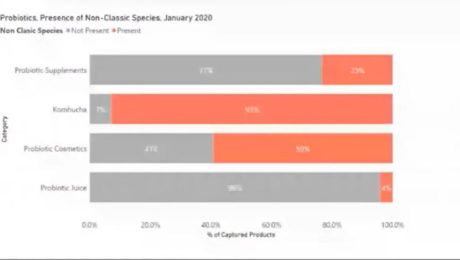

Kombucha and cosmetics are driving growth in the probiotic and prebiotic markets by making products that use non-classic strains of bacteria.

The e-commerce market for probiotic supplements was estimated at $973 million across 20 countries in 2020. America accounts for almost half of those sales. Ewa Hudson, director of insights for Lumina Intelligence, shared this info at the Probiota Americas 2020 Conference. (Lumina and Probiota Americas are parts of William Reed Business Media, the parent company for FoodNavigator.com.) The session, New Horizons for Prebiotics & Probiotics, included Lumina’s insight into non-classic bacteria strains and a panel discussion with leaders in the probiotics field.

In 2020, 32% of all probiotics in America — and 41% of the best-selling ones — contained non-classic species. Hudson said this species classification is a messy space, especially from a consumer’s perspective, because there are so many species. Kombucha includes the most non-classic probiotic species — of those products with probiotics, 93% include non-classic bacteria .

Most products with probiotics include one of the four common bacteria species: lactobacilli, bifidobacterium, bacillus and saccharomyces. Lumina excluded these four from their research to focus on the growth of the non-classic probiotic strains. These include: streptococcus thermophilus, kombucha culture, lactococcus lactis, bifida ferment lysate, enterococcus faecium, streptococcus salivarius, clostridium butyricum and streptococcus faecalis.

Though probiotics are often used in supplements, more fermented food and beverage manufacturers are using probiotic strains in their products, especially in the growing alternative protein market.

Synbiotics are also becoming more widely used; the study found synbiotics were the most prevalent formulate in probiotics. Synbiotics are a combination of both prebiotics and postbiotics. A synbiotic ensures that probiotics will have a food source in the gut.

(Probiotics are live microorganisms, friendly bacteria that provide health benefits. Probiotics can be found in fermented food and taken as supplements. Prebiotics are dietary fibers that feed the probiotics. Postbiotics are an emerging concept in the “biotics” space — postbiotics are the waste byproduct of probiotics.)

“With probiotics, we are really only starting to scratch the surface with the development of synbiotics,” says Jens Walter, PhD, professor of ecology, food and the microbiome at APC Microbiome Ireland.

The new generation of probiotics will depend on strains that are “efficacious in the gut,” Walter noted.

“If you look into the probiotic market, most of the lactobacillus species — and also species like bifidobacterium lactis — are not inherent organisms of the human gut. We’re using a lot of organisms that I would argue have an ecological disadvantage in the gut,” Walter says. “If you’re talking about next generation probiotics, I think what will become is we are looking for the key players in the gut, specifically key players that are underrepresented or linked to certain benefits, and then we are trying to put them back in the ecosystem.”

It’s challenging to find a prebiotic or postbiotic that is precise, he continues.

“Every human has a distinct microbiome. So it’s likely a synbiotic designed for one human may not be as functional in another human,” Walter says. “The opportunities here are tremendous.”

Daniel Ramon Vidal, vice president of research and development and health and wellness at the American food processing company Archer-Daniels-Midland (ADM), also spoke. He noted that the human body is made up of trillions of microbial cells, but we know little about these microbial worlds.

“There is an enormous amount of possibilities to isolate new strains that are living in our body,” Daniels says. “We need as much science as possible, that’s my message”

The panel agreed that postbiotics has become one of the next great concepts that scientists, manufacturers and gastroenterologists have latched onto. But consumers are not as familiar with postbiotics as they are with probiotics and prebiotics , notes Justin Green, PhD, director of scientific affairs for EpiCor, a postbiotic ingredient produced by Cargill.

“This causes more confusion, so I think that’s going to be another interesting aspect of postbiotics — both the identity of what postbiotics are and how it confers its benefits and (how that will be) communicated to the consumer,” Green says.

