Best Practices for Cash Flow Management

Running a food or drink business is challenging in today’s market — there’s increasing competition, fast-paced trends and challenging access to retailers. If you run a fermentation-based business with a long production cycle, those market forces are compounded.

“A lot of businesses in this sector are in it because of the passion, they love what they’re doing, and sometimes the finances can feel very mysterious, there’s an aversion to dealing with it, and they aren’t taking the time to really look and understand the numbers,” says Maria Pearman, a principal with Perkins & Co., Portland, OR-based professionals in food and beverage finance and accounting. She shared her expertise during a TFA webinar, Best Practices for Cash Flow Management.

“Cash flow forecasting, it’s not rocket science. It’s not hard stuff. It is just very foreign to a lot of people and they avoid it,” Pearman says.

Matt Hately, a TFA Advisory Board member who moderated the webinar, agreed. Hately is an investor and advisor in fermented food and beverage brands.

“Managing cash…I would argue that it’s even more of a challenge for fermentation companies where your production cycles aren’t instant, they might take a week or three weeks or six weeks and, when you’re starting, your suppliers are probably demanding to be paid up front, your customers want 30-day terms,” he says .

Fermented Financials

Pearman, author of the book Small Brewery Finance, shared an overview on cash management. Fermentation businesses need to closely manage their cash conversion cycle as production cycles lengthen. The cash flow conversion cycle is the period between when money is spent to purchase ingredients to when payment is received from the sale of the final product.

Fermented products — which can take anywhere from a few weeks to even years to ferment — have a long cycle.

Pearman shared the example of a whisky distiller. After fermentation, whisky ages in barrels for years. All the while — before the product is ever sold — there are ongoing overhead costs for the distillery, like rent, utilities and staff.

“The rhythm of your cash flow is not going to match the rhythm of your income, and cash flow management is about bridging that gap,” Pearman says.

Cash Flow Forecasting

There are three primary financial reports that make up a business’ financial statements:

- Balance sheet (snapshot of the status of a company at a moment in time)

- Income statement (performance over a period of time)

- Statements of cash flows (sources and uses of cash over a period of time)

Often overlooked is cash flow forecasting, the expected inflow and outflow of cash over future periods.

The cash flow forecast, Pearman notes, is not standard in business financial records. It is usually kept outside of an accounting system as it’s information management generally uses. It’s important because a business can’t rely on just their income statement or bank balance to manage cash flow — labor, overhead and cost of inventory must be part of the expenses. She compared managing cash without a cash flow forecast to “building a house without a hammer.”

“One of the biggest pitfalls that I see with businesses is chasing profitability instead of cash flow,” Pearman says. “It is completely understandable because we’re all hardwired to try to do things as efficiently as we can, get the best deal, but truly in the early stages of a company, it’s way more important to manage cash flow than profitability.”

“It’s a high cost for bringing a new product to market. Cash flow issues are going to be prevalent regardless of where you are in your life cycle, and the best way to guard against cash issues is to have a cash flow forecast.”

During the webinar, Pearman shared a detailed look at a sample business’ financial workbook. She noted that it seems arduous to manage that level of detail but, without it, “you’re really flying blind.”

“It will force you to be highly in tune with the rhythms of your business,” she continues. “It will force you to learn it at such a level that it starts to become innate knowledge, you know it like the back of your hand and there’s no shortcut to that.”

View Pearman’s video presentation, companion presentation and companion spreadsheet.

- Published in Business

Sake Brewers Suffer in Japan

As Covid-19 restrictions are lifted, American sake breweries are opening their doors to customers again. But across the world in Japan, where sake originated, many izakaya or sake pubs remain closed. Japanese brewers expect sales to slump for a second year in a row because of the pandemic.

“This right now might be the most challenging time for the industry,” says Yuichiro Tanaka, president of Rihaku Sake Brewing. “There’s nothing much we can do about that. In our company, we’re trying to become more efficient and streamline our processes so that once the world economy returns to what it formerly was, we’ll be able to much more efficiently fill orders.”

Tanaka, Miho Imada (president and head brewer of Imada Sake Brewing) and Brian Polen (co-founder and president of Brooklyn Kura) spoke in an online panel discussion Brewers Share Their Insider Stories, part of the Japan Society’s annual sake event. John Gauntner, a sake expert and educator, moderated the discussion and translated for Tanaka and Imada, who both gave their remarks in Japanese. (Pictured from left to right: Gautner, Tanaka, Imada and Polen.)

Recovery Struggles

Japan — which has been slow to vaccinate (only 9% of the population has been fully vaccinated, compared to 47% in the United States) — is currently in a third state of emergency. In the country’s large cities, no alcohol can be served in restaurants. “This is just devastating to the industry,” says Gaunter.

Though sake pubs in smaller metropolitan areas and countryside regions are allowed to be open, few people are out drinking. Many pubs have closed, and others refuse entry to anyone from outside of their prefecture.

“Sales of sake are very seriously affected,” says Imada, one of few female tôji or master brewers. “Rice farmers that grow sake rice are seriously affected as well. If brewers can’t sell sake, they have no empty tanks in which to make sake, so they don’t order any rice and the effects are transmitted down to rice farmers.”

Sake rice is more challenging to grow than table rice because the rice grains must be longer. The amount of sake rice planted in Hiroshima — where Imada Sake Brewing is based — is down 30-40%. Farmers may give up growing sake rice and switch to table rice for good.

The effects of Covid-19 on Japan’s sake brewers will linger into the fall when the next brewing season starts again.

“We cannot really expect a recovery in the amount of sake produced next season, and so therefore production will drop for two years in a row,” she says.

Premium sake brewers with rich generational historys — like Imada Sake Brewing and Rihaku Sake Brewing — are struggling to sell their high-end products.. Department store in-store tastings — a boon to premium sake brewers — have disappeared.

Adapting to Covid

In New York, as pandemic recovery efforts continue, Polen has seen the pent-up demand from consumers. Brooklyn Kura’s retail, on-premise and taproom sales are increasing. After scaling back production and their team in 2020, Brooklyn Kura is now hiring again.

“More importantly, and I think the silver lining out of this, we really needed to redouble our efforts to create a direct line of communication with our best customers,” Polen says.

During the pandemic, Brooklyn Kura launched both a direct-to-consumer business and a subscription service featuring limited-run sakes. “That’s helped us on our road to recovery.”

Imada Sake, too, found ways to improve business. They’re selling bottles and hosting tasting events through their website.

“One of the principles of the Hiroshima Tôji Guild [guild of master sake brewers], the expression is ‘Try 100 things and try them 1,000 times.’ Or in other words the point is keep trying new things and see what contributes towards improvement,” Imada says. “These words convey the spirit of using skill and technique or technology to get beyond difficulties.”

Imada Sake exports 20% of its production; as more countries recover, exports continue to grow. Direct-to-consumer sales, she says, vary and are only constant around Christmas.

Rihaku Sake sells much of their sake to distributors and is seeing international exports increase. They also began direct-to-consumer internet sales, but that channel “didn’t grow as much as I was hoping.”

Consumer Education

France and Italy export billions of dollars of wine a year. Polen argues that sake could be an equally profitable export for Japan. Education and exposure, he says, are the challenge.

“In craft beer and fine wine, a lot of those initial encounters with those products come in places like the tap room in Brooklyn or the wineries in California or the local craft brewery, so creating more of those connection points and initial introduction points in a market like the U.S., having a better facility to distribute sake across the U.S., will help to expand the market, not just to domestic producers but also for the storied producers of Japan as well,” Polen says.

Sake is the national beverage of Japan, and strict brewing laws strive to keep it pure. Japanese sake can only be made with koji and steamed rice. Add hops to it and the drink cannot be called sake legally anymore.