The New Taxonomy of Lactobacillus

Over several decades, the genus Lactobacillus became unmanageable, encompassing 262 species. Rudimentary research tools lumped any newly-discovered bacteria into the genus, making the taxonomy “very screwed up.”

“The lactobacillus taxonomy became a stack of dirty dishes — everyone knew somebody should do it, anyone could have done it, but nobody did it,” says Michael Gänzle, PhD, professor and Canada Research Chair in Food Microbiology and Probiotics at the University of Alberta. He spoke at a TFA webinar The New Taxonomy of Lactobacillus. “It has become very obvious that the genus is too diverse to group all or the organisms into a single genus. …We need taxonomy to actually describe which group of organisms they mean because if you say lactobacillus in the old sense, we mean a group of organisms that is so diverse that using the same genus name doesn’t make too much sense.”

The lactobacillus genus is large, regulated in many countries and economically important. Gänzle is one of 15 scientists involved in a year-long project using sophisticated DNA tools to analyze the new taxonomy. Findings’ published in the April issue of the Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, spread the species over 26 genera, including 23 new (novel) ones.

“The new taxonomy of lactobacilli means taxonomists have to navigate 23 new names, but maybe I can convince you that renaming the taxonomy is also the best thing since the invention of sliced bread because it does facilitate the communication on all things which relate to lactobacilli,” Gänzle says. He referred to the completed taxonomy as the “lactobacillus monster” because it covers 77 pages.

Despite its heft, he’s proud of the completed project, which reclassifies the genus into relevant groups. “It makes it easier to identify cultures of food applications,” Gänzle says. The group of authors also developed an online tool that makes it easy to look up old names and new names, and provides reference to (genome) sequence data at lactobacillus.ualberta.ca or lactobacillus.uantwerpen.be.

Ben Wolfe, PhD, Associate Professor at Tufts University, moderated the webinar. Wolfe studies the ecology and evolution of microbiomes in his lab (and is a TFA Advisory Board member).“It’s really great to see this community coming around this very important problem,” Wolfe says. “This really helps clarify a lot of things for us.

For the average artisanal fermented food producer, not much will change with the new taxonomy. Producers of traditionally fermented foods don’t put the organisms in their food or drink on their labels — it’s the companies selling starter cultures.

“For someone who doesn’t buy and sell cultures, this doesn’t change,” Gänzle adds. “There will be a transition period until everyone is familiar with the names and putting them on the label. Most, if not all, can still be abbreviated with L.”

- Published in Science

Prospects For Health-Promoting Pickled Vegetables

There are thousands of molecules in the food we eat, but most have yet to be identified. This is especially true in the world of fermentation.

“Lactic acid is not the only byproduct of lactic acid fermentation,” says Suzanne Johanningsmeier, a research food technologist with USDA-ARS. During a TFA webinar, Johanningsmeier presented her research into health-promoting pickled vegetables. “There could be hundreds or thousands of byproducts of this lactic fermentation. As an analytical chemist and someone who is very interested in the composition of foods, I find that fascinating and exciting and a world to explore.”

Johanningsmeier, a leading expert on the chemical and sensory properties of fermented food and veggies, notes that fermentation is a trending food technique. Consumers today want food that is plant-based, enhances gut health, introduces new flavors, made with simple labels and returns to tradition.

“All these things have aligned and intersected for a fermented foods megatrend. It’s exciting to see so much momentum in the Americas rolling for fermented foods,” she says. “All of these trends are based on the belief that these are health promoting foods for consumption.”

The USDA-ARS office in North Carolina State University is staffed by five research scientists, and there are an additional 2,000 more affiliated scientists across the country. Their mission is to deliver scientific solutions to national and global agricultural challenges.

“My long-term goal is to develop science-based technologies that enable the sustainable preservation of fruits and vegetables for production of high-quality, health-promoting consumer products,” Johanningsmeier says.

The most recent USDA-ARS study explored the potential health benefits of fermented cucumbers. Cucumbers are one of the top five vegetables preserved in the U.S. but the only one that’s not canned or frozen. The USDA-ARS found that fermented and pickled cucumbers include many beneficial by-products, including proline, bioactive peptides and GABA (Gamma-Aminobutyric acid, which works as a neurotransmitter in the brain).