Many sake tôji in Japan are running a multi-generational family brewery.“These craftsmen, who have been brewing sake since they were young, have decades of experience to develop what we call keiken to chokkan or experience and intuition,” Tanaka says, adding that Japan is the only place to buy certain industrial-sized sake making machines such as steamers and pressers. “There’s a lot of advantages that breweries in Japan have. If brewers overseas get too good, this might actually cause problems for brewers in Japan. However, more important than that, I think it’s important for all of us to continue to study how to make better and better sake so everyone around the world can enjoy it.”

Rihaku tries to make their sake recognizable to local consumers who are unfamiliar with the rice wine. Their Junmai Ginjo sake has the nickname “Wandering Poet,” a reference to the famous poet Li Po. Legend says Li Po drank a bottle of sake then wrote 1,000 poems.

“We think a lot about how to get more people that are non-Japanese and outside of the Japanese context excited about sake making and excited about the sake we make,” Polen says. “That includes those folks that are passionate fermenters, like the beer community, that really want to know and learn about things like spontaneous fermentation. So (sake) styles, like yamahai and kimoto, are very easy transition points, very easy talking points for us with that community of brewers and consumers that are really excited to drill deeper into fermentation, especially natural fermentation.”

- Published in Business

Advances in Yeast

We’re in the midst of a yeast revolution, as genome sequencing creates opportunity for cutting-edge advances in fermented foods and drinks. Yeast will be at the forefront of innovation in fermentation, for new flavors, better quality and more sustainability.

“Understanding and respecting tradition is a key part of this. These practices have been tested for hundreds and thousands of years and they cannot be dismissed. There’s a lot the science can learn from tradition,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University (and TFA Advisory Board member), during a TFA webinar, Advances in Yeast.

Preiss continues: “There’s still a place for innovation, despite such a long history of tradition with fermentation. A lot of the key advances in science are literally a result of people trying to make fermentation better.”

Wolfe, who uses fermented foods and other microbial communities to study microbiomes in his lab at Tufts, said “there’s this tradition versus technology conflict that can emerge.”

“I tell my students when I teach microbiology that much of the history of microbiology is food microbiology, it is actually food microbes, and they really drove the innovation of the field so it really all comes back to food and fermentation,” Wolfe says.

The technology relating to the yeasts used in fermentation has expanded enormously over the last decade, due heavily to advances in genome sequencing. Studying genetics allows labs like the ones Priess and Wolfe run to find the genetic blueprint of an organism and apply it to yeast. Drilling down further, they can tie genotype to phenotype to determine characteristics of a yeast strain. This rapidly expanding technology will disrupt and advance fermentation.

Priess predicted three areas of development for yeast fermentation in the coming years:

- Novelty Strains

Consumers have accelerated their acceptance of e-commerce during the Covid-19 pandemic and they’ll do the same for biotechnology, Priess says.

“Our industry does thrive on novelty,” he adds, noting there are beer brands already creating drinks with GMO yeast. “Craft beer is going to be the first food space where the use of GMOs is widespread — we’re seeing that play out a lot faster than I ever thought it would be with some of these products already on the market. Novelty does have value.”

Wolfe noted many consumers shudder at the idea of a GMO food or beverage, but microbes in beer are dead. Consumers are not drinking a living GMO in beer.

Yeasts also already pick up new genetic material naturally, through a process called gene transfer.

“It’s part of the evolutionary process that all microbes go through,” Wolfe says. “From my own lab and from other labs, cheese and sauerkraut and all these other fermented foods are showing so much genetic exchange that’s already happening.”

- Climate Change

The food industry must address growing concerns about climate change. Priess predicts breeding plants — like barley, hops and grapes — that are more drought-tolerant, or even using yeast technologies to increase yields or the rate of fermentation.

“Craft beer is massively wasteful,” Priess says. It takes between three to seven barrels of water to make one barrel of beer. “It is something we’re going to have to reckon with the next 10 years.”

Yogurt and cheese, too, produce large amounts of waste products.

- Ease of Genomics

The cost and time of genome sequencing has reduced significantly. It used to cost thousands of dollars and take many weeks to document a yeast genome. Now, it can be done for $200 in only a few days.