“Food processing has a negative connotation. But, actually, fermentation is processing and, as you can see, processing can be good. Processing can add things and certainly make food available to people year round,” Johanningsmeier says. “I think the idea here is how do we preserve [food] so we retain or enhance those inherent, health-promoting properties? The abilities we have now to more comprehensively look at composition are going to help us understand that in the future.”

Maria Marco, professor of food science and technology at University of California, Davis (and TFA Advisory Board member), moderated the discussion. Marco praised Johanningsmeier’s use of analytical techniques to implement fermentation technologies.

“These are exciting compounds, and we know that they have neuroreactive properties or antihypertensive properties,” Marco says.

- Published in Health

How Kefir Affects Gut-Brain Connection

A new study shows kefir affects the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Researchers at APC Microbiome Ireland SFI Research Centre at University College Cork and Teagasc published their results in the journal Microbiome. They found that feeding mice kefir reduced stress-induced hormone signaling, reward-seeking and repetitive behavior. Interestingly, different types of kefir affected mice behavior and changed the abundance of gut bacteria. The researchers concluded that kefir should be studied as a dairy intervention to improve the mood and behavior in humans.

Read more (APC)

“You are what your bacteria eat.”

“Backslop Romance” — Inoculation, Not Contamination

By: Marina Jade Phillips, Trellis & Co.

The first two months of 2018 marked both my first trip to Mexico and my first bicycle tour. Living on two wheels did not slow my fermentation habit; I toted stainless steel jars of fermented vegetables in my panniers. I credit consuming lacto-bacteria with my lack of stomach troubles that can plague travelers in South America. Regularly introducing healthy bacteria into our digestive tract is a great way of inoculating our body with microbes that are on our team. The amount of attention probiotics have received in recent years is long overdue. Traditional cultures have known about the delicious and health-promoting qualities of fermented foods for hundreds of years, even before it was scientifically proven.

Backslop is Such Beautiful Word

Contamination and inoculation are two sides of the same food processing coin: the impact of a small quantity of the right or wrong material can be drastic. The former is the stuff of nightmares for food companies forced to recall tainted products, and suffering travelers perched atop or hunched over a toilet. The latter is how fermented flavors have been passed down through time, sometimes across generations, from one bottle, crock, or barrel to the next. Inoculation is so ubiquitous to the craft that traditional sausage makers gave it a name: backslop.

Backslop, unsavory as it may sound, simply refers to the practice of saving a bit of the last successful batch and incorporating it into the new one, ensuring a small number of the micro-organisms that populated the previous batch will go forth and multiply. There are several reasons why this technique is valuable to both professionals and home cooks. Foremost, the time required for complete fermentation decreases dramatically. A new jar of sliced cabbage or jug of fresh squeezed fruit juice is teeming with all kinds of bacteria and yeast, some of which will produce the desired results, and some of which will produce something inedible.

By introducing a healthy colony early in the process, desirable microbes get a head start and usually out compete less desirable ones in the race to inhabit a new environment. If those microbes have a particularly unique characteristic (champagne yeast produces more carbon dioxide than other wine yeasts, for instance), that character can be reproduced, sometimes leading to outstanding strains by which certain makers and regions become famous.

A 5-Year Love Affair

In more humble corners of the globe, far from French vineyards, I once had a relationship with a sourdough starter that lasted five years.

A sourdough culture becomes more complex with age, and as time went by she (yes, she—around her first birthday I named her Henrietta) developed her own unique flavor. One morning, I came into my kitchen and saw Henrietta’s container on the floor, licked almost all the way clean. A dog had gotten up on the counter, somehow removed the lid, and all but devoured my precious bread making ally. I scraped the dried crust of starter that remained from the edges of the bowl and rehydrated it with water.

Over the next few days I added a bit more flour and water at regular intervals, and in less than a week my robust friend was back in action. I could have sighed, cursed dogs under my breath, and made a new starter, but I was attached to Henrietta, and thrilled to revive her with such little material.

The beginning fermenter has a few options for ensuring success. Of course, there is always the option of simply hoping for the best. Usually, if the food to be fermented is fresh and healthy and the containers and hands in contact with it are clean, odds are in our favor that the microbes that make things sour and bubbly are going to win. However, a splash of the liquid floating around the top of high-quality yogurt (look for something with “active cultures”) will introduce a bit of the right bacteria and speed the process along. A small slosh of juice from a thoroughly fermented sauerkraut or brined vegetable jar will help get the next one going.