“The tools to deal with the data and get some meaning from it have never been more accessible. It’s incredibly powerful,” Priess says. “We’re developing solutions for products without millions of dollars.”

Priess does not agree with companies patenting yeasts, “it’s murky territory.” He believes fermentation and science should be about collaboration, not ownership and protection.

“Working with brewers and other fermentation enthusiasts, it’s this incredibly open and collaborative space compared to a lot of the industries,” he says. “I think that’s like our secret weapon or our secret value is that fermentation is so open in terms of access to knowledge as well as in terms of people being willing to experiment and try new things. That’s how it’s able to develop so quickly.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Diversifying the Spirits Industry

The fast-growing, Tennessee-based whiskey brand Uncle Nearest, run by Fawn Weaver (pictured), has created a $50 million investment fund aimed at helping minority-owned spirits businesses.. Black-owned spirits brands are prioritized for investment dollars, followed by those with a founder who is female and/or a person of color.

“I am looking for the brands that have the ability to be the next Uncle Nearest,” Weaver said. “What that means to me is, they are not building to flip, they’re not building to sell. They’re building to create generational wealth.”

When Weaver began Uncle Nearest and wanted to consult with a Black master distiller, she found “the overwhelming whiteness of the world of American spirits.” Her whiskey brand is named after an expert distiller named Nathan “Nearest” Green, who was born into slavery and mentored a young Jack Daniel. Last summer, Uncle Nearest and Jack Daniel’s started a $5 million initiative to bring more Black entrepreneurs into distilling. The response was so great that Uncle Nearest began its own initiative. It’s called Black Business Booster, with the intent to help 16 companies.

“It’s not that people of color don’t have an interest. It’s that we find that they have no path of entry into the industry, no connections where others may,” says Margie A.S. Lehrman, the chief executive of the American Craft Spirits Association. “It’s a very, very tough industry to break into, and if you’re a woman or a person of color, it’s even harder.”

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Business

Artisanal Agave Spirits

Agave spirits are quickly becoming sought-after alcoholic beverages. Hearty desert plants, agaves spend years or even decades developing indigestible carbohydrates that can be hydrolyzed for fermentation, resulting in spirits like mezcal.

“We’re at a golden age of agave spirits right now,” says Lou Bank, cohost of the Agave Road Trip podcast. Bank and cohost Chava Periban shared the centuries-old fermentation processes used to create mezcal in the TFA webinar Artisanal Agave Spirits.

Adds Periban: “The beautiful thing about mezcal is we want diversity and you can use any agave under the sun to be able to make mezcal, which makes this category probably the most intensively diverse category in the spirits world.”

Tequila vs. Mezcal

Tequila and mezcal are both spirits distilled from fermented agave. But tequila can be made only from the blue Weber variety of agave and is made by steaming the agave’s heart (pina) in above-ground ovens. Mezcal can be from any of 30 types of agave and is made by cooking the agave in underground pits lined with lava rocks.

As the market for tequila grew, the term “tequila” was declared intellectual property of the Mexican government in 1974. Extensive regulations were established that, among other things, required tequila — formerly considered a regional type of mezcal — to come from only a specified area of Mexico.

Regulations for mezcal weren’t established until 1994, when it received its own Denomination of Origin. Similar to how champagne can only be made in a specific part of France, mezcal can only be made in nine of Mexico’s 32 states.

Periban and Bank point out a major issue with this certification process for mezcal. It ostracizes rural mezcaleros who may not have the money for certification or may not reside within the geographical boundaries.

“A lot of the communities and the traditions that nourish this nostalgia and this beauty of mezcal, they cannot use this word anymore to name their own spirits, the same spirits that they have been producing for centuries in their communities,” Periban says.

Adds Bank: “We love the flavors, but we are very much about preserving the process and in preserving the process, the number one ingredient in the process are the men and women who make the spirits.”

Bank runs a non-profit, SACRED (Saving Agave for Culture, Recreation, Education and Development), that helps improve lives in the rural Mexican communities where heirloom agave spirits are made.

Wild Fermentation of Agave Spirits

Tequila is made similarly to most alcohol — the producer pitches in a yeast to eat the sugar, picking a specific yeast for the desired flavor.

On the other hand, agave spirits such as mezcal and pulque are made in open air fermentation vats. Wild yeasts off nearby fruit trees change the flavor.

Bank estimates only 1 out of every 100 different commercial tequilas is made using pre-industrial, heritage processes. Mezcal, meanwhile, is just the opposite, with 1 in 100 bottles made using commercialized techniques.

“As the world gets more interested (in mezcal), you’re going to see more industrialization and you’re going to see less and less of this beautiful handmade stuff.”

Mezcal’s flavor palate varies by region, the agave type and the processing. Most mezcal is made and sold locally, to neighbors for weddings and religious festivities.

“If you’re making mezcal, you’re not just selling the product. You’re selling the drink that’s going to be part of their most important days of their lives,” Periban says.

Artisanal drinks with natural ingredients are on the rise, especially in America. Mark McTavish, president of 101 Cider House and co-founder & CEO of Pulp Culture (and TFA Advisory Board member), doesn’t see this trend slowing.

Mezcal, he says, will aid growth in the category, as it’s an alcoholic beverage that, instead of chugging, you sip to taste the complexity of the flavors.

“I really love fermentation and what it gives to a beverage, and I think it’s way more than just alcohol,” McTavish says. “There’s just such a richness there to the connection to a sense of place and a people behind it…that’s why fermentation is so beautiful.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Traditional Finnish Sima

On May Day in Finland, Finns toast the start of spring with a traditional fermented drink called sima. Made with water, sugar or honey, lemon and yeast, the non-alcoholic sparkling beverage is enjoyed by adults and kids. And, as foraging continues to boom in Finland, people are adding wild foods and spices to their sima. An article in BBC Travel details the drink’s history and how it took over two centuries for sima to transition from a high society beverage to a traditional drink for the working classes.

“The reach of sima also extends beyond the festivities. Young students learn to ferment sima in schools; restaurants offer sima on their Vappu (May Day) menus alongside herring, potato salad and sweet pastries; and big breweries bottle and sell their own versions of the drink. Each spring, shop shelves fill with varieties of sima, and newspapers review the best brands. Furthermore, artisanal food culture has turned homemade sima into a trend, with creative home brewers experimenting with new flavours ranging from spruce to cucumber to rhubarb.”

Read more (BBC Travel)

- Published in Food & Flavor

“Strategic Rotting”

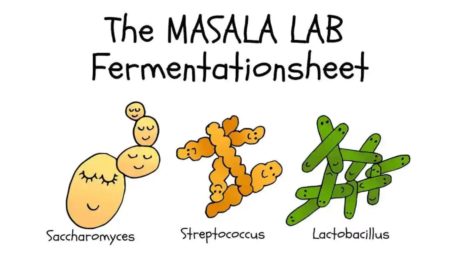

Fermentation saved the human diet, argues Krish Ashok, author of Masala Lab: The Science of Indian Cooking. He calls fermentation strategic rotting. The discovery of fire was key to the human’s survival as they learned to cook meat, but fermentation allowed civilization to create bread and alcohol, turn milk into yogurt and preserve a harvest through the winter.

“Fast forward a few millennia, and we have mastered fermentation to the point where we can pick and choose microbes with precision and generate complex flavours in the bargain,” Ashok writes. Pictured, his charming drawings illustrate microbes used in fermentation.

Read more (Mint Lounge)

- Published in Food & Flavor

A Yeast Primer

Brewers, winemakers and cidermakers are continually on the hunt for the ideal flavor profiles for their fermented beverages. And the key to manipulating those flavors is yeast.

“With beer, you’re taking this kind of gross, bitter soup of sweet barley and hops, and the yeast makes it taste good. Depending on the yeast that gets put in it, it can make it taste like 400 different things, so there’s so much potential there. I think that’s really exciting,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Doug Checknita from Blind Enthusiasm Brewing and Patrick Rue from Erosion Wine Co. to discuss the world of yeast in TFA webinar, A Yeast Primer.