Those interested in experimenting with fermented dough will be delighted to know that a sourdough starter is incredibly easy to make: stir equal parts flour and water every day until it smells sour. Wild yeast lands on top of the mixture and is incorporated with every stirring.

Aid this process by dropping an unwashed and unsprayed berry (grapes work best) into the mixture for a couple of days (retrieve the berry before it starts breaking down). Yeast which covers the skins of all fruits will slough off and populate the latent starter. To keep this culture thriving, the sourdough baker saves a small amount of the starter and adds to it more flour and water. Starters exist that are rumored to be hundreds of years old, passed down in just this way.

Practice Safe Fermenting

Interestingly, foods that are not fermented are more prone to contamination from bacteria that can make us very ill, and in the worst cases, kill us. The culprits in large and small-scale food poisonings are often raw and unfermented vegetables. By fostering beneficial bacteria in a salty and acidic environment, we can safely enjoy raw vegetables with all their fiber and nutrient content without the risk of ingesting pathogens.

About Trellis & Co.: We started as a family business created by a bioengineer living on a homestead in one of the remotest areas in the Lower 48. When “running to the store” is a 4-hour drive, every purchase must be a robust and functional investment. Here at Trellis + Co. we design products worth investing in.

Our lifestyle inspired our line of garden-to-table kitchen tools. As gardeners, cooks, and canners, we develop creative solutions to our own kitchen conundrums and pass on that wisdom to you. Also, since we’re kind of obsessed with the planet, our products are designed to last a lifetime — keeping money in your pocket and garbage out of landfills.

- Published in Food & Flavor

Brewers Using Yeast Strains Now for Bold Flavor

Hops used to be the biggest thing in beer to create a powerful flavor — now it’s yeast strains. Brewers are using yeast strains from around the globe for the best flavor.

According to the New York Times: “For some time, it’s been a hopped-up arms race as breweries regularly double or triple the amount of hops to create stronger aromas. With breweries using the same hops, many beers are starting to smell alike. … In search of distinct aromas, brewers are embracing yeast and bacteria strains from across the globe. They’re creating beers that let each type of microbe speak its unique language, and drinkers are listening.”

DeWayne Schaaf, owner of @ebbandflowfermentations Ebb & Flow Fermentations brewery in Missouri, calls himself a “yeast nerd.” He does not use commercial yeasts in his drinks, instead fermenting with yeast strains from Scandinavian farms, bottles of Spanish natural wine and Colorado dandelions. Few hops are required in his drinks as, during fermentation, the yeast converts sugars into alcohol for the flavors.

Other fermenters featured in the article include: @omegayeast Omega Yeast (supplier of yeast strains in Chicago), Berg’n (a beer hall in New York), @alvaradostreetbrewery Alvarado Street Brewery (brewery in California), @yeastofeden Yeast of Eden (brew pub in California), @bootlegbiology Bootleg Biology (yeast lab in Tennessee), @whitelabsyeast White Labs (yeast supplier in North Carolina and California) and Lars Marius Garshol (Norwegian author of “Historical Brewing Techniques: The Lost Art of Farmhouse Brewing

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Fermented Sichuan Pickle Bacteria Reduce Cavities

Researchers in China found probiotics from lactobacilli bacteria in traditional Chinese pickles prevent dental cavities. The study, published in the journal “Frontiers in Microbiology,” evaluated 14 different types of Sichuan pickles from southwest China. Of the 14 pickles, 54 Lactobacilli strains were detected. But only one (plantarum K41) was found to significantly reduce “the incidence and severity of cavities.” The strain reduced the cavity-causing Streptococcus mutans bacteria by 98.4%. The S. mutans bacteria is found in plaque on human teeth.

According to the study: “Pickles are an integral part of the diet in the southwest of China. When fruits and vegetables are fermented, healthy bacteria break down the natural sugars. These bacteria, also known as probiotics, not only preserve foods but offer numerous benefits, including immune system regulation, stabilization of the intestinal microbiota, reducing cholesterol levels, and now inhibiting tooth decay.”

Read more (Science Daily)