“If you’re invested in vegetable fermentation, yeast might be sort of clouded in mystery and something that is unwanted,” says Matt Hately, TFA advisory board member who moderated the webinar. “It’s what you live by in beverage fermentation in wine and beer and it’s the key to unlocking flavors to make that magic happen.”

Domesticated vs. Wild Yeasts

Just as dogs and cats were domesticated by humans, yeasts have been as well, says Priess, whose company makes and banks yeasts. They are microscopic organisms that adapt, “so if someone’s making beer for over the span of hundreds or thousands of years then the yeast is going to change to kind of get better at fermenting that beer and maybe it’s not going to be so good at surviving out in the wild, just like our toy poodle versus our wolf.”

Other fermented drinks, like wine, sake and cider, use different yeasts with their own specific sets of traits. This is why a wine yeast can’t be used in a beer and vice versa, “though there are some opportunities to experiment.”

Fermenting with wild yeasts has become increasingly in vogue with beer brewers. Aspirational brewers are finding yeasts on the skin of fruit or the bark of trees.

The panelists on the webinar praise experimentation, but note there is risk. Priess says yeasts designed to survive in the wild can be challenging to use in a beer. Checknita points out the safety factor in using yeasts directly from nature as well, “you can get stuff that’s harmful to human health so you have to be careful with your pH levels and what controls there are.”

Traditional winemakers, on the other hand, have long used the wild yeast on grapes to ferment. Rue notes that 10 years ago winemakers began to deviate from this tradition to use pure cultures instead. This process is how many large-scale, industrial producers operate today. But smaller winemakers, who often want to emphasize the specific traits of their terroir, generally use native yeasts and traditional winemaking techniques.

“It’s amazing how wine is how God intended wine to be made because you let nature happen and you’ll probably have a pretty good result with natural fermentation,” Rue continues, “where beer, it’s very touch-and-go, you have to have the perfect conditions and I’ve been able to do spontaneous fermentation with those yeasts.”

The Yeast Family Tree

There’s a large and continually-growing family tree of yeasts, with branches forming for genetic diversity and specialization.

Priess sees three new trends emerging in yeasts: traditional yeasts (like Norwegian kveik) being rediscovered, yeast hybridization (similar to cross-breeding a tomato) and genetic engineering to enhance certain traits of yeast.

“That’s the exciting part of what we’re doing is no one really knows the best approaches to using beer yeast yet, but there’s a lot more new science that’s happening, a lot more brewers that are experimenting, and together we’re collaborating to understand how to work with yeast better and kind of unlock new flavors and new possibilities,” Priess says.

Checknita agrees. He says new yeasts are forming new family trees through spontaneous fermentation, which is taking the base of a beer and experimenting to “push and change those yeasts to do what we want and get that clean flavor that’ll make a beer that tastes good to the human palate.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Reducing Wine’s Alcohol Content

Can you make wine with lower alcohol content? Researchers at Washington State University think so. They are growing wild in a lab to study how the yeasts behave and affect flavor and alcohol levels.

Yeasts used in winemaking — typically Saccharomyces — ferment by consuming the sugars in grapes, producing alcohol. If the grapes have higher sugar levels, they may produce wine with a higher alcohol percentage. But higher alcohol can have a range of negative consequences — bitter taste, incomplete fermentation leaving residual sugar and even higher taxes for the winemaker. WSU researchers hope, by perfecting wild non-Saccharomyces yeast strains, they can help the state’s winemakers better control the fermentation process, and reap the benefits of lower alcohol percentages.

Read more (Daily Evergreen)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Pairing Sake with Food

Does sake go well with Western dishes? Josh Dorcak, chef of Japanese restaurant Mäs, tells Forbes why he thinks sake is an excellent pairing with all food types, maybe even more so than wine.

“Sake pairs with everything,” Dorcak says. “With wine often it seems like there are these rules that one must follow while sake often fits the bill for creative pairings.”

Read more (Forbes)

- Published in Food & Flavor